Notes of history

Muslims in Madrid’s street directory

Madrid had a historical Islamic presence lasting more than 700 years. The city was founded in the second half of the 9th century by Emir Muḥammad I and was part of al-Andalus until its conquest by Alfonso VI in the 11th century, remaining under Islamic rule for more than two centuries. The Islamic presence continued after the Andalusi period with a Mudejar and Morisco community, including the influx of Moriscos from Granada who were deported or enslaved. In addition, other forms of Muslim or crypto-Muslim presence extended beyond the expulsion of the Moriscos, such as slaves of Muslim origin, exiles, hostages, renegades and ambassadors.

Despite this extensive history, there are few traces and reminders of this centuries-old Islamic presence in Madrid’s place names, both in traditional and commemorative names. The hegemonic view in Spain, with medieval roots and consolidated in the 19th century, has considered Islamic identity to be foreign and hostile, seeing the ‘Reconquista’ as the great founding myth of the nation. In Madrid, historiographical accounts often dispute the Andalusi foundation, promoting the idea of a pre-Islamic origin to align the city with the myth of the ‘Reconquista’.

This article analyses how this historical footprint is reflected in urban place names. To this end, it analyses the names recorded since 1835 and examines the historical or legendary narratives that link certain places in the street map with the Islamic presence (usually embodied in the stereotypical figure of the Moor), based on an examination of various reference works on Madrid place names.

Traces of the past in urban place names

Traces of the Andalusis and Mudejars

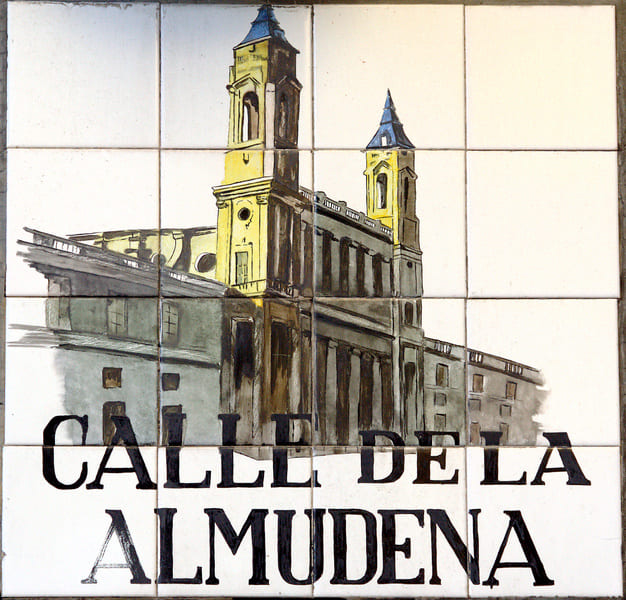

Few place names in Madrid are a direct survival of the historical Islamic presence. A notable example is the name of Madrid’s patron saint, La Almudena, which name comes from the Arabic al-mudayna, referring to the Islamic walled enclosure or part of it. Although the Almudena arch (demolished in 1570) and the church of Santa María de la Almudena (a former mosque, demolished in 1869) no longer exist, the name lives on in the 19th-century cathedral and the small street of Almudena. The illustrated plaque on Calle de la Almudena depicts the façade of the cathedral, without referencing the Andalusi origin of the name.

