Articles

Sea of Tears, an exhibition to the migrants lost in the sea

Article author: Juliet Highet

Date of publication of the article: 24/01/2022

Year of publication: 2021

Article theme: Art, Exhibitions, Fotografía, Inmigration.

We reproduce the article “Sea of Tears, Garden of Memory”published on the AramcoWorld’s latest issue. Written by Juliet Highet, all photos belong to Rachid Koraïchi, artist and producer of the exhibition.

The exhibition of sculpture, calligraphy and ceramics was shown in London, and the cemetery—owned, designed and built by Koraïchi—lies on the outskirts of the town of Zarzis, in southern Tunisia, along the shore of the Mediterranean Sea. Both exhibition and cemetery are characterized by migration, memory and mourning as well as empathy, dignity and peace.

The exhibition of sculpture, calligraphy and ceramics was shown in London, and the cemetery—owned, designed and built by Koraïchi—lies on the outskirts of the town of Zarzis, in southern Tunisia, along the shore of the Mediterranean Sea. Both exhibition and cemetery are characterized by migration, memory and mourning as well as empathy, dignity and peace.

The Garden of Africa opened on June 9, 2021, as a charitable burial ground, a creatively designed final resting place for some of the hundreds of refugees and migrants whose fates in the nearby waters have become known only when sea currents, which are particularly strong around Zarzis, have carried their bodies to the shore. The Garden of Africa is therefore “a place of remembrance, filled with fragrant plants that recall Paradise as described in the Qur’an,” says Koraïchi.

Attending the opening ceremony at the invitation of Tunisian President Kais Saied, UNESCO Director-General Audrey Azoulay afterward stated on Twitter that Koraïchi’s initiative “offers beauty to those who did not have a grave. His gesture testifies to our common humanity and says that everyone has the right to this dignity.” According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), in 2020 more than 1,000 people drowned attempting to cross the Mediterranean from North Africa to Europe. Azoulay and Koraïchi were joined at the ceremony by representatives of the country’s three major historic faith traditions of Islam, Christianity and Judaism to emphasize the nonsectarian, humanitarian mission of the project. Azoulay also presented a bronze sculpture called The Tree of Peace.

Both exhibition and cemetery are characterized by migration, memory and mourning as well as empathy, dignity and peace.

The cemetery is set in an olive orchard, into which one enters this “paradise,” as Koraïchi calls it, through a gate painted brilliant yellow, representing the intensity of the African sun. The gate intentionally offers a low portal so that each visitor must stoop to pass through in a gesture of deference to those who took to sea in the hope of a brighter future that never came.

Two large alabaster stelae, which stand one on either side of the gate, serve as “symbolic, talismanic guardians of those who pray for the dead,” says Koraïchi, referring to the families and friends of those lost. The stelae replicate ones used by the artist’s family, whose lineage goes back to descendants of the Prophet Muhammad and who themselves migrated to North Africa via Kairouan, which they helped found in today’s Tunisia, some 350 kilometers north of Zarzis, and eventually settled farther west in Algeria.

From the gate, paths paved with antique ornamental tiles from Nabeul, the Tunisian town long famous for ceramic designs, line rows of burial plots. The paths are bordered by aromatic, therapeutic herbs such as algave, aloe vera and calendula, together with fragrant flowers such as jasmine, night-blooming cacti and red bougainvillea. Bitter oranges have been planted to symbolize both the hardship of death and the sweetness of the afterlife. Five olive trees have been designated to represent Islam’s five pillars, and similarly, 12 vines represent the 12 disciples of Jesus. The central path leads to a domed room dedicated to interfaith prayer and reflection.

The Garden of Africa has its origin in 2018, when Koraïchi’s daughter Aicha read on social media that Mediterranean currents had been washing an unusual number of bodies onto beaches around Zarzis, and that many were not receiving burials. Daughter and father visited Zarzis later that year, and what they found saddened them deeply. “I couldn’t stand the thought that people fleeing poverty, climate change, war and Covid were ending up in landfill. I wanted them to rest in an honorable place,” Koraïchi comments. In addition, the experience evoked the grievous personal loss of Koraïchi’s elder brother Mohammed, who in 1962 was swept to sea by a rip tide and never found.

“I couldn’t stand the thought that people fleeing poverty, climate change, war and Covid were ending up in landfill. I wanted them to rest in an honorable place.”

