Articles

Uzbekistan, Pearl of the Eastern Muslim world

Article author: Iftikhar Gilani (Andalou Agency)

Date of publication of the article: 09/12/2020

Year of publication: 2020

Article theme: Architecture, History, Islam, Tourism.

At the crack of dawn, bright summer sunshine basking the city of Tashkent — the capital of Uzbekistan — is a boon for morning walkers, but a bane for late risers. A sunny morning, as early as 4.30 a.m., forces one to jump out of the bed to enjoy charms and secrets of the fairy city, invigorating with freshness.

The paved lanes of Tashkent, Samarkand, and Bukhara in the Central Asian country of Uzbekistan are lined with mesmerizing details that had once put them on a strategic trajectory astride the old Silk Road. The cross-section linking Anatolia and the Mediterranean Sea with China on one hand, and South Asia with Europe and Africa on the other, made this region a melting pot of civilizations.

The paved lanes of Tashkent, Samarkand, and Bukhara in the Central Asian country of Uzbekistan are lined with mesmerizing details that had once put them on a strategic trajectory astride the old Silk Road.

President of Uzbekistan Shavkat Mirziyoyev is now hoping that China’s Belt and Road initiative, running through his country will bring back this romantic nostalgia and glory to the region. The country is also on way to joining the Turkic Council — an organization that includes Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Turkey — to explore connectivity, common history, language, identity and culture.

Just few centuries ago, when the West was still gasping for enlightenment, many metropoles in the East like Istanbul, Samarkand, Bukhara, Nishapur and scores of others, were frontiers of knowledge and civilization. Istanbul is perhaps the only metropole having succeeded to preserve its character. Others have lost their cultural, commercial and intellectual centrality.

Uzbekistan — a landlocked country in Central Asia, bordering Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Afghanistan — has a striking resemblance with Turkey in the west and to the Valley of Kashmir to its distant east.

A visit to this land will confirm, why Kashmir — currently at the dispute between India and Pakistan — is also more Central Asian than South Asian, taking in view the striking similarities running across the strands of culture, language, architecture, culinary and music.

The 450-kilometer (280-mile) road connecting the modern capital city of Tashkent to the ancient city of Samarkand is lined with Chinars. Roadside highway restaurants serving food on raised wooden platforms — lined with carpets and pillows, instead of tables and chairs, under the shade of chinars and mulberry trees — are spectacular.

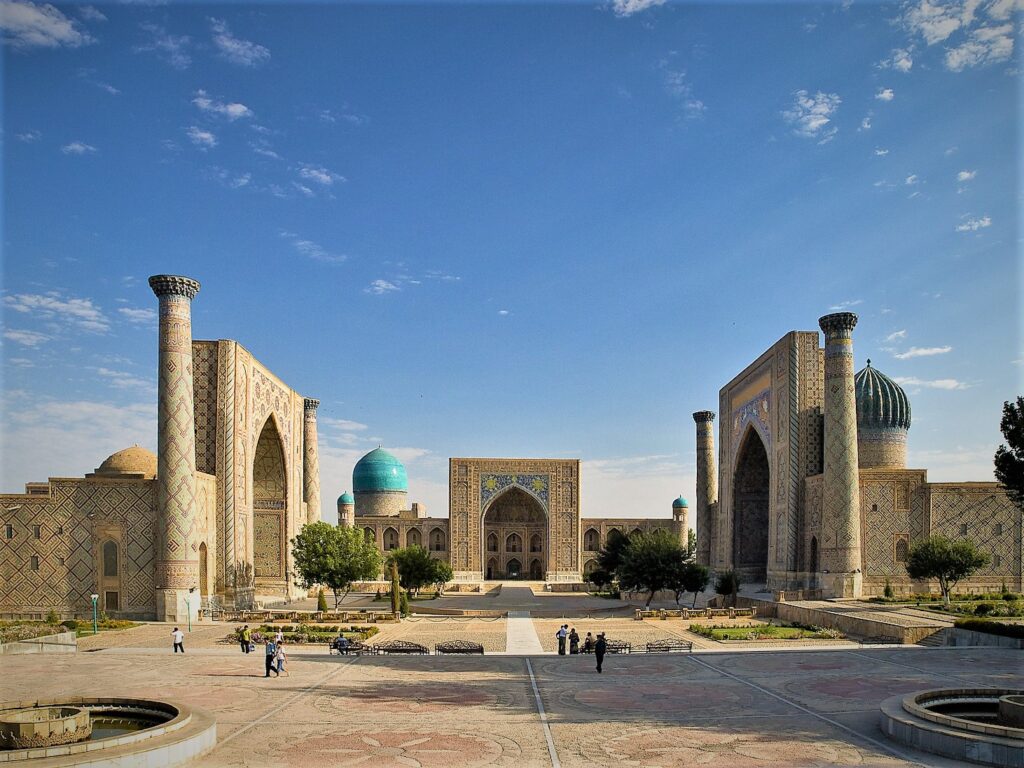

Glittering minarets, voluptuous domes and hypnotic mosaics make Uzbek cities of Samarkand and Bukhara grand live museums.

