Articles

The hidden Islamic history of Madrid revealed

Article theme: Al-Andalus, History, Madrid, Tourism.

We portray underneath a brief story on the Islamic origins of Madrid published by reporter Kira Walker for the Middle East Eye. The report gathers statements from the main activists on the promotion of Madrid’s Muslim heritage, including Encarna Gutiérrez, Secretary General of FUNCI, and Daniel Gil-Benumeya, Scientific coordinator of the Centre for the Study of Islamic Madrid.

Hachim Oulad Mhammed was reading an Arabic book on ancient history when he first learnt that Madrid had Islamic origins. It piqued his curiosity and he began investigating. What he found was, at first, striking: now it evokes pride, weighed down by sadness. Spanish society, as a whole, says Oulad Mhammed, 36, a Madrid community activist, doesn’t know much, if anything, about the city’s Islamic heritage.

“The past was much more diverse than people can imagine,” he says. “It was not all conflict and bloodshed. “It was also a period of cooperation, commerce, and a lot of interesting things that are not very present in the collective imagery that Spanish people have of Al-Andalus.”

Mayrit: A little-known history

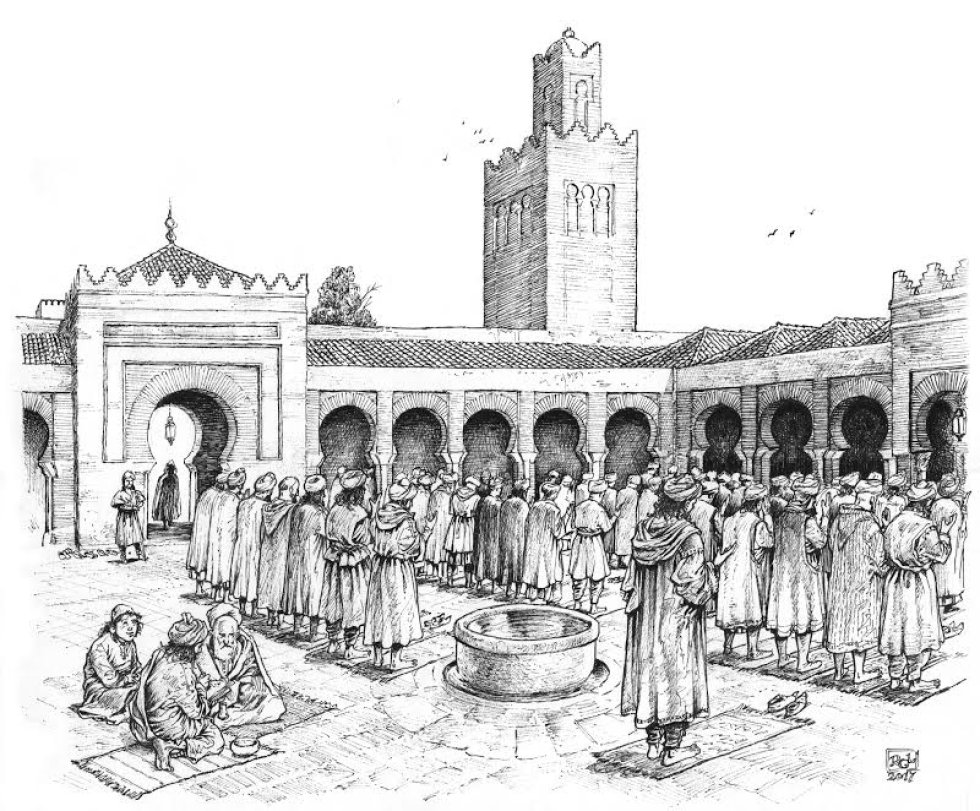

Al-Andalus was the territory under Muslim rule for more than seven centuries, from 711 and 1492. At its greatest extent, it covered most of the Iberian Peninsula, including modern-day Spain and Portugal.

Founded around 865 by Umayyad emir Mohamed I, Mayrit – as Madrid was first known – was one of a chain of fortified military enclaves along the frontier between Muslim Al-Andalus and the Christian kingdoms to the north.

The city was named after the subterranean water channels – the Arabic word is mayra – that Mohamed I ordered to be constructed. In the late 11th century, Christians conquered Mayrit, although a sizeable Muslim population continued to live in the city until the expulsion of Spain’s Muslims in 1609.