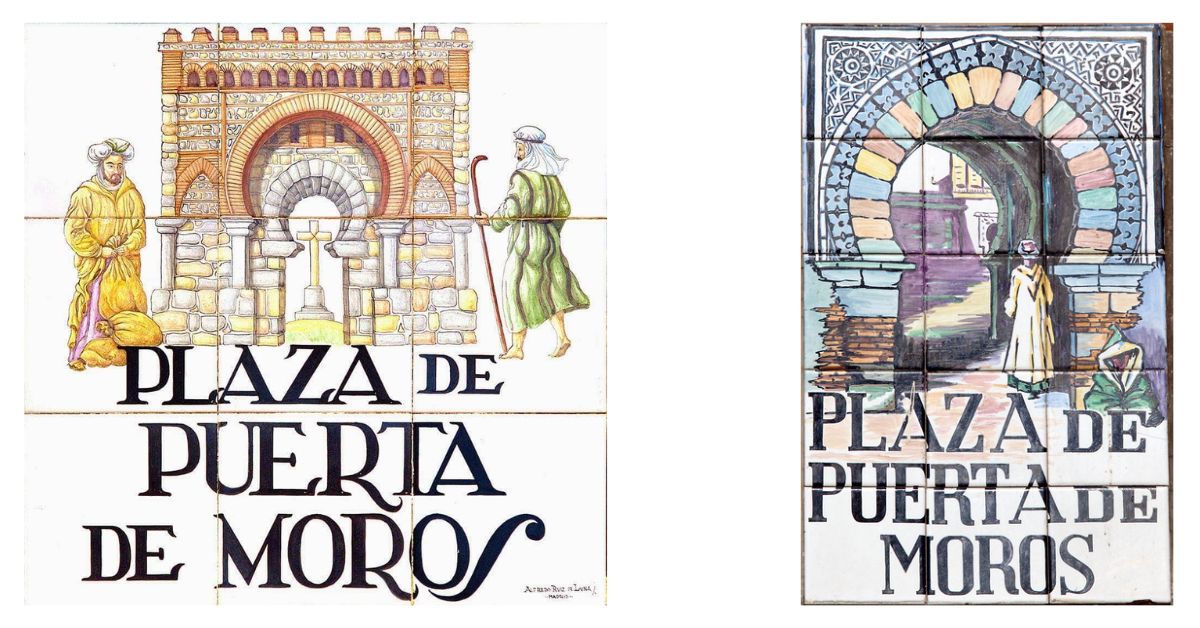

From the Mudejar period, the place names La Morería (Moorish Quarter) and Puerta de Moros (Moorish door) remain, located in the old Moorish Quarter, an area of Muslim settlement. Although there was a new Moorish Quarter, it left no clear trace in the place names, except perhaps for streets named after metal craftsmen such as Cuchilleros (knifemakers) and Latoneros (brass worker) (formerly called “Herrería”), which may have had a connection with Mudejar craftsmen.

The Old Moorish Quarter features several graphic representations. The Plaza de la Puerta de Moros has two tile cartouches: one by Ruiz de Luna and the other by the Madrid School of Ceramics from the 1960s. Ruiz de Luna’s plaque shows a horseshoe archway framing a cross (perhaps to highlight the Mudejar context) and two men with stereotypical ‘Moorish’ features (tunic, turban, beard). The other plaque presents a less imaginary iconography, inspired by Moroccan colonial prints, such as those produced by Mariano Bertuchi, a painter from the Spanish protectorate in Morocco, which must have been still alive in the collective imagination at the time the plaques were made.

