Articles

The Spread of Islam in Ancient Africa

Article theme: Ethnography, History, Islam.

Article written by Mark Cartwright and originally published in Ancient.eu on May 2019.

Following the conquest of North Africa by Muslim Arabs in the 7th century CE, Islam spread throughout West Africa via merchants, traders, scholars, and missionaries, that is largely through peaceful means whereby African rulers either tolerated the religion or converted to it themselves. In this way, Islam spread across and around the Sahara Desert. In addition, the religion arrived in East Africa when Arab traders crossed the Red Sea and, in a second wave, settled along the Swahili Coast. Military campaigns did occur from the 14th century CE against the Christian kingdoms of Nubia, for example, while in the 18th century CE the Muslim Fulani launched a holy war in the Lake Chad region. There were also sometimes violent resistance by supporters of traditional African beliefs such as animism and fetish, spirit and ancestor worship.

Nevertheless, for at least six centuries Islam spread largely peacefully and gradually wherever there were trade connections with the wider Muslim world of the southern Mediterranean, the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Sea. The religion was not adopted uniformly, and neither did it maintain its purity of origin, very often existing alongside traditional practices and rituals. With the religion came other ideas, too, especially those concerning administration, law, architecture, and many other aspects of daily life.

A Note on Islam

It is perhaps worth noting at the start that the spread of Islam in Africa was much more than the passing on and adoption of religious ideas. As the UNESCO General History of Africa summarises, unlike many other faiths:

Islam is not only a religion: it is a comprehensive way of life, catering for all the fields of human existence. Islam provides guidance for all aspects of life – individual and social, material and moral, economic and political, legal and cultural, national and international. (Vol III, 20)

It is thus perhaps more comprehensible, given the above, why so many African rulers and elites were ready to adopt a foreign religion when it also brought with it definite advantages of governance and wealth.

Geographical Spread

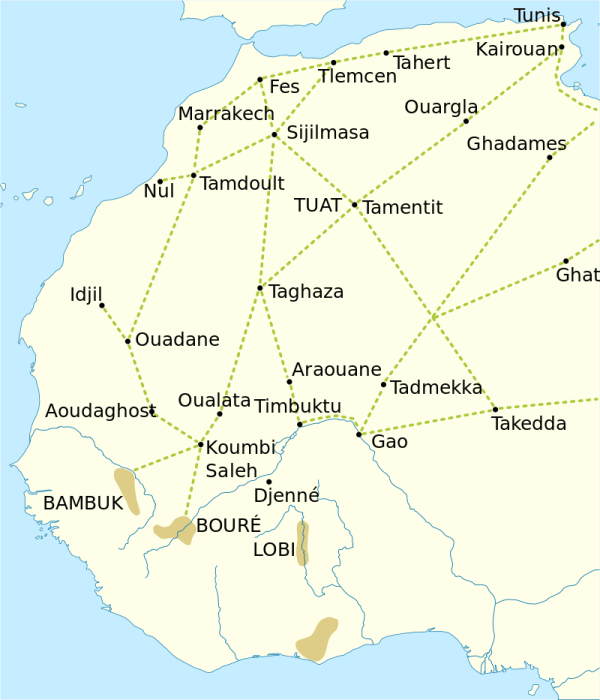

Islam spread from the Middle East to take hold across North Africa during the second half of the 7th century CE when the Umayyad Caliphate (661-750 CE) of Damascus conquered that area by military force. From there, it spread via Islamized Berbers (who had been variously coerced or enticed to convert) in the 8th century CE along the trade routes which crisscrossed West Africa, moving from the east coast into the interior of central Africa, finally reaching Lake Chad. Meanwhile, the religion also spread down through Egypt and swung westwards through the Sudan region below the Sahara Desert. A third wave brought the religion to Africa’s eastern shores, the Horn of Africa and the Swahili Coast, directly from Arabia and the Persian Gulf.