The capital is now home to an estimated 300,000 Muslims. Spain’s Muslim population has grown to around two million in recent decades due to migration, with most coming from Morocco, along with others from Algeria, Nigeria, Senegal and Pakistan. Many eventually go on to become Spanish citizens.

La Moreria, the quarter where Muslims lived following the Christian conquest, is now a vibrant neighbourhood, a maze of narrow, winding streets full of terraces, tapas bars, cafes, restaurants, and the city’s oldest churches and museums. The Royal Palace, for example, stands on the site of the Moors’ ninth-century Alcazar (citadel), which was destroyed by fire in 1734.

For Madrileno Aurora Ali, 39, spokesperson for the Madrid-based Muslim Association for Human Rights, restoring the historical memory of the city’s Islamic origins is a cause of joy and optimism.

“We are here. We see it in the architecture, but we are somehow not acknowledged, and we’re treated as foreigners, so this is a really nice counter-narrative,” she says.

The influence of the Muslim founders is hinted at in the city’s oldest standing mudejar buildings and the vestiges of a ninth-century wall preserved in a quiet park named after the city’s first ruler, Parque Mohamed I. The mudejar style is a cultural hybridisation that incorporates Islamic tradition and Moorish influences and decorative elements into European architectural styles, characterised by its refined brickwork and glazed tiles.

But otherwise, few visible clues remain of the city’s Muslim past.

Recovering the past

Efforts to recover and safeguard the city’s Islamic heritage have intensified in recent years, largely under the direction of Spain’s Islamic Culture Foundation (FUNCI).

Encarna Gutierrez, the foundation’s secretary general, says it was developed in the belief that Spain needed to embrace its multi-cultural heritage, and that education needed to play a part in this cultural acknowledgement.

In 2017, the foundation partnered with the Complutense University of Madrid to establish the Centre for the Study of Islamic Madrid (CEMI).

The centre promotes scientific research from historical and archaeological perspectives of medieval Islamic Madrid, and works to protect the city’s Islamic heritage. Underlying its work is the belief that a better understanding of Madrid’s Islamic past can contribute to inclusiveness and peaceful coexistence in the present.

“The less knowledge people have, the easier it is to manipulate it, and the easier it is to see other cultures and religions as foreign elements, instead of as an essential part of our history,” says Gutierrez.

“The rejection of Islam in Spain can mainly be explained by the lack of knowledge people have towards this topic.”

Daniel Gil-Benumeya, the scientific coordinator at CEMI, explains that it offers guided visits to different Islamic “places of memory” – sites across Madrid where there aren’t always visible historical remains, but which hold special significance for its Islamic heritage.

The centre is also launching a series of lectures in collaboration with the Museum of San Isidro. It will soon offer workshops and activities on aspects of Madrid’s Andalusi heritage including gastronomy, gardening, ceramics and archaeology.

Myths and invented history

That the Islamic history of Madrid remains so little known to this day is down to two key reasons. The first, says Gil-Benumeya, is that the city is the capital of Spain, encapsulating the idea of the imagined Spanish community – which is Catholic and European – and all its myths.