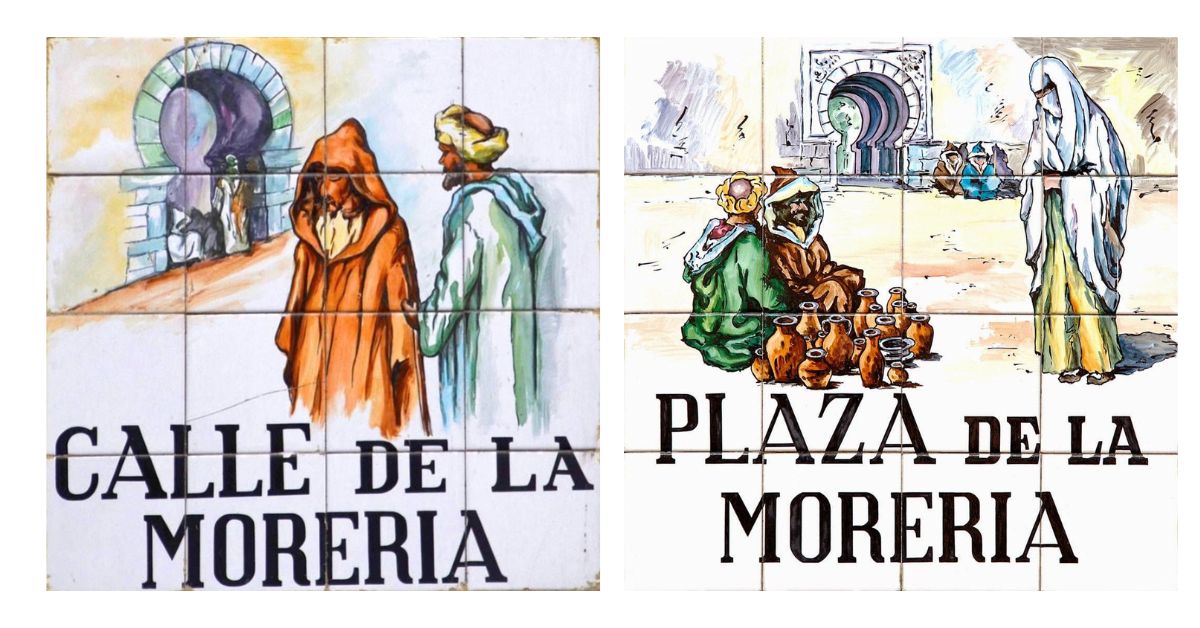

The plaques in the square and street of La Morería also date from the 1960s and feature the same colonial inspiration, depicting figures wearing bathrobes, djellabas and turbans, with a sombre and hieratic air that reflects colonial stereotypes of indolence and decadence.

Traces of the Modern Age: Moriscos and slaves

There is no apparent trace of the Moriscos of Madrid in the place names, except that they helped to preserve the name of La Morería Vieja, where the native Morisco population was concentrated in the 16th century. Moriscos from Granada, enslaved or deported after the War of the Alpujarras, concentrated in the suburbs of San Ginés and San Martín. Although this is conjecture, the abundance of place names related to textile trades in the area (Farriers, Rowers, Bonetillo, Embroiderers, Colourists) could be related to them. In addition, the slave-owning society left behind some streets named after black people, of which only one remains today.

Foreign footprints

Few notable foreign Muslims who resided in Madrid as ambassadors, exiles or hostages left their mark on the city’s place names. The oldest is Calle Embajadores (Ambassadors’ Street). According to tradition, its name dates back to the reign of Juan II (1406-1454), when ambassadors from France, Aragon, Navarre and Tunisia settled there fleeing the plague. Ruiz de Luna’s graphic representations show the three Christian ambassadors, but not the Muslim one.

Another, more controversial trace is that of Calle del Príncipe (Prince Street). One hypothesis links it to Muley Xeque (Mawlāy al-Šayj), the ‘Prince of Morocco’ or ‘Black Prince’, son of the Alawite sultan, who went into exile in Spain and was baptised in 1593. The street could commemorate the location of his house. However, Mesonero Romanos and Répide attribute the name to Philip II during his time as prince. Although the name already existed before the arrival of Muley Xeque, a baptismal certificate from 1602 refers to the ‘Calle del Príncipe de Marruecos’, suggesting a later association. The plaque by Ruiz de Luna depicts the face of Philip II as prince.

Finally, Calle del Turco (now Marqués de Cubas) was so named because it housed Turkish embassies in the 16th and 17th centuries. Teresa de Jesús also refers to an earlier Turkish presence. Tradition did not preserve the names of these Ottoman emissaries.

Legendary traces

Locations legendarily associated with the Islamic presence are much more abundant, sometimes depicted in graphic representations. One of the most obvious is the Campo del Moro park. Mesonero Romanos links it to the camp of the ‘king of the Almoravids Tejufin’ (Almoravid emir ‘Alī b. Yūsuf b. Tāšufīn) who attacked Madrid in 1109, an expedition that is historically disputed. The name is probably a historicist attribution from the early 19th century, influenced by José Antonio Conde’s translation of Ibn Abī Zar’s Rawḍ al-qirṭās.

