Articles, Contemporary Mayrit, Mayrit hoy

Madrid, the Andalusian city with many streams

Article author: Dr. Mohammed Chtatou *

Date of publication of the article: 05/08/2023

Year of publication: 2023

Article theme: Al-Andalus, Archaeology, Architecture, History, Madrid, Mayrit.

The history of Madrid began in the ninth century, when the Umayyads decided to build a line of fortifications in the center of the Iberian Peninsula to defend the borders of Al-Andalus.

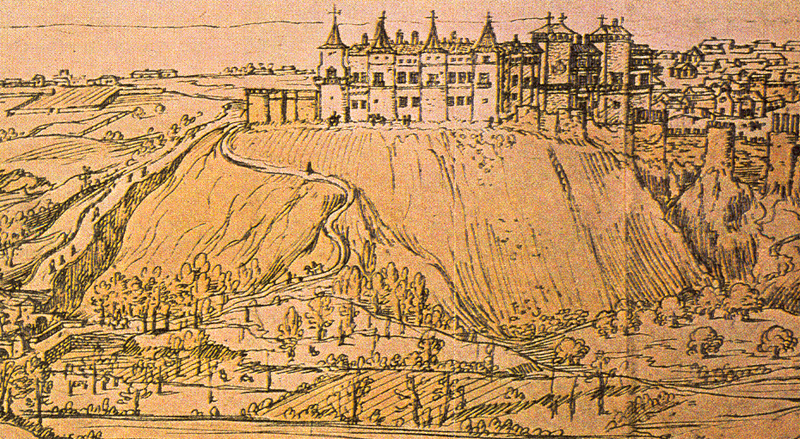

Around the year 865, Muhammad I, son of Abderraman II, ordered the construction of fortifications around the village of Magerit, formerly known as Matrice, a name that referred to the water in the area and the stream that ran through the street of Segovia.

Madrid was founded as a hisn حصن (fort), but soon historical sources began to refer to it as a madina sagira (a small city) or al-mudeyna. It became a center of attraction for the civilian population, as well as the capital of a small region. On its account, the Moroccan geographer al-Idrissi wrote in the twelfth century: [i]

“Among the cities with minbars at the foot of these mountains is Madjrit, a small town and a powerful and prosperous fortress. It had, in the Islamic era, a large mosque where sermons were regularly given. “

The only Christian source that made a mention of Madrid before the Castilian conquest in the 11th century is a chronicle by Bishop Sampiro de León [ii] in which he tells how King Ramiro II of Asturias, in one of his expeditions against the land of the “Chaldeans” (a way of referring to the Muslims), attacked and destroyed the walls of “the city they call Magerit. ” Magerit was the medieval Latin and Castilian way of transcribing the Arabic “Majrit” مجريط, origin of the current name of the city.

But two centuries later, in 1083, the king of Castile, Alfonso VI, known as “The Brave”, reconquered the town where Moors, Jews and Christians continued to live together for many years. From the fusion of the Arabic and Roman names, the toponym Madrid was born. [iii]

History of Madrid: origins of the Spanish capital

Majrit, “land full of water”, was the name given by the Arabs to the plain near the Sierra de Guadarrama chosen by Philip II to establish his court and which would later become the city as we know it today.

The first historical evidence of Madrid dates back to 865 when Emir Mohammed I ordered the construction of a kasbah in the town of Majrit, on the banks of the Manzanares River. Majrit means in Arabic “abundance of water”, which is why the first coat of arms of the city bore the motto:

“I was built on water /

My walls are of fire /

These are my insignia and my coat of arms. “

Until 1083, when Alfonso VI of Castile conquered the city, Madrid professed the Muslim faith.

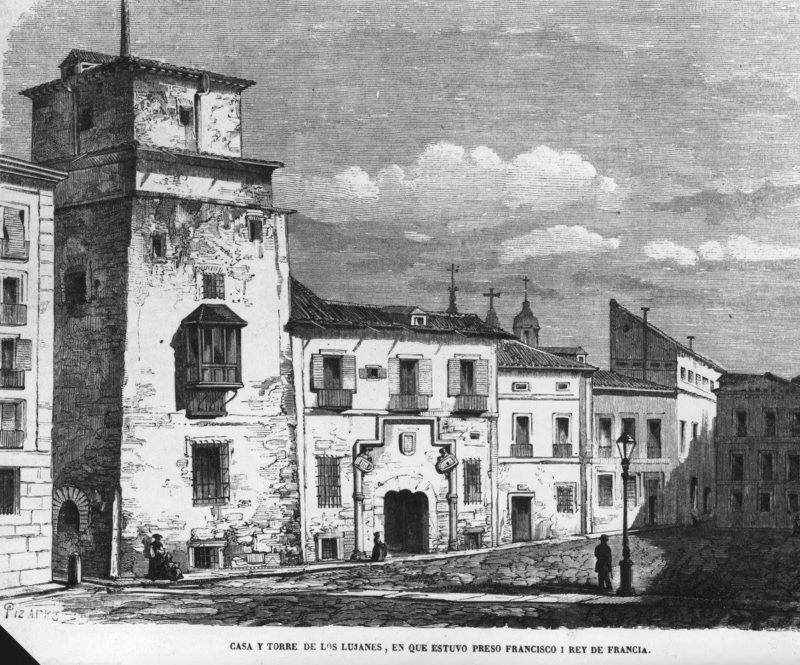

There are few vestiges of the Madrid of that period. In Calle Mayor, next to the Italian Institute of Culture, in the same place where the Church of Santa María would be built later (some of its ruins are still visible), stood the Great Mosque, probably surrounded by the souk as was common in Islamic cities. A few steps away, in the Cuesta de la Vega, one can still see the remains of the old walls. This place was called almudaina المدينة or ciudadela.