Once the religion had reached the savannah region which spreads across Africa below the Sahara Desert, it was adopted by ruling African elites, although very often indigenous beliefs and rituals continued to be practised or were even blended with the new religion. As Muslim traders penetrated deeper into Africa so the religion spread from one empire to another, taking hold first at Gao in 985 CE and then within the Ghana Empire (6th-13th century CE) from the late 10th century CE. From there, the religion spread eastwards to the Mali Empire (1240-1645 CE) and the Songhai Empire (c. 1460 – c. 1591 CE). With the adoption of Islam by the rulers of the Kingdom of Kanem (c. 900 – c. 1390 CE) between the 11th and 13th century CE and Hausaland from the late 14th century CE, the religion’s encirclement of Africa below the Sahara Desert was complete.

In East Africa, Islam faced stiff competition from Christianity which was firmly entrenched in Nubia and states such as the Kingdoms of Faras (aka Nobatia), Dongola, and Alodia, and in the Kingdom of Axum (1st – 8th century CE) in what is today Ethiopia. It was not until the 14th century CE and military intervention from the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt (1250-1517 CE) that these Christian kingdoms became Muslim, the exception being the Kingdom of Abyssinia (13th-20th century CE). In addition, two important Muslim states in the Horn of Africa were the Sultanates of Adal (1415-1577 CE) and Ajuran (13-17th century CE).

Islam had more immediate success further south on the Swahili Coast. From the mid-8th century CE, Muslim traders from Arabia and Egypt began to permanently settle in towns and trading centres along the Swahili coast. The local Bantu peoples and Arabs mixed, as did their languages, with intermarrying being common, and there was a blending of cultural practices which led to the evolution of a unique Swahili culture. Islam was more firmly established from the 12th century CE when Shirazi merchants arrived from the Persian Gulf. As the historian P. Curtin puts it: “The Muslim religion ultimately became one of the central elements of Swahili identity. To be a Swahili, in later centuries, meant to be a Muslim” (125). Islam was a success on the coast but it made no impact at all on peoples living in the interior of East Africa until the 19th century CE.

There were other challenges besides the Christians of Nubia. There were many who vehemently held on to their traditional beliefs in the face of this new religion. Another group which fought against the tide of Islam were the Mossi people, who controlled the lands south of the Niger River and who attacked such cities as Timbuktu in the first half of the 15th century CE. Then the Christian Portuguese arrived in Africa on both the West and East coasts where they challenged the spread of Islam. Where the Europeans traded extensively such as on the western coast of Africa states like the Kingdom of Kongo (14-19th century CE) became Christian, and from the 16th century CE, Islamic domination of the Swahili coast was challenged.

Reasons For Adoption

Aside from genuine spiritual conviction, African leaders may have recognised that adopting Islam (or seeming to) or at the least tolerating it would be beneficial to trade. The two spheres of Islam and trade are closely intertwined, as here explained in the UNESCO General History of Africa:

The association of Islam and trade in sub-Saharan Africa is a well-known fact. The commercially most active peoples, the Dyula, Hausa and Dyakhanke, were among the first to be converted when their respective countries came into contact with Muslims. The explanation of this phenomenon is to be found in social and economic factors. Islam is a religion born in the commercial society of Mecca and preached by a Prophet who himself had for a long time been a merchant, provides a set of ethical and practical prescripts closely related to business activities. This moral code helped to sanction and control commercial relationships and offered a unifying ideology among the members of different ethnic groups, thus providing for security and credit, two of the chief requirements of long-distance trade. (Vol. III, 39)

However, in the Ghana Empire, for example, there is no evidence that kings themselves converted to Islam, rather, they tolerated Muslim merchants and those from Ghana who wished to convert. Ghana’s capital at Koumbi Saleh was, significantly, divided into two distinct towns from the mid-11th century CE. One town was Muslim and boasted 12 mosques while the other, just 10 km away and joined by many intermediate buildings, was the royal residence with many traditional cult shrines and one mosque for visiting merchants. This division reflected the continuance of indigenous animist beliefs alongside Islam, the former being practised by rural communities.

