Articles

The emergence of the Rihla or travel literature

Article author: Alfonso Casani

Date of publication of the article: 23/02/2021

Year of publication: 2021

Article theme: Al-Andalus, History, Islam, Literature.

“Travelling – it leaves you speechless and then turns you into a storyteller”, Ibn Battuta

Among the many literary styles that flourished throughout the Middle Age we can highlight, due to its prominence and later importance, the rihla or travel literature, which emerged from the 12th onwards in Al-Andalus and the North of Africa. The rihla reached its peak with the works of Ibn Jubayr, who institutionalized the genre, and, especially, the well-known traveler Ibn Battuta. This genre did not only have a great artistic value, it also served as a description and analysis of the times these travelers lived, contributing to our current understanding of the times.

Developed between the 12th and 14th century, these travels took place at a moment when the Mediterranean was interconnected, facilitating the mobility of its inhabitants across the region, from Al-Andalus to the Abbasid caliphate, but also through the Christian territories such as Sicily or the Jerusalem visited by Ibn Jubayr. These new mobility opportunities allowed for the development of two common types of travel among the Muslim elites: the travel for scientific education, and the pilgrimage to Mecca, according to the five pillars of Islam. Usually, one and the other overlapped and were complemented with the wish for geographical and mathematician knowledge, and the development of authentic autobiographic stories. Thus, travel stories offered a compilation of details on geographical and sociological elements observed by the traveler, gave an account of their encounters and the scientific and religious developments, and told the adventures and experiences lived by the travelers abroad.

The rihla or travel literature was the expression of a geographical literary genre previously developed, which gained a greater literary value with the passing of time. This type of literature developed since the 9th century, in the form of administrative briefs for public servants, and evolved throughout the centuries to more complex technical works, such as geographic dictionaries or universal encyclopedias and cosmographies, as the ones published by al-Mas’udi (956) and al-Biruni (1048). These works evolved into the rihla, where the traveler, aware of the importance of his spiritual and educational travel, tells his experiences and observtions in his way to Mecca or to knowledge centers such as Baghdad.

These new mobility opportunities allowed for the development of two common types of travel among the Muslim elites: the travel for scientific education, and the pilgrimage to Mecca, according to the five pillars of Islam.

Ibn Jubayr, the first Rihla

The mergence and spreading of the Rihla can be attributed to Abu al-Husain Muhammad Ibn Ahmad Ibn Jubayr al-Kinani al-Andalusi al-Balansi, known as Ibn Jubayr, born in Valencia in the year 1145 (thus his alias, “al-Balansi”, the “Valencian”) and died in Alexandria in 1217. Born into a wealthy family, Ibn Jubayr worked as the secretary of the governor of Granada, Abu Sa‘id ‘Uthman b. ‘Abd al-Mu’min.

Ibn Jubayr’s journey begins with his search for atonement. As explained by Ibn Jubayr in his work “Travels”, which tells his travel to Mecca between the years 1183 and 1185, his decision to embark himself in the hajj began when the Governor, insulted by his Ibn Jubayr’s rejection to share a glass of wine with him, forced him to drink seven cups. In compensation, the Governor gave him seven cups filled with gold, which granted our traveler the means to go to Mecca and amend the sin committed.

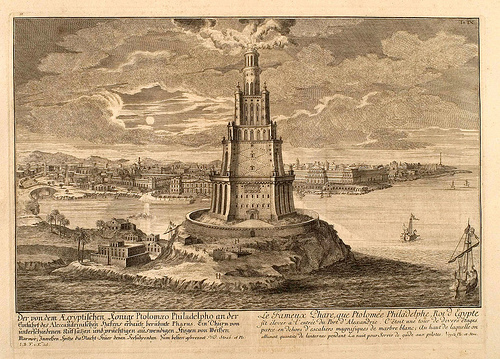

Throughout his journey, Ibn Jubayr crossed the Mediterranean and visited Egypt, from where he moved to Mecca. He also visited Syria, Iraq, Palestine, Sardinia, Sicily, and Greece. With an objective and detailed look, Ibn Jubayr described the political situation of the Middle East during his two years of travels and the changes that were taking place in the region, such as the decadence of the Abbasid caliphate, the restitution of Sunnism, and the rise of Saladin. in the context of the crusades, Ibn Jubayr explains the impact of the loss and decadence of Muslim territories (on Baghdad, for instance, he states: “Most of its traces have gone, leaving only a famous name”), he described the Normand Sicily (of King William II he said: “He has much confidence in Muslims,” he wrote, “relying on them for his affairs … in them shines the splendor of his realm”, and the many encounters he had with the Christian population.