When the city was taken, the Christians discovered a sculpture of the Virgin hidden in the walls, lit by a candle that had been burning for over four hundred years. From then on, the Almudena (al-mudeyna) would be the invocation of the Virgin Mary for the people of Madrid.

Madrid is therefore the only European capital with a Muslim origin and background. In fact, it is even older than many of the important Arab cities of today. For the first two and a half centuries of its existence, it was located in the far north of the classical Muslim world, which at that time extended from the Duero River to the Sahara Desert and from the Atlantic Ocean to the borders of China.

Recovered history

Indeed, the name of Madrid originates from the Arabic word majrâ مجرى > majrit مجريط, which means small stream in classical Arabic. Founded in the middle of the 9th century by the Umayyad emir Muhammad I as a military base, the city remained under Muslim rule for two centuries. [iv]

On the origin of the name of Madrid, Christine Mazzoli-Guintard points out: [v]

“As for the name of the small town, Mağrīṭ, the debate on the Latin or Arabic origin of the toponym remains open; Latin for the scholars of the thirteenth century and until the middle of the sixteenth century, Arabic for the scholars of the second sixteenth century and until the eighteenth century, Latin again for the scholars of the nineteenth century, it still divides Spanish Arabists: to the proponents of the Arabic theory, developed by J. Oliver Asín and supported by Ma J. Rubiera Mata, is opposed by the Latin theory, developed by J. Coromines and followed by F. Corriente and M. Marín. The debate, however, has forgotten the fundamental element of the settlement of early Madrid, the presence of the Berbers: settled in the area at the time of the foundation, their memory seems to have been totally obscured by the emirate’s decision to fix by an Arabic term, mağrā, the running water, the settlement of the men. “

Nevertheless, this stage of Madrid’s life is not well known by tourists and even by many locals who do not know that their city was, at one time in history, one of the fortresses of al-Andalus. To remedy this situation, the Madrid City Council has recently published a guide to inform about those two centuries when the capital was part of al-Andalus and to highlight its Arab origins.

“Madrid islámico: La historia recuperada” (Muslim Madrid: Recovered History) is the title of this book writen by Daniel Gil-Benumeya and published by the Center for Studies on Islamic Madrid (CEMI), created by the Islamic Culture Foundation (FUNCI). [vii]

“Madrid islámico: La historia recuperada” (Muslim Madrid: Recovered History) is the title of this book writen by Daniel Gil-Benumeya and published by the Center for Studies on Islamic Madrid (CEMI), created by the Islamic Culture Foundation (FUNCI). [vii]

Among the ruins reminiscent of this period are part of the Arab wall in the park of the emir Muhammad I, as well as a portion of another Arab wall now located under a building in a street in the center of the capital, an Arab watchtower from the 10th century now located in an underground public parking lot in Plaza Oriente or a silo from the Arab-Muslim period in Plaza de Ramales.

The guide published by the CEMI also includes stories related to the Arab-Muslim past of the city and refers to several Spanish words and expressions of Arabic origin used until today.

Several of Madrid’s disappeared Arab monuments are also mentioned in the guide, as well as the objects used in that era, a large number of which are on display at the San Isidro Museum, which now has an entire room dedicated to Arab archaeology.

In Calle Mayor, next to the Italian Institute of Culture, in the same place where the Church of Santa María would be built later (some of its ruins are still visible), stood the Great Mosque, probably surrounded by the souk as was common in Islamic cities.

Several objects and archaeological remains from the al-Andalus era, discovered during excavations for urban projects in the heart of Madrid or during archaeological digs, are on display in this museum. These remains allow visitors to imagine what social, economic and political life was like in Mayrit.

The guide published by the CEMI also includes stories related to the Arab-Muslim past of the city and refers to several Spanish words and expressions of Arabic origin used until today. The initiative to publish this book confirms the existence in today’s Spanish capital of vestiges of the Arab-Muslim golden age in Spain, which are mentioned in some history books.

On this particular point Kira Walker writes in an article entitled: “The hidden Islamic history of Madrid revealed,“ in The Middle East Eye: [viii]

“Efforts to recover and safeguard the city’s Islamic heritage have intensified in recent years, largely under the direction of Spain’s Islamic Culture Foundation (FUNCI). Encarna Gutierrez, the foundation’s secretary general, says it was developed in the belief that Spain needed to embrace its multi-cultural heritage, and that education needed to play a part in this cultural acknowledgement. In 2017, the foundation partnered with the Complutense University of Madrid to establish the Centre for the Study of Islamic Madrid (CEMI). “

She goes on to say forcefully:

“That the Islamic history of Madrid remains so little known to this day is down to two key reasons.

The first, says Gil-Benumeya, is that the city is the capital of Spain, encapsulating the idea of the imagined Spanish community – which is Catholic and European – and all its myths. He explains that in 1561, King Felipe II made Madrid the permanent seat of his court: soon after the city’s material and symbolic medieval past were erased to build a capital worthy of the growing empire. Part of this process involved inventing several heroic myths relating to Madrid’s history – but in doing so the city’s Islamic origins were radically suppressed. “This narrative cannot be defended from a scientific point of view, but is deeply rooted in the popular imagination and reproduced by the media and the country’s institutions,” says Gil-Benumeya. Relegating the Andalusi period of Madrid to a “mere parenthesis” within Spanish history has resulted in a lack of general interest, he adds. Second, the visual clues that Al-Andalus ever existed are largely absent. In Cordoba and Granada to the south, the cities’ Islamic past are impossible to ignore or hide. That’s not the case in Madrid, where reminders are largely absent and you have to look for signs of its scant Andalusi heritage. To counter this, tours rely on narratives that bring the city’s hidden history to life. “

The centre in question promotes scientific research from historical and archaeological perspectives of medieval Islamic Madrid, and works to protect the city’s Islamic heritage. Underlying its work is the belief that a better understanding of Madrid’s Islamic past can contribute to inclusiveness and peaceful coexistence in the present.