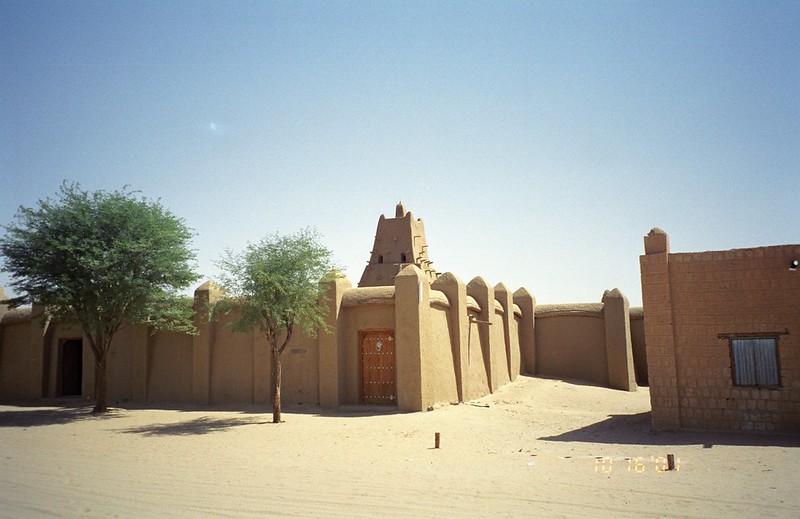

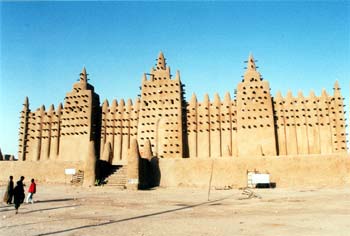

In contrast, in the Mali Empire, the kings did convert to Islam, the first certain case being Mansa Uli (aka Mansa Wali or Yerelenku), who went on a pilgrimage to Mecca in the 1260s or 1270s CE. Many subsequent rulers followed suit, most famously Mansa Musa I (r. 1312-1337 CE) who visited Cairo and Mecca and brought back to Mali Muslim scholars, architects, and books. Mosques were built such as Timbuktu’s Great Mosque (aka Djinguereber or Jingereber), and Koranic schools and universities were established which quickly gained an international reputation. One noted Timbuktu scholar was the saint Sharif Sidi Yahya al-Tadilsi (d. c. 1464 CE) who became the patron saint of the city. A clerical class developed, many of whose members were of Sudanese origin, and many frequently acted as missionaries, spreading Islam into the southern parts of West Africa.

As more people were converted, so more Muslim clerics were attracted from abroad and the religion was spread further across West Africa. Many native converts studied in such places as Fez, Morocco, and became great scholars, missionaries, and even saints, and so Islam came to be seen no longer as a foreign religion but a black African one. Finally, Muslim clerics often made themselves very useful to the community in practical daily life (and so they increased the appeal of Islam) by offering prayers on request, performing administrative tasks, offering medical advice, divining – such as the interpretation of dreams, and making charms and amulets.

Another motivation for rulers to adopt Islam besides greater riches with which to impress their people and hold on to power was that a new dynasty may have been bolstered in its claims of legitimacy by also adopting a new religion. This could well be the most important factor in the Kingdom of Kanem’s adoption in the late 11th century CE. Adopting Islam permitted, too, the exchange of diplomatic embassies with North African states, as well as the possibility to send scholars for training, both of which brought the sub-Saharan states, in particular, into contact with the wider Mediterranean world and increased the prestige of rulers. Yet another appeal of Islam was that it brought literacy, a tremendously useful tool for empires who built their wealth on trade.

Rulers were not always so keen to adopt Islam, King Sunni Ali of the Songhai Empire (r. 1464-1492 CE), for example, was vehemently anti-Muslim, but King Mohammad I (r. 1494-1528 CE) did convert, and he imposed Islamic law on his people and appointed qadis (Islamic magistrates or judges) as heads of justice at Timbuktu, Djenne, and other towns. As in Ghana and Mali, though, the rural populace of Songhai remained stubbornly loyal to their traditional beliefs.