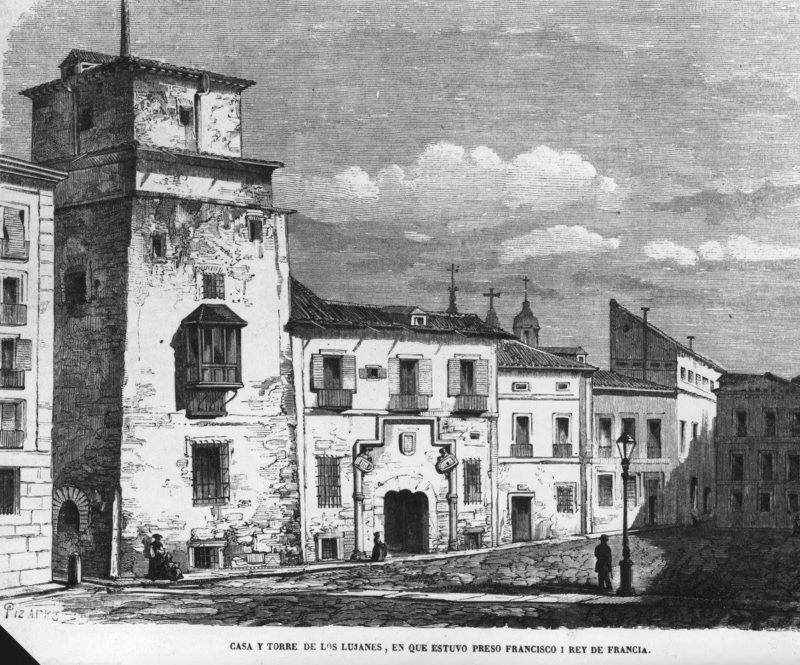

He explains that in 1561, King Felipe II made Madrid the permanent seat of his court: soon after the city’s material and symbolic medieval past were erased to build a capital worthy of the growing empire.

Part of this process involved inventing several heroic myths relating to Madrid’s history – but in doing so the city’s Islamic origins were radically suppressed.

“This narrative cannot be defended from a scientific point of view, but is deeply rooted in the popular imagination and reproduced by the media and the country’s institutions,” says Gil-Benumeya.

Relegating the Andalusi period of Madrid to a “mere parenthesis” within Spanish history has resulted in a lack of general interest, he adds.

Second, the visual clues that Al-Andalus ever existed are largely absent. In Cordoba and Granada to the south, the cities’ Islamic past are impossible to ignore or hide. That’s not the case in Madrid, where reminders are largely absent and you have to look for signs of its scant Andalusi heritage. To counter this, tours rely on narratives that bring the city’s hidden history to life.

Mistrust to acceptance

The city administration’s approach to Madrid’s neglected Islamic origins have changed markedly in recent years.

Following the 2015 election of a leftist coalition to run Madrid’s council after 24 years of uninterrupted conservative rule, the new administration has been more sympathetic towards FUNCI and its efforts to highlight the city’s Islamic past.

Recent years have also seen a rapid growth in halal tourism, offering opportunities for Madrid’s government as well as the private sector.

In 2014, journalist Rafael Martinez started offering guided walking tours of Madrid’s Islamic history and has watched interest in this period of history grow steadily ever since.

The tours were a natural evolution from the website he created to make the Andalusi history of Madrid accessible to an audience outside academia.

“I began to receive many requests for visits to show what I was writing about. The growing interest and curiosity of people to know their roots were key.” Through the tours, Martinez hopes to contribute to the recognition and normalisation of the Andalusi legacy of Madrid. Most of Martinez’s clients are Madrilenos, though interest among foreigners and Spanish Muslims outside the capital is increasing.

People who take his tours, he says, tend to sympathise with the Arab and Islamic world, have travelled through Muslim majority countries and are keen to learn about the Islamic origins of Spain’s largest city.

Most foreign Muslims, he says, know Madrid only as a destination for football and shopping and are not aware of its past at the outset.

Flora Saez, co-founder of the Madrid-based halal tourism agency Nur & Duha Travels, is looking to change that. She says they always begin tours of Madrid with a visit to its Islamic vestiges. “It would be inconceivable for us to not make Madrid known from this perspective.”

Despite lacking impressive monuments to Al-Andalus, Saez says visitors are still drawn to learn about this side of the city. Discovering the traces of Islam in some of the most emblematic places of Madrid, such as the Plaza de la Villa, is, Saez adds, an apt reminder that Al-Andalus was much wider than present-day Andalusia.

Look to the past for the future

As the far-right and Islamophobia continue to gain traction in Spain and around the world, Gutierrez says FUNCI considers its efforts more necessary than ever. “We need to embrace our past and be proud of it.”

Gil-Benumeya concurs, and says the wide and deeply rooted array of Islamophobic stereotypes in Spanish society makes it easy for the far-right to rely on a certain version of Spain’s medieval history for populist purposes. “The ‘Moor’ is the biggest ‘other’, but it is also part of ‘us’,” he says.

In this context, creating the space to talk about Madrid’s Islamic past and giving its heritage its rightful place in history are positive steps forward.

Ali says: “There’s a lot of civil society that does want the truth, that does want to know where they come from, and that are open to all of this.” Ali thinks the efforts will have an impact on prevailing prejudice and also points to what such efforts could mean for Madrid’s Muslim community.

“This will be comforting for the Muslims that are here because at some point, we might not be seen as the foreigners.”

Source: Middle East Eye