It also testifies to the originality of this period in the history of the city, which succeeded, like other regions of al-Andalus, in bringing together the three great monotheisms in an almost perfect harmony never seen before.

Madrid, the small town madina sagira

In her book entitled: Madrid, petite ville de l’Islam médiéval (IXe-XXIe siècles), Christine Mazzoli-Guintard [ix] presents, from textual and archaeological sources, Madrid from its foundation to the present day. She argues that in order to understand the genesis of the city, it is necessary to return to the site where it was built, the name it received and the man who decided to build it. To understand its functioning, one must turn to its territories, nourishing and administrative, and to the spaces with which it is in contact. An Islamic legacy whose heritage recognition is still struggling, at the beginning of the 21st century, to be heard.

The first part of the work of Christine Mazzoli-Guintard begins with a description of the territory where the city was founded. The Guadarrama/Manzanares river is located far from the foundational settlement; nevertheless, its inhabitants counted on it for their supply, with a great network of springs and aqueducts from which it probably derived its name.

She dedicated a chapter to the analysis of the etymologies of the name Mayràé, for which she summarizes all that has been said previously. Referring to the debate on the Latin or Arabic origin of the name, she leaves the question open without opting for either option.

She devoted another chapter to the emir Muhammad I (852-886), founder of the city making a reference to Ibn Hayyan [x] who stated that it was this emir who ordered the creation of Madrid, Talamanca and Peñafora. Mazzoli-Guintard defined him as an “émir bâtisseur” by highlighting his construction activity.

To conclude this first part, she reviews the different hypotheses that have been proposed on the causes of the foundation of Madrid, Talamanca and Peñafora suggesting that it may have been related to the reorganization of the territory. At that time and within the framework of a centralizing policy, the creation of new cities was to be used to establish the basis for a stable administration of the entire Muslim Spain.

Outside the Andalusian enclosure, but in its immediate vicinity, archaeologists have located four zones in which wells and silos, later transformed into rubbish dumps, have been documented.

The second part, she points out that the founding of Madrid should be seen in the context of a general renewal of urban life in al-Andalus, from the foundation of Murcia (825) to that of Madînat az-Zahrâ’ (936).

With regard to the problem of the original walls, she makes a historiographic review of the studies carried out, in which two perimeters have been identified: the smaller one (4 Ha) has quadrangular towers and has been unanimously judged as an Andalusian work; the larger one (35 Ha), has quadrangular towers, as well, and has been considered by some as an Andalusian work and by others as a Christian factory. She adheres to the majority opinion that considers the Andalusian wall as the smaller one, while the larger one would be a Christian work.

Outside the Andalusian enclosure, but in its immediate vicinity, archaeologists have located four zones in which wells and silos, later transformed into rubbish dumps, have been documented. The material found inside them has been dated between the 9th and 11th centuries. With this scarce and imprecise information, the author excludes that they are remains of suburbs, leaning, rather, to identify them as belonging to settlements, contemporary to the foundation of the city and independent of it in origin.

Finally, she proposes that the city may have developed according to a settlement pattern similar to the one seen in Marroquíes Bajos (Jaén) and Pechina (Almería), which she believes was characteristic during the ninth and tenth centuries.

She argued that at the end of the ninth century, the progressive establishment of the Islamic state would be accompanied by this type of settlements where nuclei of houses grow around, but separate from, the fortified redoubt. The transformation of the silos into rubbish dumps would date them to this period and would be related to the beginning of the Umayyad taxes on agricultural incomes, a moment when, according to the author, the families’ need for storage decreases. This model would cease to function at the beginning the 11th century, when, with the fall of the caliphate, the classical model of the Andalusian medina appeared, where the majority of the population gathers within the walls. In this interpretative line, the historian defends a demographic growth of Madrid through population transfers to the city from nearby settlements.

The author offers the reader a valuable and precise monograph, always attentive to historiographical advances, which summarizes and combines the information one has on the city, enriching it through lively historical reflections. Mazzoli-Guintard interrogates and contrasts sources of different nature, fills the gaps of information by making opportune analogies with better known realities, always without forcing the data. Where she cannot contribute anything new, she gathers information that is always up to date with the most recent studies, offering in any case a useful re-reading and revision of the edited material.

The CEMI promotes scientific research from historical and archaeological perspectives of medieval Islamic Madrid, and works to protect the city’s Islamic heritage. Underlying its work is the belief that a better understanding of Madrid’s Islamic past can contribute to inclusiveness and peaceful coexistence in the present.

This work will be of interest to all those who want to approach the Islamic past of Madrid, be they specialists or simple amateurs; nevertheless, the methodology used is sufficiently good to serve as a model for other future research on the numerous Andalusian cities still pending study.

In a review of this highly-interesting work Juliette Sibon writes: [xi]

“Christine Mazzoli-Guintard, a specialist in Andalusian cities, places her study in the most recent field of urban history of al-Andalus, namely that of “small cities”. While much has been written about Madrid as a “border city,” the book considers Madrid as a “small city,” madina sagira, as described by al-Idrisi in the 12th century. Drawing on the many works devoted to the history of the city and on a large corpus of material and written sources, both Arab-Muslim and Christian, the author delivers a rigorous historical investigation that intertwines with a fine philological analysis, based on a solid knowledge of the language and Arabic texts. The method often consists in compensating for the absence of sources or their inconsistencies and inadequacies by returning to the Arabic terminology. The author gathers all the mentions of a term and tries to understand the use that the authors make of it in order to grasp the most accurate meaning possible. “

And goes on to say: [xii]

“The aim is to show how much Madrid, anchored in the Umayyad caliphate since 719, then in the taifa of Toledo (after 1009), before entering the Christian Castilian sphere (around 1085), was an actor in Andalusian history. The approach is clearly stated in the introduction: it is not a question of considering Madrid only as a “border city”, nor of considering the small city as a reduced model of the big city. It is therefore necessary to define another coherence, specific to the madina sagira. “

Madrid Today

The Madrid headquarters of Casa Árabe on Calle Alcalá, near the northern entrance to the Retiro, is a neo-Mudejar building constructed in 1886 that housed the Aguirre schools at the end of the 19th century.