Accommodating Ancient African Beliefs

As noted, ancient indigenous beliefs continued to be practised, especially in rural communities, as recorded by travellers like Ibn Battuta who visited Mali c. 1352 CE. In addition, Islamic studies were, at least initially, conducted in Arabic, not native languages, and this further impeded its popularity outside the educated clerical class of towns and cities. Even the Islam that did take hold was a particular variation of that practised in the Arab world, perhaps because African rulers could not afford to completely dismiss the indigenous religious practices and beliefs that the majority of their people still clung onto and which very often elevated rulers to divine or semi-divine status.

Even on the Swahili Coast, which adopted Islam with perhaps more success than anywhere else, many converts continued the practice of appeasing spirits who brought illness and other misfortunes. Ancestors continued to be worshipped, in some cities women enjoyed better rights than they did under strictly sharia law, and, in a very un-Islamic practice, cemeteries were filled with tombs where precious goods were buried with the dead.

Cultural Impact

Islam had profound effects on all aspects of daily life and society but these did vary over time and place. The coming of Islam saw a general decline in the status of certain groups in ancient African communities. One of the chief losers were the metalworkers who had always enjoyed a mystical reverence from ordinary people because of their skills in forging metal. The same applies to those who found and mined such precious metals as gold and iron. In contrast, an association with Islam sometimes brought a certain prestige, a point seen most clearly in the re-recording of community histories and foundation myths to include the arrival of a founder from the East. It is also true that in some cases oral traditions maintained their cultural integrity, and thus we are presented with a parallel history such as seen in the biographies of Sundiata Keita (r. 1230-1255 CE), the founder of the Mali Empire, who in written history converted to Islam but in oral tradition was a great magician of the indigenous religion.

Men and women’s roles sometimes changed, some African communities having previously given women a more equal status with men than was the case under Muslim laws. Some African societies were matrilineal, and these changed to a patrilineal system. More superficial changes included the changing of names to those favoured by Muslims. Often such names were adapted to suit African languages, for example, Muhammad became Mamadu and Ali was Africanized to Aliyu. Clothing changed, too, with women, in particular, encouraged to dress more modestly and adolescents to cover their nudity.

Islamic architecture spread with the religion with mosques being built wherever there were worshippers. However, just like the religion itself, there were minor local differences. Mosques on the Swahili Coast, for example, had neither the minarets or inner courtyard typical of mosques elsewhere in the Islamic world.

There were several technical innovations that came with Islam such as writing, numbers, mathematics, measurements and weights. Not only did Muslim scholars and missionaries visit and stay in African communities but also Muslim travellers and chroniclers like Ibn Battuta and Ibn Khaldin (1332-1406 CE) who made invaluable observations and records of African life in the medieval period. These writers, along with archaeology, have helped enormously in the reconstruction of ancient Africa following the European colonial period where every attempt was made to obliterate the history of the continent lest it conflict with the racist belief that Africa had long been waiting to be civilised.

Bibliography

- Curtin, P. African History.Pearson, 1995.

- Fage, J.D. (ed). The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 2.Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Hrbek, I. (ed). UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. III, Abridged Edition.University of California Press, 1992.

- Insoll, T. “The Archaeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Journal of World Prehistory, Vol. 10, No. 4 (December 1996), pp. 439-504.

- Ki-Zerbo, J. (ed). UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. IV, Abridged Edition.University of California Press, 1998.

- McEvedy, C. The Penguin Atlas of African History.Penguin Books, 1996.

- Ogot, B.A. (ed). UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. V, Abridged Edition.University of California Press, 1999.

- Oliver, R. (ed). The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 3.Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Oliver, R.A. Cambridge Encyclopedia of Africa.Cambridge University Press, 1981.

- de Villiers, M. Walker Books, 2007.