Articles

The Cambridge Mosque garden, a balm for the soul

Article theme: Al-Andalus, Architecture, Art, Garden, Islam, Landscape, Nature, Quran.

Not only is it the colour of all vegetation, symbolising growth, fertility and hope, but it is also the antithesis of the sandy-browns of the stony desert; a longed-for soothing and gentle relief to the eyes.

Islam was born in the desert: in 6th century Arabia, the Prophet Muhammad was raised among one of the nomadic desert tribes. As far as is known, there is no history of gardens as we understand them in Arabia during this period: a date palm tree and water – the oasis – was a garden.

It was not until Islam conquered other countries with civilisations of their own, particularly Persia, that the Islamic garden may be said to have been born. Islam absorbed the already well-established Persian tradition of royal hunting parks (called pairidaeza in Farsi, from where the English word “paradise” comes) and pleasure gardens and infused them with a whole new spiritual vision.

Thus it could be said that it was the impact of the Islamic revelation on the ancient Sassanid and Achaemenid civilizations of Persia, with their sophisticated irrigation systems, that ultimately brought the Islamic garden into being.

A taste of paradise

My own interest in Islamic gardens began at the Royal College of Art (RCA) in London. I studied under Keith Critchlow who designed all the geometric patterns at the Cambridge Mosque. He was well-known for reviving geometry – one of the principal languages of Islamic design – as a language of metaphysics, popularly known as “sacred geometry”. At the RCA, he introduced me to the profound beauty and meaning of Islamic art.

Through this, I became Muslim myself and eventually was lucky enough to bring together my own love of English gardens with this new love of Islamic spirituality and its civilisation.

In 2011, Timothy Winter, lecturer in Islamic Studies at the University of Cambridge, approached me with the idea of designing the garden for the Cambridge mosque for which he was raising funds.

By this time I had published my book The Art of the Islamic Garden and completed several designs for Islamic inspired gardens, mainly the four-fold type, in Europe and the Gulf.

The Cambridge mosque would be the first in Europe to be constructed according to ecologically friendly principles. Everything from energy use and lighting, to the structural elements, was designed with sustainability in mind.

Winter was keen to create an Islamic garden that would fit into the urban context of Cambridge as well as evoke the atmosphere of peace and contemplation that many gardens of the Muslim world are famed for.

The area I was asked to design was small, lying in between the road and the atrium of the mosque. The inner main garden is the Islamic garden, designed in a space measuring approximately 30m x 10m.

The area I was asked to design was small, lying in between the road and the atrium of the mosque. The inner main garden is the Islamic garden, designed in a space measuring approximately 30m x 10m.

The overall aim was to give a little taste of Jannat al-firdaws, the Gardens of Paradise as described in the Quran, providing as much soft green and planting as possible in the limited space to balance the “hard” materials of the mosque and paving.

Through this, I became Muslim myself and eventually was lucky enough to bring together my own love of English gardens with this new love of Islamic spirituality and its civilisation.

The second aim was not only to offer a contemplative calm space for visitors to walk through or sit in before entering the mosque but also to make an uplifting impact upon the senses, in contrast to the noise and pollution of the street.

Third, myself and my brilliant team from the landscape design studio Urquhart and Hunt, wanted to create something that looked comfortable in an English urban setting whilst also speaking of Islamic design.

Here was an opportunity to demonstrate to the neighbourhood as well as the rest of Cambridge that it was possible to marry eastern design principles with a western context in a pleasing and harmonious way.

What better way of enlightening the UK, a country renowned as a nation of gardeners, about Islam with its belief that paradise – our heavenly home – is a garden?

The elements of the garden

This is not as hard as you might imagine, given that many of the key elements of an Islamic garden are universal. To a certain extent, what applies in Cairo, applies in Cambridge.

The four-fold design – or chahar-bagh (from the Persian meaning “four gardens”) – of the quintessential Islamic garden, is found throughout the world in a multiplicity of forms, not least in Cambridge itself.

Look at the quadrangles of the university colleges: what are they if not four-fold inward-looking gardens? Likewise, mediaeval cathedral cloisters are based on a similar layout, as are many enclosed kitchen gardens.

The traditional architecture of Cambridge, thought of as quintessentially European, actually has profound Islamic echoes.

Enclosure is another key element of the Islamic garden. The original idea was that this would keep the heat and sand of the desert outside while protecting the abundant planting within, creating a calm and peaceful sanctuary.

This notion may be transferred to the urban context, where the aim is to keep the noise and pollution of the city outside while nurturing the tranquil oasis within.

This is not as hard as you might imagine, given that many of the key elements of an Islamic garden are universal. To a certain extent, what applies in Cairo, applies in Cambridge.