This building was designed by the architect Emilio Rodríguez Ayuso, who conceived it as a two-story building capable of housing educational spaces that were particularly innovative for the time, including a gymnasium, a library, a school museum, a playground, a music room, and even a weather observatory located in the tower.

Casa Árabe, which is based in Córdoba and Madrid, is supported by various public institutions such as the Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation, the Autonomous Communities of Madrid and Andalusia, and the City Councils of Madrid and Córdoba.

Among the services offered is the restaurant-terrace “Acoge un Plato Casa Árabe”, whose gastronomic offer is part of the initiative “Acoge un Plato Catering”, of the Spanish Commission for Refugees (CEAR); a media library and a specialized bookstore for lovers of Arabic culture.

This tour of Medieval Madrid can be continued at the National Archaeological Museum, which includes an interesting collection of sumptuary arts from the Visigothic Kingdom of Toledo to the Late Middle Ages. The Medieval and Renaissance art rooms of the Museo Lázaro Galdiano and the Museo del Prado are also worth a visit. It is also worth mentioning the Christian Wall of Madrid which began to be built after the fall of Toledo during the reign of Alfonso VI of León and Castile (1040-1109) and continued its construction coinciding with the instability of borders and domains during the twelfth century and the first third of the thirteenth until 1212.

The National Archaeological Museum includes an interesting collection of sumptuary arts from the Visigothic Kingdom of Toledo to the Late Middle Ages.

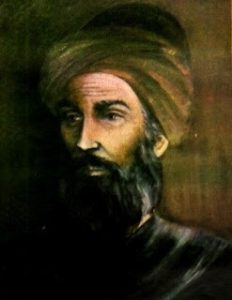

Among the luxury villas of a residential area in the north of Madrid is a small square with the mysterious name of Maslama. In fact, it is the only memorial in the city to one of its most famous sons: Abu Al-Qassim Maslama “Al-Majriti”, otherwise known as “the Madrilenian”.

Abû-l-Qâsim Maslama ibn Ahmad al-Faradi al-Hasib al-Qurtubi al-Majritî (Arabic: أبو القاسم مسلمة بن أحمد المجريطي), Arab mathematician, chemist, and astronomer from al-Andalus, born in Madrid in 950, died in 1007 in Cordoba, known as the master of mathematicians of al-Andalus. He lived mainly in Cordoba. [xiii]

He is quoted by Ibn Khaldun in his Muqaddima. He affirmed the law of conservation of matter. In astronomy, he translated and commented on the work of Ptolemy. He revised the Astronomical Tables of Al-Khwârizmî. [xiv] He was strongly inspired by the sciences in the civilizations of the ancient Greco-Roman world.

He published several works that have come down to us, including commentaries on al-Khwârizmî and books on geometry and arithmetic based on Greek and Hindu books.

He is credited with a treatise on astral magic, Ghâyat al-Hakîm (The End of the Sage) translated into Latin (by Gerard of Cremona?) under Alfonso X, king of Castile known as the Wise, (1221-1284) under the name of Picatrix, and dating from the middle of the eleventh century. [xv]

In today’s Madrid, he is a complete stranger, even to the inhabitants of the square that bears his name. In fact, it is difficult to find a list of illustrious Madrileños who predate the city’s Christian patron saint, San Isidro (Isidore the Ploughman), who according to legend was born at the end of the 11th century.

Conclusion: recuperating a long-forgotten past

On the idea of recuperating the long-forgotten past of Madrid, Daniel Gil-Benumeya, Scientific Coordinator of the Centro de Estudios del Madrid Islámico (CEMI) and professor of Arab and Islamic studies at Complutense University of Madrid, argues, quite rightly, in Orient XXI: [xvi]

“Throughout the last century, many vestiges of Andalusian Madrid have stubbornly reappeared, although they have not always been well treated: remains of the thousand-year-old wall, vestiges in the urban layout, archaeological materials related to daily life… Even a huge Muslim cemetery whose tenants are still there, looking towards Mecca from the foundations of the houses built over the graves when Islam and its sacred spaces formally disappeared in the 16th century. It is not marked and few people know of its existence, although it is the oldest cemetery in the city. “

And goes on to say: [xvii]

“Alongside the material remains, there is also a sometimes surprising intangible heritage. The name of Madrid’s Catholic patron saint, the Virgin of Almudena, comes from the Arabic name of the citadel that gave birth to Madrid: al-mudayna, “the little city” or “the citadel”. Even more surprisingly, recent research suggests that the patron saint, Isidore, a legendary character whose origin dates back to the time of the Christian conquest, is actually a syncretic character created from the memory of a Sufi murshid, Yunus Al-Azdi, who lived in the years before the conquest. “

The presence of the Arabs/Moors in Spain for 8 centuries is no doubt a painful history of colonization and Islamization of Christian land by force, but having said that it seems that this reality recedes when reflecting on this part of human history and, instead, several positive facts come to mind:

Al-Andalus permitted the advent of the only instance of coexistence of the three monotheisms in the history of humanity, referred to in Hispanic literature as convivencia. [xviii] Obviously many intellectuals reject this as a pure myth but the fact is that many others defend the veracity of this concept of vivre ensemble with as much strength for the simple reason that if this did not exist al-Andalus would not have been the cradle of fantastic development of human knowledge and wisdom; [xix]

Human experience in al-Andalus would not have been successful if it were not for the generosity of both the Spanish land, known as al-firdaws (among Arabs), and that of the Spanish people during Muslim rule;

This extraordinary development in thought and technology fed, undoubtedly, the European renaissance and led to the apogee of Western culture and way of life worldwide; and

Today with the revival of doubtful nationalisms and religious fundamentalisms reactivating sentiments of racism, xenophobia, hate, violence and intolerance, one wonders if it is not high time to go back to the spirit of forgiveness and conviviality of al-Andalus to root out the present atmosphere of dislike and anger directed at the other and his otherness.

