Articles

Muslim women of Castile

Date of publication of the article: 08/12/2020

Year of publication: 2020

Article theme: Al-Andalus, Ethnography, History, Islam, Mujer, Women.

Due to its gender identity and its religious option, the Muslim women of Castile were subordinated first to the Muslim men, and then to a Christian-majority society. As a result, they were ignored almost completely by the historical sources.

This article focuses on the most inaccessible object of study of the Medieval Castilian Islam: the Muslim women of Castile. Due to its gender identity and its religious option, the Muslim women of Castile were subordinated first to the Muslim men, and then to a Christian-majority society. As a result, they were ignored almost completely by the historical sources.

Among the few testimonies that refer to Muslim women are the gradual restrictions to their dress and physical appearance, which were reflected on the legislation at the time. Thus, at least since the reign of Alfonso X (1221-1284), they weren’t allowed to wear red close fitting clothes, nor golden or silk complements.

Since the beginning of the 15th century, as it happened with the Muslim men as well, they had to hang a turquoise half-moon on their right shoulder over their loose clothes. Queen consort Catalina de Lancaster forced them to wear big cloaks that covered them to their feet and that, folded, covered their head and face.

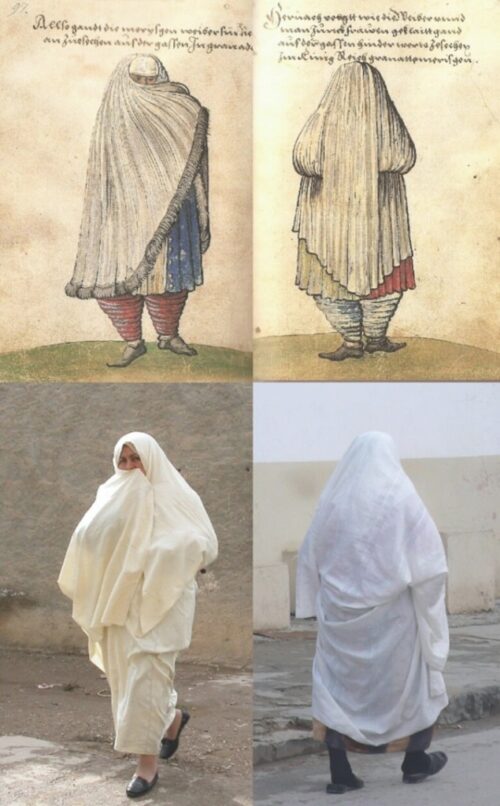

A century later, by the end of the second decade of the 16th century, the Flemish artist Christoph Weiditz joined King Charles V on a trip to the Iberian Peninsula, and portrayed Granada’s Muslim Moorish with big cloaks that covered them completely and prevented them for showing their face. This dress might have been inherited from the clothes impositions forced upon those Muslim women.

Queen consort Catalina de Lancaster forced them to wear big cloaks that covered them to their feet and that, folded, covered their head and face.

The attire reminds of the clothes currently wore by Tunisian women in those towns founded by the Moorish at the beginning of the 17th century, when they were forced into exiled by king Philip III (1578-1621). Tunisia fostered most of the 300,000 expelled Moorish, and the Islamic Hispanic legacy continued through these women, as shown by the preservation of their clothes.

Sources also point out at the interdiction of “Christians and infidels” to marry, and at the judgement of sexual relations between them, with a clear gender bias. While there was an almost total impunity on the relations between Christian men and women belonging to any minority group, the civil-religious law deemed the contact between Muslim or Jewish men with Christian woman punishable by death.

The few references that allow us to approach the autonomous identity of these women mention the “independent” Muslim and Moorish nurses and midwives that worked on Christian environments (not without problems), in activities related to the nurturing and health sectors. Due to their good reputation, there were ecclesiastical condemnations to these professions almost since the beginning. For instance, on the 15th century, the bishop of Sigüenza, Pedro de Luján, forbade Christian children to drink “Moorish milk”.

The few references that allow us to approach the autonomous identity of these women mention the “independent” Muslim and Moorish nurses and midwives that work on Christian environments (not without problems).

Moorish midwives were also highly appreciated at the time, due to their mix of medical knowledge, magic and superstition.

However, from the 15th century on, and due to the growing Christian intolerance towards Islam, their job was prosecuted, forbidden and punished by flagellation. Remarkably, they were always allowed to assist Christian women on “women issues”.

It is also more than likely that they worked helping men on “Moorish professions” such as construction or carpentry.

In addition to these prohibitions imposed from the exterior, the Muslim community also controlled the life of women. We find an example on the document “Breviario Sunní” (Sunni Breviary, also known as the Kitab Segobiano), written in 1462 by the well-known faqih Iça de Yebir, mayor of the Moorish of Castile, in which he subordinated the women to the male figure, be it the father or husband.

“The woman is obliged to serve her husband inside the house, to cook for him and nurse their children, as well as on bed.”