On Baghdad, for instance, he states: “Most of its traces have gone, leaving only a famous name”.

Ibn Battuta, the traveler par excellence

Undoubtedly, the most well-known Muslim travel, Ibn Battuta was born in Tangier in 1304, and spent a third of his life travelling. His first and loner journey, which lasted 24 years, was portrayed by poet Ibn Juzzay in the work “A Masterpiece to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling” (known as the “Rihla”), which became this literary genre’s work par excellence, and enshrined Ibn Battuta as one of the most important travelers of the Middle Age.

Undoubtedly, the most well-known Muslim travel, Ibn Battuta was born in Tangier in 1304, and spent a third of his life travelling. His first and loner journey, which lasted 24 years, was portrayed by poet Ibn Juzzay in the work “A Masterpiece to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling” (known as the “Rihla”), which became this literary genre’s work par excellence, and enshrined Ibn Battuta as one of the most important travelers of the Middle Age.

We barely have any more biographical data of Ibn Battuta than that portrayed in this work. This has contributed to the romanticization of his life, through a work that takes many creative licenses. In this light, Ibn Battuta’s work accords a lot of importance to the artistic and literary element, distancing itself from previous works. In spite of this, his travels, commissioned by Morocco’s Marinid Sultan Abu Inan with the aim of gathering geographical, political and cultural information on the region, are a relevant source of descriptions on the 14th century’s political and social context, of immeasurable historic importance.

Through his quarter of a century-long journey, Ibn Battuta visited Al-Andalus and the current territories of Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman, Turkey, the South of Russia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Indonesia, and Mali. His visits offer a vivid testimony of the decline of Al-Andalus, of Genghis Khan’s progress across Central Asia and the Middle East, or the prosperity of the Maldives.

The Mudejar rihla, Omar Patun’s journey

Three decades ago, an important discovery and contribution to the literary genre of the rihla was made in Calanda (Teruel, north of Spain). It is this genre’s only work from the Christian kingdom of Castille. The manuscript is attributed to a Moorish traveler and it is written in aljamiado (Spanish language with Arabic letters). The document was found hidden in under a house in a working construction, along with eight other manuscripts who, it is believed, were hidden by some Moorish faqih to avoid their interception by the Inquisition. In addition to the literary importance of this work, the discovery shows the efforts of preservation of Islam and Muslim culture by the Muslim population living under Christian sovereignity.

Three decades ago, an important discovery and contribution to the literary genre of the rihla was made in Calanda (Teruel, north of Spain). It is this genre’s only work from the Christian kingdom of Castille. The manuscript is attributed to a Moorish traveler and it is written in aljamiado (Spanish language with Arabic letters). The document was found hidden in under a house in a working construction, along with eight other manuscripts who, it is believed, were hidden by some Moorish faqih to avoid their interception by the Inquisition. In addition to the literary importance of this work, the discovery shows the efforts of preservation of Islam and Muslim culture by the Muslim population living under Christian sovereignity.

His rihla tells Omar Patun’s hajj in the year 1481. In the company of a second Castilian Muslim, Mohamed del Corral, his journey lasted four years, after they missed their boat towards the Iberian Peninsula in Egypt, where they were forced to stay for a year.

When they returned, their adventures were registered on their way across Teruel. Even though the manuscript is not in very good condition, partially damaged by humidity and the passing of time, it is believed that it was not written by a professional scribe, nor by Omar Patun himself. Taking into account the manuscript’s style and handwriting, two hypothesis seem feasible: that the manuscript is a copy of the original, made by some Muslim during their scale on Teruel, or that the manuscript was written while the travelers described their experiences orally.

In any case, this work is an important diary of the Mediterranean world in the 15th century, through which Omar Patun describe the Iberian Peninsula, Tunisia, Greece, Turkey, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and, finally, Jeddah and Mecca.