Madrid, majra, majrit is about many sources and streams of wisdom and harmony much needed today. Madrid was a small town in the edge of al-Andalus in Spain. It is fully Spanish even in its Arab past and should be celebrated as such and must be fully recuperated for Spain and for humanity, especially at a time when hope for humanity, been humane and compassionate, is fading dangerously.

Yesterday, Madrid was a fortified edge of al-Andalus, today Islamic Madrid, with its many streams of consciousness, can surely become a world center of faith dialogue and intercultural dialogue. Amen.

*You can follow Dr. Mohammed Chtatou on Twitter: @Ayurinu

Endnotes:

[i] Chtatou, Mohamed. “ Ach-Charif al-Idrissi, concepteur de la première carte du monde, “Oumma du 8 juillet 2021. https://oumma.com/ach-charif-al-idrissi-concepteur-de-la-premiere-carte-du-monde/

[ii] Sampiro (c. 956 – 1041) was a Leonese cleric, politician, and intellectual, one of the earliest chroniclers of post-conquest Spain known by name. He was also the Bishop of Astorga from 1034 or 1035 until his death.

Cf. : Casado, Mar. Historia de El Bierzo (Algunos personajes bercianos. Sampiro.). Léon : Instituto de Estudios Bercianos, 1994.

[iii] Cressier, Patrice & Mercedes García-Arenal (Éd.). Genèse de la ville islamique en al-Andalus et au Maghreb occidental. Madrid, Casa de Velázquez, 1988.

[iv] Wasserstein, David J. The Caliphate in the West: An Islamic Political Institution in the Iberian Peninsula 1st Edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993.

This is a study of the caliphate as a political institution in Islamic Spain, from its inception in 316/939 until the disappearance of the Umayyads in Cordoba in 422/1031. David J. Wasserstein explores the caliphal claims of the Hammudid dynasty in the south of the peninsula, and examines the caliphal practices of two Slav rulers of the eleventh century. He shows that the caliphal insitution was not abolished at any stage, and that it served rulers throughout the eleventh century as, among other things, an important source of legitimacy. Wasserstein’s important new interpretation is thoroughly grounded not only in the documentary sources, but also in the little-studied and revealing numismatic evidence. This is a significant contribution both to the Islamic history of the Iberian Peninsula and to our understanding of the nature of the caliphate within Islam in general.

[v] Mazzoli-Guintard, Christine. “Conclusion,“in Madrid, petite ville de l’Islam médiéval (IXe-XXIe siècles). Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2009, pp. 221-225. https://books.openedition.org/pur/99057

“Quant au nom de la petite ville, Mağrīṭ, le débat sur l’origine latine ou arabe du toponyme reste ouvert ; latine pour les érudits du XIIIe siècle et jusqu’au milieu du XVIe siècle, arabe pour les savants du second XVIe siècle et jusqu’au XVIIIe siècle, à nouveau latine pour les lettrés du XIXe siècle, elle partage toujours les arabisants espagnols : aux tenants de la théorie arabe, développée par J. Oliver Asín et soutenue par Ma J. Rubiera Mata, s’opposent ceux de la thèse latine, développée par J. Coromines et suivie par F. Corriente et M. Marín. Le débat a toutefois oublié l’élément fondamental du peuplement du Madrid primitif, la présence des Berbères : installés dans la région au moment de la fondation, leur souvenir paraît avoir été totalement occulté par la décision émirale de fixer par un terme arabe, mağrā, le fil d’eau qui court, l’installation des hommes. “

[vi] Gil-Benumeya, Daniel. Madrid Islámico: La Historia Recuperada. Madrid: Balqis, 2021.

This work deals with the historical Islamic heritage of Madrid, from its foundation in the times of the Emirate of Al-Andalus, through the vicissitudes of the Mudejar Muslim community in medieval Christian Madrid, to the dawn of the Modern Age, when the last remnants of the Andalusian civilization were liquidated by the policy of cultural repression carried out by the Habsburgs.

The book thus covers almost 750 years of Islamic presence in Madrid, a heritage that has generally been little known and valued, except by specialists, due to several factors. The main one is undoubtedly the uninterrupted material and symbolic destruction of this legacy since Madrid became the seat of the Court in 1561. The capital of the Hispanic Monarchy first and of the Spanish nation later, could not easily assume its Islamic roots, given that in the Catholic and European identity definition that continues to be hegemonic in the Spanish imaginary. For this reason, Islam has been considered an unwanted presence or, in any case, a foreign one. Hence the subtitle La Historia Recuperada.

[vii] https://madridislamico.org/

El Centro de Estudios sobre el Madrid Islámico (CEMI):

Madrid is the only capital of Islamic origin in Europe. During its first two long centuries of existence, it was a small city of al-Andalus. And then, it maintained for more than five centuries a continued Islamic presence, through the Mudejar and Moorish minorities. This historical legacy is very little known, even among the Madrileños themselves, due to the blockages that exist to accept the legacy of al-Andalus as an integral part of Spanish history and culture, but also due to the bad inertias of heritage management.

For this reason, the Foundation for Islamic Culture/Fundación de Cultura Islámica (FUNCI) constituted in 2017 the Center for Studies on Islamic Madrid (CEMI).