The idea of a sanctuary, of an internal garden, is also symbolic. We need to nurture our own internal garden – our heart and soul. As the 13th-century Persian poet Rumi wrote: “The real gardens and flowers are within, in man’s heart, not outside.”

This garden requires nourishing in order to give us some peace from our own endlessly chattering thoughts. In Islam, this is gained through prayer, contemplation and, most of all, through the remembrance of God. For others, it may be through contemplation alone, with the word “contemplation” meaning to gaze attentively upon, and cultivate, a sacred space.

The fundamental archetype of Islam’s four gardens of Paradise is described in the Quran, especially in Surat al-Rahman: “For him who feareth the standing before his Lord there are two gardens… And beside them there are two other gardens.” These four gardens are the source and inspiration of the traditional chahar-bagh design of many Islamic gardens worldwide.

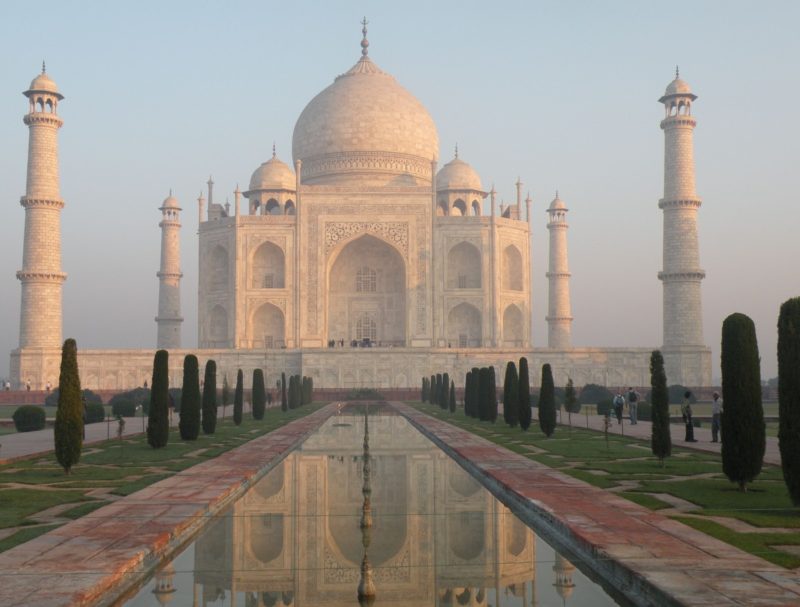

They are given material form, for example, in the exquisite gardens and courtyards of the Alhambra and Generalife in Spain, in the great Mughal mausoleum gardens of India (most notably the Taj Mahal), and the gardens of Iran, such as the Bagh-e-Fin and Chehel Sutun.

There is no doubt, though, that the two supreme elements of the Islamic garden are water and shade. Descriptions in the Quran refer often to fountains and running water. The importance of water is symbolic as well as physical. The eternally-flowing waters of paradise represent the source of all life on Earth, as well as being symbolic of the soul – sometimes restful in a still pool, sometimes dynamic when flowing fast.

More profoundly, in Islam water represents the light of divine knowledge and is regarded by worshippers as a gift and blessing from God, and a sign of his mercy (“We sent down out of heaven water and caused to grow in it of every generous kind”).

In the paradise gardens of the Quran, four rivers flow from the fountains in the centre of each garden.

In earthly gardens, the rivers are often replaced by pathways due to water scarcity, as well as the difficulty and cost of maintenance.

Water and shade are less vital in Cambridge than in hotter climates; nevertheless, despite the cooler conditions, they are still crucial and contribute greatly to the overall tranquillity of the garden there.

Water and shade are less vital in Cambridge than in hotter climates; nevertheless, despite the cooler conditions, they are still crucial and contribute greatly to the overall tranquillity of the garden there.

It was clear from the beginning that the design of the Islamic garden in Cambridge should have a fountain in the centre, around which visitors would walk from the entrance gateway to the mosque. All geometric patterns radiate from the centre of a circle.

The circle is symbolic of the celestial realm and Divine Unity, while the square and the number four represent the material realm.

The Islamic garden will often have a circular fountain in the centre, with the four pathways (or water-rills) radiating outwards to the four directions of space. Thus the garden could be said to be a meeting place between heaven and earth.

In our Cambridge garden, visitors either walk around the circular, scalloped limestone fountain on their way to pray, or sit on the benches listening to the sound and movement of the water.

Here, they can enjoy the shade of the crab-apple trees and the planting in the gardens on either side.

Creating a ‘living jewelled carpet’

On either side of the fountain, to the right and left, we created a small chahar-bagh. The pathways are paved with a cream-coloured Yorkstone and the planting beds are designed with a mixture of plants, scented wherever possible.