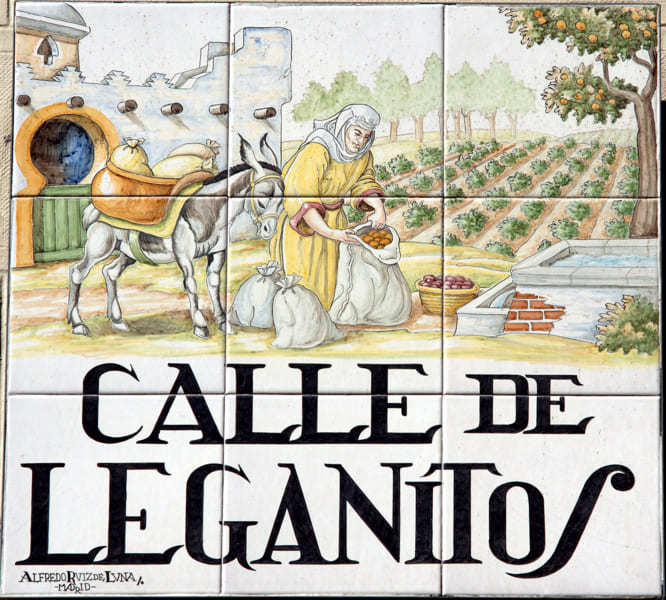

Leganitos Street, documented since 1574, is said to derive from the Arabic algannet (“the orchards”), given that the area was covered in orchards during the Moorish period in Madrid. Ruiz de Luna’s illustration shows a peasant woman of ‘Moorish’ appearance next to vegetable gardens and a building with stereotypical Arab-Islamic features (stepped battlements, horseshoe arch).

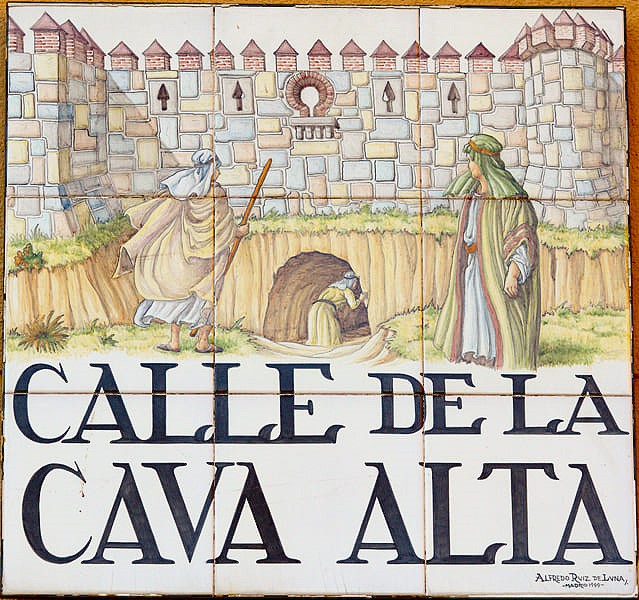

Other streets are traditionally associated with sites or infrastructure from Andalusi and/or Mudejar Madrid, such as Cava Alta and Cava Baja. The various authors consulted agree that the word ‘cava’ does not refer to mines or tunnels that allowed entry or exit from the town, used to escape during Christian attacks. The plaque on Cava Alta shows stereotypical Arab characters entering the walled city through a tunnel. It is unlikely that these mines date back to ‘Arab’ times, as they are located in the Christian wall built after the conquest by Alfonso VI.