It is an interdisciplinary space that aims to contribute to the knowledge and protection of the historical Islamic heritage of Madrid (Andalusian, Mudejar and Moorish). In a transversal way, CEMI wants to relate this legacy with the current construction of a diverse and respectful society in Madrid.

[viii] Walker, Kira. “The hidden Islamic history of Madrid revealed, “The Middle East Eye dated May 8, 2019. https://www.middleeasteye.net/discover/travel-madrid-hidden-islamic-history-revealed-spain-muslim-heritage

[ix] Mazzoli-Guintard, Christine. Madrid, petite ville de l’Islam médiéval (IXe-XXIe siècles). Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2009.

[x] Abū Marwān Hayyān Ibn Khalaf Ibn Hayyān (ابن حيان, Córdoba 987 – died 28 October 1076) was a famous Andalusian historian.

The son of an important bureaucrat of Almanzor, he was an official in the service of the Amiri dynasty. He wrote a number of historical works, preserved in part, which are one of the main sources for the study of the end of the Amiri dynasty (which led to the fall of the Caliphate of Cordoba and marked the beginning of the Taifa kingdoms). Like Ibn Hazm, he was a defender of the Umayyad dynasty, lamenting its fall and the consequent break with Andalusian centralism.

His two most important works were:

Kitâb al-Muqtabis (in 10 volumes),

Kitâb al-Matin (in 60 volumes).

These were two very important sources for historians; they relate events that took place mainly in Spain in the tenth and tenth centuries.

[xi] Sibon, Juliette. “Christine Mazzoli-Guintard, Madrid, petite ville de l’Islam médiéval (IXe-XXIe siècles)”, Cahiers de recherches médiévales et humanistes [Online], Reviews, Online since 30 November 2009, connection on 03 October 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/crm/11739; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/crm.11739

“Christine Mazzoli-Guintard, spécialiste des villes andalusi, inscrit son étude dans le champ le plus récent de l’histoire urbaine d’al-Andalus, à savoir celui des « petites villes ». Si beaucoup d’encre a coulé sur Madrid « ville-frontière », l’ouvrage envisage Madrid « petite ville », madina sagira, telle que la qualifie al-Idrisi au XIIe siècle. En s’appuyant sur les multiples travaux consacrés à l’histoire de la ville et sur un large corpus de sources matérielles et de sources écrites, tant arabo-musulmanes que chrétiennes, l’auteur livre une enquête historique rigoureuse qui s’entrecroise avec une analyse philologique fine, fondée sur une connaissance solide de la langue et des textes arabes. La méthode consiste souvent à pallier l’absence de sources ou leurs incohérences et insuffisances par un retour sur la terminologie arabe. L’auteur rassemble toutes les mentions d’un terme et tâche de comprendre l’utilisation qu’en font les auteurs afin d’en saisir l’acception la plus juste possible. “

[xii] Ibid.

“L’objectif est de montrer combien Madrid, ancrée dans le califat omeyyade dès 719, puis dans la taifa de Tolède (après 1009), avant d’entrer dans la mouvance de la Castille chrétienne (vers 1085), a été un acteur de l’histoire andalusi. La démarche est clairement exposée dans l’introduction : il s’agit de ne pas se cantonner à considérer Madrid seulement comme une « ville-frontière », ni de considérer la petite ville comme un modèle réduit de la grande ville. Il faut donc définir une autre cohérence, propre à la madina sagira. “

[xiii] Traité sur l’astrolabe, Translation in Spanish in J. Vernet et M.A. Catalá, “Las obras matemáticas de Maslama de Madrid”, in Al-Andalus, 30, 1965, pp. 15-45.

Cf. : Casulleras, Josep. “Abū al‐Qāsim Maslama ibn Aḥmad al‐Ḥāsib al‐Faraḍī al‐Majrīṭī , “ Thomas Hockey et al. (eds.) The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers, Springer Reference. New York: Springer, 2007, pp. 727-728. https://islamsci.mcgill.ca/RASI/BEA/Majriti_BEA.htm

Cf.: Samsó, Julio. Las ciencias de los antiguos en al‐Andalus. Madrid: Mapfre, 1992, pp. 80-110.

[xiv] Khuwārizmī, Muḥammad ibn Mūsá (813-846). The astronomical tables of al-Khwārizmi. Translation with commentaries of the Latin version edited by H. Suter, supplemented by Corpus Christi College MS 283, by O. Neugebauer. København : I kommission hos Munksgaard, 1962. https://www.royalacademy.dk/Publications/Low/736_Neugebauer,%20O.pdf

[xv] Fierro, Maribel. “Bātinism in al‐Andalus. Maslama b. Qāsim al‐Qurṭubī (d. 353/964), Author of the Rutbat al‐Ḥakīm and the Ghāyat al‐Ḥakīm (Picatrix).” Studia Islamica 63, 1986, pp. 87-112.

[xvi] Gil-Benumeya, Daniel. “La mémoire oubliée du Madrid musulman, “Orient XXI du 3 septembre 2021. https://orientxxi.info/magazine/la-memoire-oubliee-du-madrid-musulman,5003

“ Tout au long du siècle dernier, de nombreux vestiges du Madrid andalou sont réapparus avec obstination, même s’ils n’ont pas toujours été bien traités : restes de la muraille millénaire, vestiges dans le tracé urbain, matériaux archéologiques liés à la vie quotidienne… Jusqu’à un immense cimetière musulman dont les locataires sont toujours là, regardant vers La Mecque depuis les fondations des maisons construites sur les tombes lorsque l’islam et ses espaces sacrés ont formellement disparu au XVIe siècle. Il n’est pas signalé et peu de gens connaissent son existence, bien qu’il s’agisse du plus ancien cimetière de la ville. “

[xvii] Ibid.