Central Asia is also home to Sufi saints followed and revered in Kashmir. Mir Syed Ali Hamadani’s grave lies in the Kulub province of Tajikistan.

Central Asia is also home to Sufi saints followed and revered in Kashmir. Mir Syed Ali Hamadani’s grave lies in the Kulub province of Tajikistan. He is credited to bringing Islam to Kashmir, which is perhaps the only region in South Asia, where upper caste Hindus converted to Islam in large numbers.

Another most followed saint, 14th-century Bahauddin Naqshband — founder of Naqshbandi order — is buried in the outskirts of the city of Bukhara.

The cities of Bukhara and Samarkand are dotted with Khanqahs — the spiritual abode of Sufis and dervishes.

Uzbuk Timur Tillyaev, a resident of Bukhara, narrates that till the 19th century, dervishes from Turkey and South Asia would come here, to seek spiritual guidance.

“Our grandfathers would tell us, how excited they used to be at the arrival of dervishes from far-off lands. They would welcome and feel proud to arrange meals for visiting saints,” he said.

After the Soviet invasion, these Khanqahs were locked. The iron curtain put up by the Communist regime snapped ages-old connections and cultural linkages.

Amir Timur, a national hero

The fascinating six-hour drive from Tashkent to Fergana — the only road link that connects the eastern fertile region with the rest of the country is dotted with snow-capped mountain peaks, pine forests. These ingredients resemble to the Srinagar-Jammu highway — the only surface link that connects the Kashmir Valley with India.

In 1526, a young prince Zahiruddin Mohammad Babur from this fertile valley crossed the Pamirs and the Hindukush mountain ranges and came through the Khyber Pass, to knock at the doors of India with just 12,000 loyal men. He established the Mughal Empire in Delhi that ruled large swaths of South Asia, till 1857.

Babur’s ancestor Amir Timur has been iconized by the Uzbekistan government as the national hero. The capital Tashkent’s main streets radiate from Amir Timur square, where the statue of Timur and a museum takes pride of place. The statue of Timur and his horse occupy the center of the capital. The square previously hosted the sculpted image of the first Russian Governor of Tashkent, Konstantin Kaufmann, followed by statues of Lenin, Stalin, and Karl Marx, neatly tracing the rise and fall of personality cults.

Housed in a beautiful round building with a green dome, the museum which looks like a mosque, has a collection of 5,000 artifacts focusing on the genealogy of Amir Timur, his coming to power, military campaigns, diplomatic relations, trade and development.

Earliest written copy of holy Quran

Besides, Chorsu Bazaar — located in the center of the old town under its blue-colored domed building, where all daily necessities are sold — the primary attraction of Tashkent is the library museum at Khast Imom square. It houses the 7th-century copy of the Holy Quran, which the third caliph Hazrat Usman was reading when he was martyred 656.

Dry blood marks are still visible on the pages of the oldest copy of the Holy Quran, written on deer skin. Azmat Akhmetov, a caretaker, perhaps got curious when he found me engrossed looking at the pages. He rushed to ask if I was a Muslim? After I nodded, he shot another question, which sect? Then elaborated, whether I belong to Hanafi sect? “I belong to Hazrat Usman’s sect.” The answer, however, did not satisfy him much, as I saw bewilderment looming large on his face. There was no sectarianism in Islam during Hazrat Usman’s period, I explained.

According to Akhemtov, the rare artifact was brought to Samarkand by Timur, then taken to Moscow by the Russians in 1868. Lenin returned it in 1924 as an act of goodwill towards Turkestan’s Muslims. The museum also houses rare 14th- to 17th-century books, including one thumb-sized Quran in an amulet case.

Memories of India-Pak war and peace

In the heart of Tashkent, the Uzbekistan hotel and the magnificent conference hall across the road recap India-Pakistan peace agreement, brokered by Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin after they fought a war in 1965. The war was an escalation of irregular fighting that started on Kashmir, a sore point between the two countries ever since Partition in 1947.

Hours after signing the agreement, Indian Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri mysteriously died in Tashkent, leading to persistent conspiracy theories. The city hosts his bust and a road named after him.

The difference also arose between Pakistan President Ayub Khan and his Foreign Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in Tashkent itself, soon after signing the agreement. Bhutto parted ways and launched his own party — the Pakistan People’s Party and rose to become prime minister. In India as well, Shastri’s death paved the way for the 48-year old Indira Gandhi, to become the first woman prime minister of India. With a brief interlude of two years, she ruled the country till October 1984 when she was assassinated by her bodyguards. Tashkent, in fact, not only gave South Asia Mughal dynasty, but also two political families — Gandhis and Bhuttos.