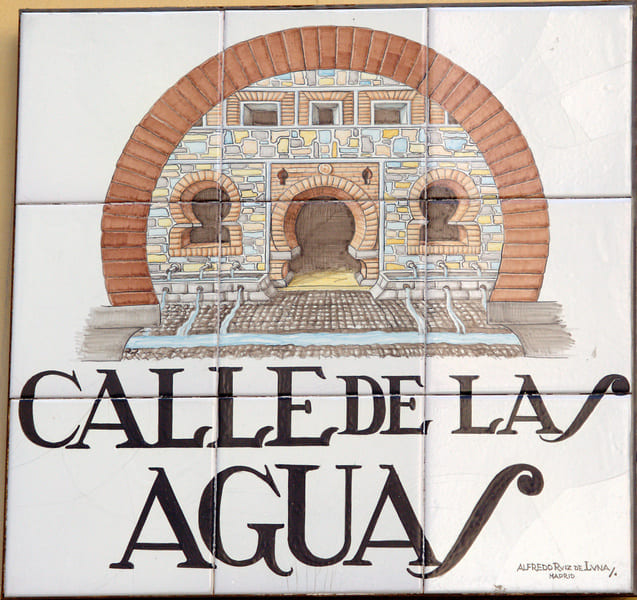

Some traditions place the bathhouse or ḥammām, supposedly demolished by Alfonso the Wise, on Calle de las Aguas (street of the waters). The street sign shows a building with fountains and marked horseshoe arches, suggesting a stereotypical Andalusian origin. The baths have also been located in Elissabeth II Square (Plaza de Isabel II) and the old Calle de los Caños. Capmany suggests that two spouts supplied water to the baths outside the Barnadu gate. Although the existence of medieval baths of Andalusian origin is documented, their exact location is disputed.

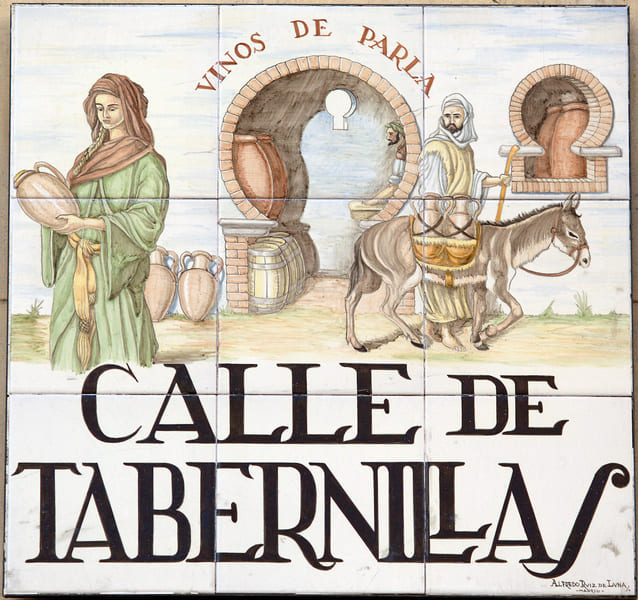

Even less substantiated legends include Calle de Alfonso VI (within the Old Moorish Quarter), which is said to be where Alfonso VI entered after the reconquest of Madrid. Formerly called Calle del Aguardiente, Capmany echoes a legend according to which medieval brawls between ‘Moors’ and Christians were frequent in this street, due to the effects of the aguardiente (spirits) sold there and consumed by both communities. The insistence on linking Muslims with alcohol consumption (a practice prohibited in Islam) is repeated in the case

of the nearby Calle Tabernillas. The plaque by Alfredo Ruiz de Luna does represent this Islamic affiliation of the tabernillas. It shows a wine shop with a door and window in the shape of a horseshoe arch and the legend ‘wines from Parla’. In front of it walks a Moorish-looking man (turban, tunic, beard) with a donkey loaded with amphorae. The man’s gaze is directed towards a woman with a visible blonde braid (to show that she is not Moorish?), while inside the premises another individual with the same appearance as the previous one can be glimpsed.

In other legends, Islam appears as an antagonist or an unwanted presence. Calle del Espíritu Santo (Holy Spirit Street) is linked to a fire caused by lightning that destroyed some Moorish shops, interpreted as divine will to justify their elimination. In memory of this event, a stone cross with a dove in the middle was erected, called the Cruz del Espíritu Santo, from which the street takes its name.