“Aux côtés des vestiges matériels, il existe aussi un patrimoine immatériel parfois surprenant. Le nom de la patronne catholique de Madrid, la Vierge de l’Almudena, vient du nom arabe de la citadelle qui a donné naissance à Madrid : al-mudayna, « la petite ville » ou « la citadelle ». Plus étonnant encore, des recherches récentes suggèrent que le saint patron, Isidore, personnage légendaire dont l’origine remonte à l’époque de la conquête chrétienne, serait en réalité un personnage syncrétique créé à partir de la mémoire d’un murshid soufi, Yunus Al-Azdi, ayant vécu dans les années précédant la conquête. “

[xviii] Convivencia (Spanish, from convivir, “to live together”, “convivence”) is a concept that was used by historians of Spain in the twentieth century, but was much debated as anachronistic and then abandoned by most in the twentieth century, It refers to a period in the medieval history of the Iberian Peninsula (and in particular of al-Andalus) during which Muslims, Jews and Christians coexisted in a state of relative confessional peace and religious tolerance, and during which cultural exchanges were numerous.

This concept was first put forward by Américo Castro to describe the relations between Christians, Jews and Muslims in the peninsula during the Hispanic historical period, which runs from the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 until the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492 after the end of the Reconquista. Castro presents this period as a “stabilized pluralism” in which exchanges and dialogues would have enriched groups of different obedience, having essentially peaceful relations, and affirms that it is this conjunction that favors the cultural development of the peninsula.

Cf. Connie Scarborough, Revisiting Convivencia in Medieval and Early Modern Iberia, Juan de la Cuesta, coll. « Hispanic Monographs / Estudios de literatura medieval » (no 11), 2014.

[xix] Chtatou, Mohamed. “Al-Andalus: Multiculturalism, Tolerance and Convivencia, “FUNCI dated May 11, 2021. https://funci.org/al-andalus-multiculturalism-tolerance-and-convivencia/?lang=en

Arab references:

Crónica anónima de `Abd al-Raḥmān III al-Naṣīr, éd. E. Lévi-Provençal et E. García Gómez, Madrid-Granada, CSIC, 1950.

Ḏikr, Una descripción anónima de al-Andalus, éd. et trad. L. Molina, Madrid, CSIC, 1983.

al-Ḍabbī, Aḥmad b. Yaḥyā

Buġyat al-multamis fī ta`riḫ riğāl ahl al-Andalus, F. Codera et J. Ribera (éd.), Madrid, Josephum de Rojas, 1885.

al-Fārābī, Abū Naṣr

La ciudad ideal, trad. M. Alonso Alonso, Madrid, Tecnos, 1985 (publication initiale dans la revue al-Andalus, 1961-26 et 1962-27).

al-Ḥimyarī, Ibn `Abd al-Mun’im

La péninsule ibérique au Moyen Âge d’après le Kitāb ar-Rawḍ al-mi`ṭār, trad. É. Lévi-Provençal, Leiden, Brill, 1938 ; Kitāb al-Rawḍ miṭ`ār, Iḥsān `Abbās (éd.), Beyrouth, Dār al-Ğīl, 1988.

Ibn al-Abbār, Muḥammad b. `Abd Allāh

Kitāb al-takmila li-Kitāb al-ṣila, F. Codera (éd.), Madrid, Josephum de Rojas, 1887-1889; M. Alarcón et A. González-Palencia (éd.), Miscelánea de Estudios y Textos Árabes, Madrid, 1915, p. 147-690; A. Bel et M. Ben Cheneb (éd.), Alger, Imprimerie Orientale, 1920; `A. al-S. al-Harrā s (éd.), Casablanca, Dār al-ma`rifa, s.d., 4 vol.

Ibn `Abdūn, Muḥammad b. Aḥmad

Séville musulmane au début du XIIe siècle, Le traité d’Ibn `Abdūn sur la vie urbaine et les corps de métiers, trad. É. Lévi-Provençal, Paris, G.P. Maisonneuve, 1947.

Ibn Abī Zar`, Abū l-`Abbās Aḥmad al-Fāsī

Rawḍ al-Qirṭās, trad. A. Huici Miranda, Valencia, [Anúbar], 1964.

Ibn Bassām al-Šantarinī, `Alī

Al-Ḏaḫīra fī maḥāsin ahl al-Ğazīra, Iḥsān `Abbās (éd.), Beyrouth, Dār al-ṯaqāfa, 1979, 8 vol.

Ibn Baškuwāl

Kitāb al-ṣila fī ta’rīḫ a`immat al-Andalus, F. Codera (éd.), Madrid, Josephum de Rojas, 1883.

Ibn al-Faraḍī, `Abd Allāh b. Muḥammad

Ta’rīḫ `ulamā’al-Andalus, F. Codera (éd.), Madrid, Typographia La Guirnalda, 1891-1892.

Ibn Ḥayyān al-Andalusī

Crónica de los emires Alḥakam I y `Abdarraḥmān II entre los años 796 y 847 (Al-Muqtabis II-1), trad. M. `Alī Makkī et F. Corriente, Zaragoza, Instituto de Estudios Islámicos del Oriente Próximo, 2001 ; J. Vallvé Bermejo (éd.), Madrid, Real Academia de la Historia, 1999.Kitāb al-muqtabis fī ta’rīḫ riğāl al-Andalus, t. II, M. `Alī Makkī (éd.), Beyrouth, Dār al-Kitāb al-`arabī, 1973.

Crónica del califa `Abdarraḥmān III an-Nāṣir entre los años 912 y 942 (Al-Muqtabis V), P. Chalmeta, F. Corriente et M. Ṣubḥ (éd.), Madrid, Instituto Hispano-Árabe de Cultura, 1979 ; trad. Ma J. Viguera et F. Corriente, Zaragoza, Instituto Hispano-Árabe de Cultura, 1981.