Samarkand, pearl of the Eastern Muslim World

While Tashkent is abundant with the remnants of Russian colonization and 75 years of the Soviet communism, cities of Samarkand and Bukhara have shed the yoke. Mosques and mausoleums dot Samarkand, one of the most ancient cities in the world. Pointing towards a hillock of mud and ruins of an old fort, guide Anara said this old city was pulverized by Genghis Khan.

The 2,750-year-old city has witnessed many upheavals. Originally named Afrasiyab, it bears the marks of the conquests of Alexander the Great, Arabs, Genghis-Khan and lastly of Timur, who refurbished the city. Once known as the pearl of the Eastern Muslim World, its geographical position in the Zarafshan valley puts Samarkand to the first place among cities of Central Asia.

Chinese scholar-travelers Faxian and Xuanzang, Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta, and Marco Polo have all written about the city. Surrounded by gardens and orchards, the sweetness of Samarkand fruits has found mention in Ibn Battuta’s travelogues.

The majestic mausoleum of Amir Timur stands tall in the city center. The basement where actual graves lie, is sealed and guarded. Legend goes, that whenever door was opened, tragedy has befallen.

Anara told us that the Russian expeditioners led by Tashmuhammed Kari-Niyazov and Mikhail Gerasimov had opened the tomb in 1941. Local residents and Muslim clergy tried their best to dissuade the excavations, but Russians were unmoved. The remains of Timur and his dynasty were sent to Moscow. Two days later, on the night of June 22, Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union. Three years later, a month before the Battle of Stalingrad, Stalin ordered the return of the remains of Timur and his dynasty to Samarkand. They were buried again with full honors. Soviets won the decisive battle and then continued to march, till they conquered Berlin.

The city is associated with legends like Ibn Sina, a key figure of Islamic philosophy and science, and Mohammed al-Khwarizmi — the father of algebra. Though both of them were born elsewhere in Uzbekistan, the city nurtured them.

Rich with nostalgic details, Alexander the Great found his wife Roxana in Samarkand, whom he described as the most beautiful woman in the world. Also, it inspired American poet Edgar Allen Poe to write his famous poem, Timur, about the sacrifices one must make in life to achieve happiness.

A visit to this city cannot be complete without visiting the heart of the ancient silk route, the Registan Square, a kind of a world trade center of the ancient and medieval world. A real gem, located some 500 yards away from Timur mausoleum, was a resting and trading place for caravans. It was not only goods that were traded here, but philosophies and political thoughts as well. Therefore, the square is surrounded by two grand madrassahs and a mosque. All three erections have their own unique decor. The square was also used to gather people to announce royal decrees. It is also the venue for the Sharq Taronalari, an international festival of traditional music held every year.

Imam Bukhari’s tomb

Pilgrimage tourists could see unique places in Samarkand, a tomb of Prophet Daniel, the Rukhabad Mausoleum (the tomb of Sheikh Burhanuddin Sagardji, the spiritual mentor of Amir Timur), and the Shah-i-Zinda (tomb of Qasim bin Abbas, cousin and companion of the Prophet Muhammad).

In the village Hartang, 25 kilometers from Samarkand, is located one of the most revered pilgrimage sites — the mausoleum of Imam al-Bukhari, a famous theologian and Hadith collector. The mausoleum complex also houses a university, museum, madrassa and a mosque.

Imam Bukhari, or Muhammad ibn Ismail ibn Ibrahim, authored sayings of the Prophet Muhammad, or the Hadith, known as Sahih al-Bukhari after great scrutiny of their sources. The amount of research he went in has made his collection of Hadith most authentic.

In the Soviet period, the mausoleum was locked and forgotten. But in 1954 when Indonesian President Sukarno visited Moscow, he sought permission to visit and pray at the tomb of Imam al-Bukhari. Following Sukarno, another visiting dignitary, President of Somalia Madiba Keith, also sought permission to visit. That apparently led Moscow to restore the mosque and mausoleum, and hand it over to the Spiritual Administration of Muslims of Central Asia and Kazakhstan. In 1998, President of Uzbekistan Islam Karimov built a magnificent memorial complex and declared Imam Bukhari an intellectual guardian of his country. The mausoleum is in the form of a rectangular prism. The dome is double ribbed, decorated with blue tiles. In the center of the courtyard is a pond “Hauz” known to possess medicinal properties.

Uzbekistan is not yet known around the world as a destination for pilgrimage tourism. Surayyo Usmanova, a visiting scholar at George Washington University, says it was high time for the country to promote and link to the world through its rich cultural, historical, and religious heritage.

“The government understands the importance of tourism to economic growth and national prestige and is moving forward decisively with special focus on the Islamic world, and promoting pilgrimage tourism. Whether you are religious or secular, the Great Silk Road beckons,” she said.

Source: Andalou Agency (click here to read full article)