However, there have always been women figures of resistance and leadership. We can point out at the active participation in the socialization of the Muslim community, in circumcisions, weddings, endowment celebrations or funerals. As well as the cases of Muslim women who received the respectful treatment of “Ms.” (doña), when they were the only heiress or widows and heads of their household.

It is also noteworthy the role of certain Muslim women in the late period of the hidden Islam (the end of the Moorish 16th century), which showed the last stronghold of a rich and fruitful historical period that was the Peninsular Islam.

A new reality emerged after the fall of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada (1492) and the disappearance of Islam from the Christian kingdoms, the expelling of the Moorish from Portugal (1947), Castile (1502), Navarra (1515) and Aragon (1525). This new reality was the “cryptoislam”, when the descendants of the last Peninsular Muslims were forcefully baptized, and, under their new adopted Catholicism and their Christian names, they continued practicing and spreading the word of Islam, secretly, to avoid the Inquisition.

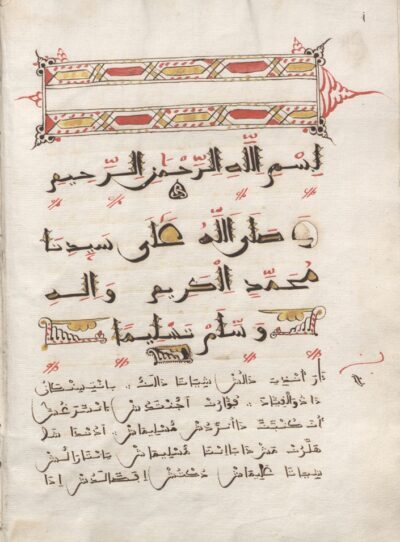

In 1533, a meeting took place in Zaragoza, which gathered many scholars and fuqaha from Castile and Aragon, to discuss and develop a strategy of survival for the Muslim community. Among other things, a young man from Castile, Gutierre Velázquez, was put in charge of developing the principles and norms any Muslim should follow to act in accordance to their faith, in order to serve as a guide to distribute among the Muslim communities. He wrote it in aljamia (Romance language expressed through the Arabic alphabet), and it is known as the Tafsira (Treaty). He signed it under a pseudonym, Mancebo de Arévalo, in order to hide its real identity. The author wrote two other books, Short compendium of our Holy Law and Sunna and the Summary of the spiritual relation and practice, both in aljamia as well. He can be included among the most prominent scholars of the Peninsular Islam, and even one of the most prominent religious authors of the Spanish Golden Age.

But the most interesting point is that Mancebo did not only write the norms and doctrinal principles, but he also described his travels around Spain to search, locate and interview the people that had lived in the times when Islam was allowed, and who could advise him on the writing of an Islamic treaty in accordance with the Maliki school.

Among these people, he interviewed four old women, among which we find the Mora de Úbeda (original from Granada) and Nuzzayta Calderán (probably located in Castile).

His biggest reference was the Mora de Úbeda, which he found following Nuzzayta’s indications. She had been a prominent figure during the last Nasrid times, and she was considered an important commentator of the Quran. She was old, on her 90s, extremely big, so much that the young author continuously refers to it throughout the Tafsira. But the most relevant point is that it shows how these women had still great recognition among the Muslim population, despite its age and physical limitations (she could not leave her house), and that, in spite of their appearance as new Christians, they did not want to lose or forget the essence of the Islamic doctrine and they looked for her for advice.

A young man from Castile, Gutierre Velázquez, was put in charge of developing the principles and norms any Muslim should follow to act in accordance to their faith, which could act as a guide to distribute among the Muslim communities.

Nuzzaiyta, quoted in the three works mentioned, was a “magician” (maybe an astrologist) and a midwife, and she lived in the town of Huerta del Almirante (Cuenca), although she moved constantly to other cities such as Ávila or Segovia, as well as the Barbary Coast and she might have even gone to Mecca. She is a character that Mancebo finds several times on the road and in several cities. It is likely that both met under the disguise of their professions (midwife and muleteer), but carrying out their real proselytism work through their travels. They have a longer encounter of 9 days in the town of San Clemente (Cuenca), where, hidden in an inn, they debate and discuss, and Nuzzaiyta trains Mancebo on the reading of the Quran.

In sum, we see how, during the first quarter of the 16th century, the memory of Islam in the Iberian Peninsula was still alive among certain people, some of them women, who became a reference for those who struggled to keep this religion alive in the new age of the Spanish kingdom, in spite of the growing Christian acculturation, the Inquisition, and the need to survive underground. Although this religion and culture had been deeply rooted in the Iberian Peninsula, at the time it already had its days numbered,

Nuzzayṭa Calderán and the Mora de Úbeda complement each other: the former represents popular religiosity, the later doctrinal religion. Thanks to the works of Mancebo de Arévalo we can present them to the world (there probably were more like them). For their roles as transferors of the Islamic knowledge we should include them among the most prominent contributors to Islam in the Iberian Peninsula, as well as to the Castilian Islam of the 16th century.

Source: Al-Andalus y la Historia

Translation: Alfonso Casani – FUNCI