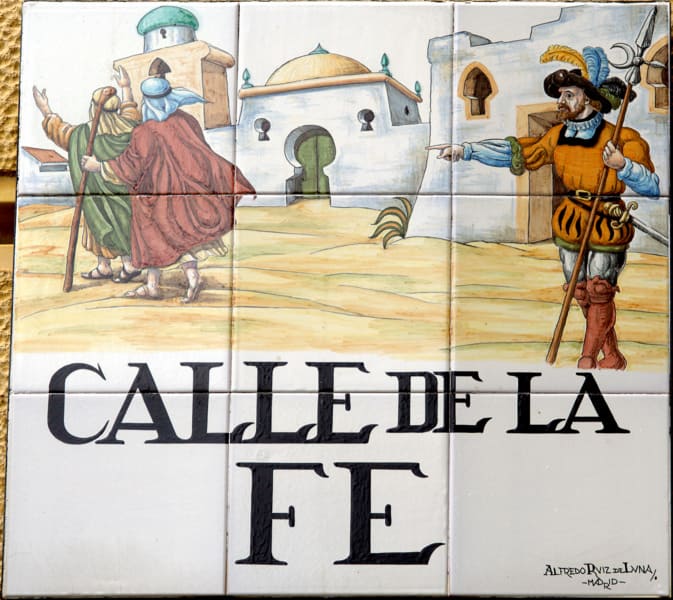

The Lavapiés neighbourhood is popularly associated with Islamic and Jewish presence. Although there is no archaeological evidence, tradition places a Jewish quarter with a synagogue on Calle de la Fe (Faith Street). The current plaque by Ruiz de Luna shows a soldier expelling figures who, based on their attire and surroundings, appear to be more Muslim than Jewish. It shows a soldier dressed in 16th-century style expelling figures who, based on their attire and surroundings (houses with domes, horseshoe arches, etc.), appear to be more Muslim than Jewish.

Several Marian invocations reflected in the street names are framed within the dialectic of the ‘Reconquista’ and the fight against the ‘Moors’. The legend of La Almudena associates Muslims with the desecration of Christian images, narrating how the image of the Virgin was hidden in a niche in the wall in 712 to protect it from the Moorish advance and miraculously found after the ‘Reconquista’. This is an ahistorical tradition which, as in other conquered places, seeks to create a timelessness that legitimises the rhetoric of the ‘recovery’ of the city.

The street and roundabout of Atocha owe their name to the Virgin of Atocha. The legend comes from Jerónimo de Quintana (author of several of the ‘traditions’ that, during the Habsburg period, sought to attribute an ancient and illustrious origin to Madrid) and is recounted by Peñasco and Cambronero:

“The tradition of Our Lady of Atocha is as follows, according to Quintana: Gracián Ramírez, a valiant leader of the 8th century, having learned that, during the Saracen invasion, a certain image of the Virgin had been hidden in an atochar (a place planted with atochas or esparto grass), came in search of it and built a chapel for it. When the Moors heard of this, they attacked him in great numbers, and the brave Gracián, taken by surprise, went out to meet them, but not before slaying his wife and daughters to spare them from the ferocity of the enemies, before whom he expected nothing but defeat and death, or captivity. Fortune favoured him, and after defeating the followers of Mohammed, he returned to the hermitage, where he found his wife and daughters safe and sound, praying at the feet of the sacred image”.

Peñasco y Cambronero. Las calles de Madrid, p. 84.

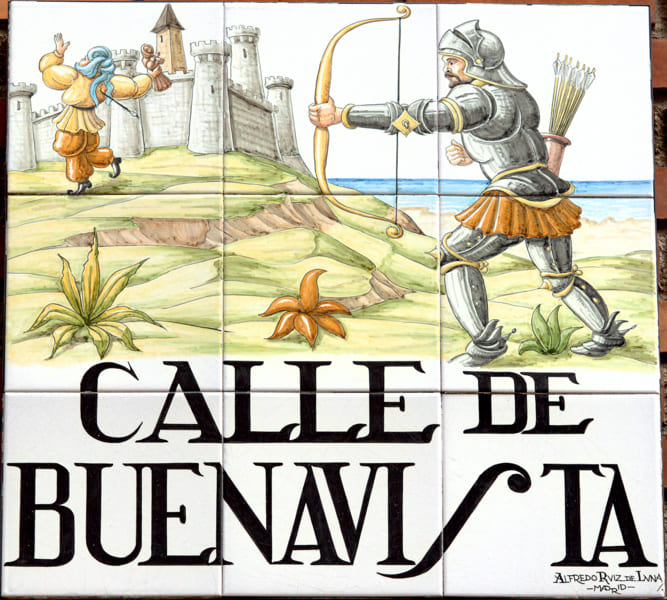

As for Buenavista Street, tradition places here the house of Basilio Sebastián Castellanos, who during the Battle of Algeciras (1278) killed a Muslim to seize an image of the Virgin Mary from him. Ruiz de Luna’s plaque shows the knight killing the ‘Moor’ from behind as he flees with the Marian image.