There are perennials (such as roses, geraniums and iris), flowering shrubs (including myrtle, jasmine and daphne) and a succession of bulbs, including narcissi and tulip species. Perfume is an important characteristic of an Islamic garden, not only because it is deeply pleasurable, but also because it has the power to evoke profound memories.

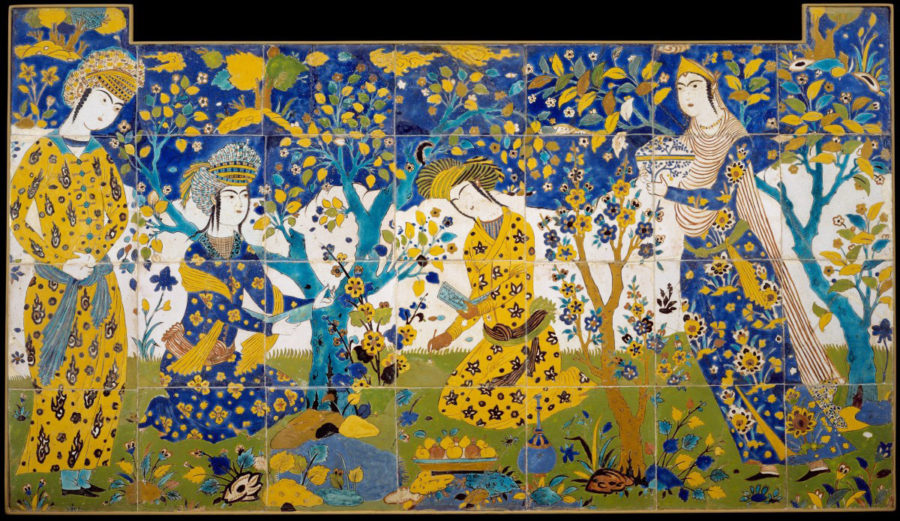

The plant selection balances bold colour amongst plenty of green, to be calm and meditative while giving the sensation of walking through a richly jewelled living carpet. The evergreen geometry of the garden is provided by a dark green yew perimeter hedge against which the colours of the flowers can sing.

Many of the plants have been selected because of their provenance in Turkey, the Mediterranean and further East, while also being able to thrive in the UK. Together with a few select grasses, they have been laid out in a naturalistic style to present a contemporary vision of sustainable, ecologically-friendly planting for the city.

Indeed, a guiding principal has been not only to combine Islamic design with a contemporary British plant palette, but also to select plants which promote biodiversity and encourage pollinators.

Fruit is a key element of the paradise gardens and, after much deliberation, we selected an upright crab-apple tree, one in each of the eight planting beds, aligning them with the “tree-columns” of the mosque atrium directly behind. These crab-apples offer delicate pale-pink spring blossom, then bright scarlet fruit followed by strong autumn colour.

Indeed, a guiding principal has been not only to combine Islamic design with a contemporary British plant palette, but also to select plants which promote biodiversity and encourage pollinators.

Petra Ulrik, landscape architect and a key member of the planting team, remarked on the incredibly positive response from the local community, with passersby even offering to help plant the garden.

‘A balm for the soul’

One year on, the garden is beginning to achieve the result we wanted, a pleasing balance of rigour and abundance that integrates well with the design of the mosque.

We hope that sitting here by the fountain, surrounded by the trees and plants in front of the mosque, will offer not only a balm for the soul but also something uplifting, encouraging visitors to deepen their connection with both the outer natural world and their inner selves.

Before the coronavirus lockdown, Muslims and non-Muslims alike came from far and wide to visit the mosque. We landscapers like to think that the garden is an essential part of the experience, enabling the visitor to slow down and take a moment before either entering the mosque to pray or simply observing the soaring, vault-like architecture within, enhanced by intricate geometric patterns.

“For him who feareth the standing before his Lord there are two gardens… And beside them there are two other gardens.” Quran, Surat Rahman.

It has been said many times that visiting gardens and parks, walking in nature and, better still, gardening itself, offer comfort and healing for the heart and mind. An Islamic garden of the chahar-bagh type, with its emphasis on contemplation and the inward, and its reference to the gardens of paradise, may offer even more in the way of a calming sanctuary.

In the age of coronavirus, many of us are addressing our mortality with a little more seriousness. To sit in a garden consciously inspired by the eternal gardens may offer even more in the way of quiet and peace – remembering also that salaam, or peace, is the only word spoken in the heavenly gardens.

The Art of the Islamic Garden, by Emma Clark, is published by The Crowood Press

Source: middleeasteye.net