Articles

Plague and poetry in the Middle East authors

Article theme: Arab, History, Literature.

Plague, pandemic and pestilence have long been themes for writers, historians and poets, from Giovanni Boccaccio’s medieval The Decameron and Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year to, more recently, Blindness by Nobel Prize winner Jose Saramago.

Nowhere is this more true than the Middle East and North Africa, which has a centuries-old tradition of writing about illness and medicine.

One of the most famous works is The Plague, by French-Algerian writer Albert Camus. Published in 1947, it is set in the Algerian city of Oran and based on the cholera epidemic which engulfed the city in 1849 (Camus chose to set his novel in the modern age). Many have also interpreted the story as about resistance to the Nazi occupation during World War Two.

That same year, Nazik al-Malaika broke poetry convention with her account of cholera in Cairo; one thousand years earlier, Ibn al-Wardi railed against the plague through an ode, only to succumb himself to the disease two days later.

But epidemic-related work from the region is not just fictional, going beyond the artistic and impressionist to also include hygiene guidance, travel books and hadiths (sayings, actions or silent approval attributed to the Prophet Muhammad and used as guidance for everyday life).

Works by the ninth-century writer Ibn Abi al-Dunya, as well as later works by Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani gave guidance on how to combat disease – much as we, in the 21st century, look to the World Health Organisation and other expert bodies for guidance.

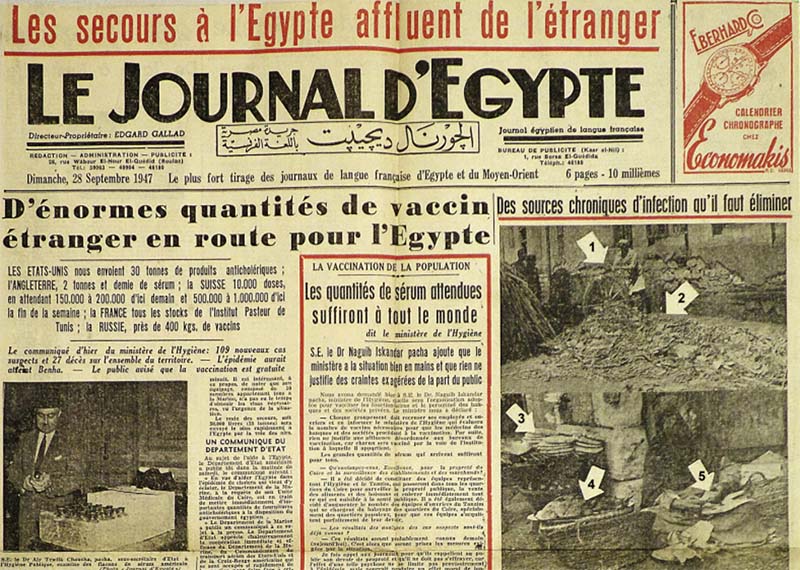

1947: Cholera in Egypt

Cholera, by the Iraqi poet Nazik al-Malaika (1923-2007), depicts the death, grief and agony that shattered Egypt during the last months of 1947.

The outbreak, which hit the country hard, is considered one of the largest incidents of the disease in Egypt during the 20th century, killing around 10,276 people out of a 20,805 recorded cases. During this period Egypt was cut off from the rest of the world, amid restrictions on travel, and the forceful isolation of patients and communities.

Although the origin of the infection was never proven, many Egyptians believed it was bought in by English soldiers returning from India (Egypt, which was a British colony earlier in the century, was still heavily garrisoned with UK troops during the late 1940s).

Al-Malaika conjures up vivid images of carriages carrying dead bodies and the silence that befell Egyptian streets; she also uses colloquial phrases for the illness such as “al-Shota” and “al-Heyda”, which translate as “swift” and “quick”.

Her style was hailed by critics at the time as ground-breaking in its use of free verse rather than the traditional Arabic ode, a form which is now almost 1,500 years old. As such, Cholera heralded a new chapter in Arabic poetry and inspired a new wave of Arab poets – called the Pioneer Generation – to experiment with different forms. During the 1990s, al-Malaika moved to Cairo, where she spent her last years.

It is dawn.

Listen to the footsteps of the passerby,

in the silence of the dawn.

Listen, look at the mourning processions,

ten, twenty, no… countless.

…

Everywhere lies a corpse, mourned

without a eulogy or a moment of silence.

…

Humanity protests against the crimes of death.

…

Cholera is the vengeance of death.

…

Even the gravedigger has succumbed,

the muezzin is dead,

and who will eulogize the dead?

…

O Egypt, my heart is torn by the ravages of death.