Madrid has street names dedicated to the triumph over Islam and Muslims, where the ‘enemy’ is often barely mentioned or invisible. The plaque in Plaza de Santiago (Santiago Square) depicts the supernatural appearance of the apostle in the Battle of Clavijo (844) riding a white horse, hence his nickname ‘Matamoros’ (Killer of Moors), although this representation does not conform to the usual iconography in which Muslims are crushed by the horse.

Making the other part of us

The idea of dedicating a place to Muḥammad I, the founder of Madrid, was proposed in 1945 and came to fruition in late 1986, when the City Council named the park next to the remains of the Andalusian wall after him. The proposal was supported by all political groups, with the request to add the title of ‘emir’ to distinguish him from other dynasties and ‘to show that he belongs to the Spanish dynasties’.

Another commemorative name related to Andalusian Madrid is Plaza de Maslama al-Maŷriti, (Maslama al-Maŷriti Square) which commemorates an Arabic-speaking mathematician, astronomer and alchemist born in Madrid in the 10th and 11th centuries. The name of this small square was assigned in 1985. In 2019, the demonym ‘al-Maŷriti’ (“the Madrilenian”) was added.

A third name commemorates another notable Andalusian, in this case not related to Madrid: Averroes (Ibn Rušd). His small street in the Niño Jesús neighbourhood was approved in 1932 by the City Council of the Republic, as part of a series of streets named after universal figures in art and culture, suggesting that the intention was not necessarily to commemorate Spain’s Islamic past.

Conclusion

Of the more than sixteen thousand names that have made up Madrid’s street map since 1835, only two explicitly commemorate the city’s Andalusi origins: Emir Mohamed I Park and Maslama Square (later Maslama al-Maŷriti). Both were created in the 1980s, with Emir Mohamed I being the only one with a conscious intention to activate the heritage of the Andalusian past. If we add the small Averroes Street, this completes all the explicit references to figures from the history of al-Andalus in Madrid’s street names. There are no names commemorating the Mudejar or Muslim presence in the Modern Age.

There are traditional or customary names that are linked, historically or legendarily, to the Islamic presence (Andalusian, Mudejar, modern), although this link is not always evident nor does it have a clear evocative value. These evocations are often part of a stereotypical representation of Muslims as antagonists or exotic counterpoints to the “authentic us”, a presence that was eventually expelled. The clearest cases are Morería and Puerta de Moros, which, in addition to their explicit names, have graphic representations that reinforce exoticising stereotypes.

Other streets do not refer to the Islamic presence in their names, but they do so through their illustrated plaques, such as Leganitos, Tabernillas, Aguas, Buenavista, and Fe. These references can be neutral or, as in the last two examples, clearly negative, representing Muslims as antagonists. On the contrary, there are numerous names commemorating the centuries-long struggle against Islam, such as those dedicated to episodes and figures from the Reconquista (Alfonso VI, Battle of Salado, Jaime the Conqueror, Navas de Tolosa, Witiza) or the Battle of Lepanto.

Despite the prolonged Islamic presence in the history of Madrid, its mark on urban place names is scarce and, when it does exist, it is often mediated by stereotypes or legendary accounts. The few explicit commemorative names are recent and few in number. In contrast, a nationalist narrative has been reinforced that glorifies the “Reconquista” and presents Islam as an enemy. This symbolic inequality is not accidental, but the result of a persistent ideological construction. Questioning it is a necessary step towards a more just and pluralistic urban memory.

The information in this article has been taken from: Gil‑Benumeya Flores, D. (2022). La huella y la representación del Otro: los musulmanes en el callejero madrileño. Miscelánea de Estudios Árabes y Hebraicos. Sección Árabe-Islam, 71, 109–149.

Access the full article here (original article in Spanish).

Este artículo está disponible en Español.

Images © Pedroreina