Koraïchi took initiative as both a humanitarian and an artist. “I bought land there, a 2500-square-meter plot to turn into a cemetery: The Garden of Africa. It’s a huge task, which I’m funding myself, with no governmental help,” Koraïchi says. This has included not only planting, building and decorating, but also raising the ground level so that graves, when dug, would not reach the water table. For each refugee who is buried, the small staff at The Garden of Africa obtains and keeps a record of a DNA sample “in the hope that one day we may be able to identify them through DNA provided by relatives,” he explains. Building this haven and covering its operating expenses, including salaries for employees such as a live-in guardian and gravediggers, Koraïchi emphasizes, “is like offering a gift to a loved one. It’s not the price that matters. It is how much you want to offer the gift.”

The Tears That Taste of the Sea exhibition

Intrinsically linked to The Garden of Africa was Tears That Taste of the Sea, a four-part installation exhibition that opened in spring 2021 at October Gallery. The four installations, each in different media, echo aspects of the cemetery in both their emotionally powerful forms as well as their evocations of loss and compassion.

Three large, black openwork sculptures, made of corten steel, were lit so that their sparse, fluid shapes could throw delicate shadows onto the white walls: This is a device familiar to Koraïchi, who has played on the transience of shadows to evoke the ephemeral character of life that contrasts with the permanence and rigidity of the steel medium.

Of these sculptural forms, which reference both calligraphy and bodies in motion, Koraïchi, now 74, explains that his background, too, is one that mixes traditions as well as media: “My work is rooted in the Islamic tradition, but I studied art in the Western mode, and I was trained in metalwork, pottery, sculpture and painting.” As a result, his range of media has, over decades, stretched further to textiles, including paintings on silk, canvas and paper, and to work in wood, bronze and steel. “When I was born, Algeria was a department of France. My country has been colonized by different peoples over thousands of years—Phoenicians, Romans, Syrians and then the French.” But going further back, he adds, there are rock paintings in caves in the Sahara region of Tassili n’Ajjer that date from 5,000 BCE and earlier whose iconography, vibrancy and delicacy enchanted him.

A spiritually charged, personal calligraphy

The second installation of the show comprised seven blue-and-white ceramic lachrymatory vases, or “tear gatherers.” Koraïchi says that it was at the Bardo Museum in Tunis that he first saw small, fragile vials of antique glass—precious and intimate repositories—made to store tears shed while mourning someone beloved, such as a relative. “I was inspired by people who had made such delicate, little glass containers, such as the ancient Phoenicians, also the Romans, the Greeks, the Iranians and later the Victorians in Britain, people in a multitude of places.” To him, it spoke of “a history of love.”

The tear gatherers he has made, however, are each half a meter tall. “To reflect the scale of death in the Mediterranean, the millions of uncollected tears, I made giant versions of the tiny bottles,” he says, “with four handles that could be held by both a mother and a father. The blue inscriptions on the surface of the vases symbolize the sea.”

“To reflect the scale of death in the Mediterranean, the millions of uncollected tears, I made giant versions of the tiny bottles, with four handles that could be held by both a mother and a father. The blue inscriptions on the surface of the vases symbolize the sea.”

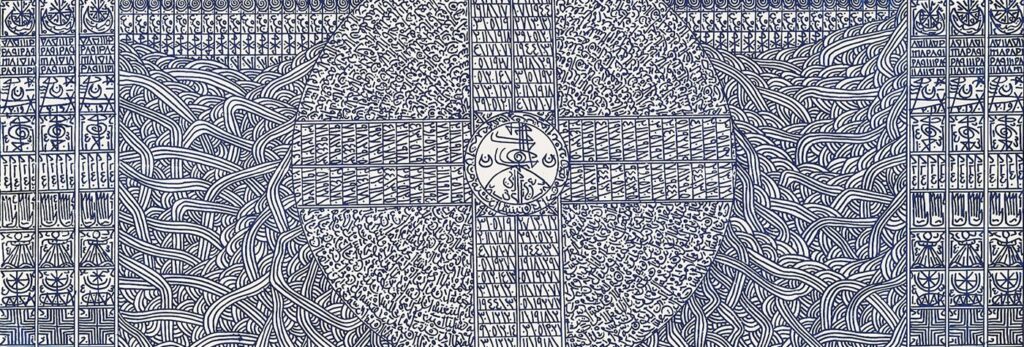

The third element of the exhibition was a large etching, 108.5 by 76 centimeters. Koraïchi titled it “The Garden of Africa”—like the cemetery—because the etching offers a similar story: “Symbolically, the rectangular figures enclose real-world elements, while the circle at the center, representing infinity, reveals elements from another realm. The isolated figure caught in the center of the circle stands at a crossroads, suggesting a traveler who arrives at that place of destiny where this Earthly journey ends and another voyage begins.”