Anales palatinos del califa de Córdoba Al-Ḥakam II, por `Īsā ibn Aḥmad al-Rāzī, trad. E. García Gómez, Madrid, Sociedad de Estudios y Publicaciones, 1967.

Ibn Ḥazm

Naqṭ al-`arūs, trad. L. Seco de Lucena, Valencia : [Anúbar], 1974.

Ibn `Iḏārī al-Marrakušī

Kitāb al-Bayān al-Muġrib, G. S. Colin et É. Lévi-Provençal (éd.), Leiden, Brill, 1951, t. II ; Histoire de l’Afrique et de l’Espagne intitulée Al-Bayano’l-Mogrib, trad. E. Fagnan, Alger, Imprimerie Orientale Pierre Fontana, 1904, t. II.

La caída del califato de Córdoba y los Reyes de taifas, trad. F. Maíllo Salgado, Salamanca, Universidad de Salamanca, 1993 ; É. Lévi-Provençal (éd.), Paris, Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 1930.

Ibn Ḫaldūn

Discours sur l’Histoire universelle, Al-Muqaddima, trad. V. Monteil, Arles, Actes Sud, 1997.

Ibn al-Ḫaṭib, Lisān al-Dīn

Al-ihāṭa fī aḫbār Ġarnāṭa, M. `Abd Allāh `Inān (éd.), Le Caire, Dār al-Ma`ārif, 1955.

Ibn al-KardAbūs, `Abd al-Malik

Kitāb al-iktifā’fī aḫbār al-ḫulafā’(Libro de lo suficiente acerca de las noticias de los califas), éd. de la partie relative à al-Andalus par A. M. al-`Abbādī, Revista del Instituto de Estudios Islámicos, 1965-66 (XIII), p. 7-126 ; trad. F. Maíllo Salgado, Madrid, Akal, 1986.

Ibn Sa`īd, `Alī b. Musā

Al-Muġrib fī hulā al-Maġrib, Šawqī Ḍayf (éd.), 2 vol., Le Caire, Dār al-Ma`ārif, 1953-1955.

al-Idrīsī, Muḥammad b. Muḥammad al-Šarīf

Opus geographicum, fasc. 5, E. Cerulli, F. Gabrielli, G. Levi della Vida, L. Petech, G. Tucci (éd.), Napoli-Roma, Istituto Univesitario Orientale di Napoli-Istituto Italiano per il medio ed estremo Oriente, 1975.

Description de l’Afrique et de l’Espagne, trad. R. Dozy et M. J. de Goeje, Leiden, E. J. Brill, 1866 (réimp. 1968).

La première géographie de l’Occident, trad. du chevalier Jaubert présentée par H. Bresc et A. Nef, Paris, Flammarion, 1999.

Los caminos de al-Andalus en el siglo XII según Uns al-Muhaŷ wa-Rawḍ alfuraŷ, J. Abid Mizal (éd. et trad.), Madrid, CSIC, 1989.

al-Maqqarī, Aḥmad b. Muḥammad

The History of the Mohammedan dynaties in Spain, trad. P. de Gayangos, London, The Oriental Traslation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland, 1840, rééd. London, Routledge Curzon, 2002.

al-Marrākušī, Ibn `Abd al-Malik

Al-Ḏayl wa-l-takmila, Iḥsān `Abbās (éd.), Beyrouth, Dār al-Ṯaqāfa, 1964-1973.

al-Marrākušī, `Abd al-Wāḥid

Al-Mu`ğib fī talḫī aḫbār al-Maġrib, M. S. al-`Aryān et M. al-`Arabī al-`Alamī (éd.), Casablanca, Dār al-kitāb, 7e éd., 1978.

Al-Rāzī, Aḥmad b. Muḥammad b. Musā

« La description de l’Espagne d’Aḥmad al-Rāzī. Essai de reconstitution de l’original arabe et traduction française », par É. Lévi-Provençal, Al-Andalus, 1953 (18), p. 51-108.

Crónica del moro Rasis, D. Catalán et Ma S. Andrés (éd.), Madrid, Gredos, 1975.

Ṣā`id b. Aḥmad al-Andalusī

Kitāb Ṭabaqāt al-umam (Livre des catégories des nations), trad. R. Blachère, Paris, éd. Larose, 1935 ; Libro de las categorías de las naciones : vislumbres desde el Islam clásico sobre la filosofía y la ciencia, trad. F. Maíllo Salgado, Madrid, Akal, 1999.

al-`Umarī, Ibn Fadl Allāh

Masālik al abṣār fī mamālik al-amṣār, t. 1, L’Afrique, moins l’Égypte, trad. M. Gaudefroy-Demombynes, Paris, Librairie Orientale Paul Geuthner, 1927.

al-Wanšarīsī, Aḥmad b. Yaḥyā

Histoire et société en Occident musulman au Moyen Âge, Analyse du Mi`yār d’al-Wanšarīsī, par V. Lagardère, Madrid, Casa de Velázquez-CSIC, 1995 ; M. Ḥağğī (éd.), Rabat, Wizārat al-awqāf wa-l-šu`ūn al-islāmiyya, 1981-1983.

Watwāt, Muḥammad b. Ibraḥim

Menâhidj el-fiker, trad. E. Fagnan, Extraits inédits relatifs au Maghreb, Alger, 1924.

Yāqūt al-Rumī

Mu`ğam al-buldān, éd. Le Caire, 1906 ; trad. G. `Abd al-Karīm, « La España musulmana en la obra de Yāqūt (s. XII-XIII). Repertorio enciclopédico de ciudades, castillos y lugares de al-Andalus, extraído del Mu`ŷam al-buldān (Diccionario de los países) », Cuadernos de Historia del Islam, 1974 (6).