In early 2020, when Koraïchi exhibited in Pakistan as part of Lahore Biennale 02, he taught an etching workshop to students at the National College of Art, and he arranged for all the required materials to be sent to Lahore. He selected The Garden of Africa as the workshop’s theme to emphasize how different countries can be linked by a contemporary crisis, especially since some of the migrants whose journeys ended so tragically near Zarzis may have set out from Pakistan. In addition to his large work, on which students collaborated with him, he mentored some 70 student prints.

Handkerchiefs of Hope

The fourth element of Tears That Taste of the Sea was a series of seven rectangular paintings on canvas, each on a rendition of a handkerchief, framed in black. “I was looking for something to accompany the lachrymatory vases that would extend the idea of a chronicle of intense emotions,” the artist explains. “Handkerchiefs imply softer, more pliant materials and implicate the powerful sense of smell. Today’s handkerchiefs have little value and are easily replaced by disposable tissues.” He indicates how in the past they were more symbolically significant, regarded for example among “love’s elaborate ruses,” which by absorbing traces of perfume, lipstick, perspiration as well as the salty residue of tears, they become palimpsests of intimate details in an individual’s life.

The painting series that followed is called Handkerchiefs of Hope, since as Koraïchi suggests, “If we could translate the encoded messages within them, we would discover signs of love and joy, as well as tears of loss, which are inseparably linked, since we shed most tears when we lose what we love the most.”

Born in 1947 in Ain Beida, Algeria, Koraïchi recalls that from a young age he was fascinated by the Arabic calligraphy he would find at home in old books whose pages were often illuminated with flourishes of arabesque. Beginning at age 3, before his regular day of school began, he attended a zaouia (a school for Qur’anic studies), where letters were an essential component of the curriculum. During an interview with October Gallery Director of Special Projects Gerard Houghton published in 2016, he explained: “Wherever my gaze fell was alive with the written word. My way of approaching the creative process mixes writing and drawing together, as in a gestural movement, like a visual musical score. For me, writing can only be sacred in origin. It is the visual sign that denotes divine activity.”

Venetia Porter, curator of the Department of Middle East and North Africa at the British Museum since 1986, describes Koraïchi’s work as “writing passion.” She included it in her 2008 exhibition, Word into Art: Artists of the Modern Middle East, which opened eyes and minds to the richness of calligraphic art. In Koraïchi’s particular, personal “alphabet,” letters become symbols and signs, and vice versa. Some are imaginary, like magical squares; others draw from forms used in Berber and Tuareg Tifinagh characters, as well as Chinese and Japanese ideograms. In effect, Koraïchi has developed a language of his own in which any medium, from black steel sculpture to gold-thread embroidery on silk, become his own spiritually charged calligraphy.

Koraïchi’s formal art education began in Algiers at the École des Beaux-Arts, and in 1971, aged 24, he moved to Paris. There he studied at several institutions including the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs, interacting with a cosmopolitan art world and developing his own approach to contemporary, international media.

While The Garden of Africa may be his most ambitious project to date, it is not unusual for his works to take years to finish: His homage to the 13th-century mystical poets Rumi and Ibn ‘Arabi, an installation titled Path of Roses, took from 1995 to 2005 to produce. In projects like this, he often combines materials and even at times collaborates with artisans in multiple places. For example, for his 2002 series Seven Variations of Indigo, he collaborated with Fadila Barrada, a Moroccan embroiderer, as well as expert Syrian linen artisans. The result was a series of silk-screened banners and squares on which inked wooden stamps—some antique and some carved by Koraïchi—were used to produce intricate patterns.

In 2011 Koraïchi’s selection of embroidered cloth banners from a series called The Invisible Masters won the internationally prestigious Jameel Prize for contemporary Islamic art. In his winning sequence, he used calligraphy, symbols and ciphers inspired by a range of scripts, languages and cultures to explore the lives and legacies of 14 great mystics of Islam. The Jameel Prize jury commended him for “how he had made his great spiritual and intellectual lineage accessible to all through the graphic language he had created out of his artistic heritage.”

October Gallery Director Chili Hawes adds her own accolade for Koraïchi’s “lifetime effort to convey, on the one hand, the historical developments of the broad world of Islam and, on the other, the expression of great beauty of the cycles of life from birth to death.”

With Tears That Taste of the Sea and The Garden of Africa, Koraïchi more than responds, more than inspires: He creates opportunities in which individuals, communities, organizations and governments can join him in cultivating a more empathetic future.

Source: AramcoWorld