Translated by Husain Haddawy, with Nathalie Handal in Poetry of Arab Women: A Contemporary Anthology

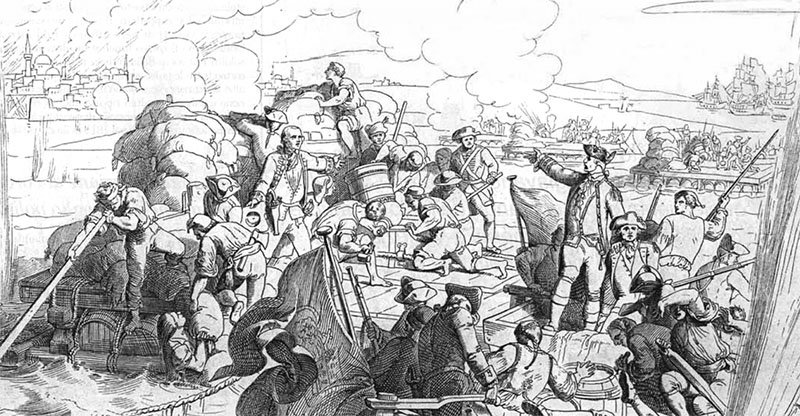

1784: Plague in North Africa

The popular depiction of pandemics has focused on outbreaks such as the medieval Black Death or the influenza outbreak 0f 1917-1920, which is wrongly labelled “Spanish Flu”. But epidemics can also be localised.

The volumes Ten Years’ Residence at the Court of Tripoli were penned by a “Miss Tully”, the sister-in-law of Richard Tully, the British consul in Tripoli, from 1784 onwards.

The port city, in modern-day Libya, was hit by the plague in 1785. Tully writes of how burning straw was used in homes as fumigation – along with what we would now recognise as social distancing:

“A friend is admitted only into a matted apartment, where he retires to the farther end of the room to a straw seat. No business is now transacted but with a blaze of straw kept burning between the person admitted into the house and the one he is speaking to.”

But the situation was just as severe in what is modern-day Tunisia. On 29 April 1785, Tully wrote:

The last few weeks several couriers have crossed the deserts from Tunis to this city, disseminating the plague in their way; and consequently the country round us is everywhere infected.

The plague reached the Tunisian city of Sfax in 1784 and was to kill an estimated 15,000 people, this in a port city of 30,000, double that of Tripoli.

Sfax had previously been hit by plague in 1622 and again in 1688, but the outbreak almost a century later was even more lethal, wiping out many of the ruling classes, including officials, politicians, the legal profession – and poets.

It began when sea merchants arrived after escaping the plague in Alexandria to the east. They were refused entry to Sfax but some sailors managed to breach the order.

Later, war was to follow plague. A Venetian merchant vessel was set alight by forces under the bey – or ruler – of Tunis, amid fears it had been infected with the plague. From autumn 1784 onwards and the following year, the Venetian fleet bombarded cities including Sfax.

1349: Pestilence in Syria

Ibn al-Wardi (1292-1349), a Syrian historian, was born in Maarat al-Numan. He wrote vividly about the Black Death, which swept through the world during the mid 14th-century, from Asia into the Middle East and then on to Europe.

Al-Wardi was living in Aleppo when the plague reached there in 1349, devastating the city for 15 years and claiming around 1,000 lives every day. His An Essay on the Report of the Pestilence, is a historical account of its impact on the Levante.

The plague began in the land of darkness. China was not preserved from it. The plague infected the Indians in India, the Sind, the Persians, and the Crimea. The plague destroyed mankind in Cairo. It stilled all movement in Alexandria.

Then, the plague turned to Upper Egypt. The plague attacked Gaza, trapped Sidon, and Beirut. Next, it directed its shooting arrows to Damascus. There the plague sat like a lion on a throne and swayed with power, killing daily one thousand or more and destroying the population.

Oh God, it is acting by Your command. Lift this from us. It happens where You wish; keep the plague from us.

Al-Wardi also wrote two poetry verses about the pandemic:

I do not scare from Black Death as others

It is but a martyrdom or victory

If I died, I rested from the rivalries

And If I lived, my eye and ear heald

He died two days later from the Black Death, which causes inflammation of glands on the neck, armpit and groin.

10th century: Fever in Egypt

Night Visitor, the ode by Iraqi-Syrian poet al-Mutannabi (915-965) to fever, is widely considered one the masterpieces of classical Arabic poetry.

Born in Kufa, Iraq, as Ahmed bin al-Hussein al-Kindi, al-Mutannabi’s nickname translates as “he who would be a prophet”. He treated poetry with zeal and relied on senses and experiences rather than mere abstractions for his inspiration.

Night Visitor depicts the condition as a shy lover, sneaking into Mutannabi’s bed after dark. The reader can viscerally feel and see this unwelcome guest, as the verse creates a sense of how fever makes its victim delirious, sweaty and fatigued.

Mutannabi’s metaphors and play on language poem were unique at the time, not least the idea of the fever – which is never medically specified – as a night visitor.

Mutannabi was under stress when he wrote the poem in Egypt, having just fallen out with best friend Sayf al-Dawla, the ruler of Aleppo, after intellectual in-fighting at the royal court. He was killed by bandits in 965 while travelling from Ahvaz in modern-day Iran. His influence at the time was such that news of his death reverberated like thunder around the Muslim world.

For she does not pay her visits save under cover of darkness,

I freely offered her my linen and my pillows,

But she refused them, and spent the night in my bones.

My skin is too contracted to contain both my breath and her,

So she relaxes it with all sorts of sickness.

When she leaves me, she washes me

As though we had retired apart for some forbidden action.

It is as though the morning drives her away,

And her lachrymal ducts are flooded in their four channels.

I watch for her time without desire,

Yet with the watchfulness of the eager lover.

Taken from Arabian Medicine: The FitzPatrick Lectures Delivered at the College of Physicians in November 1919 and November 1920.

9th century: Guidance in Iraq

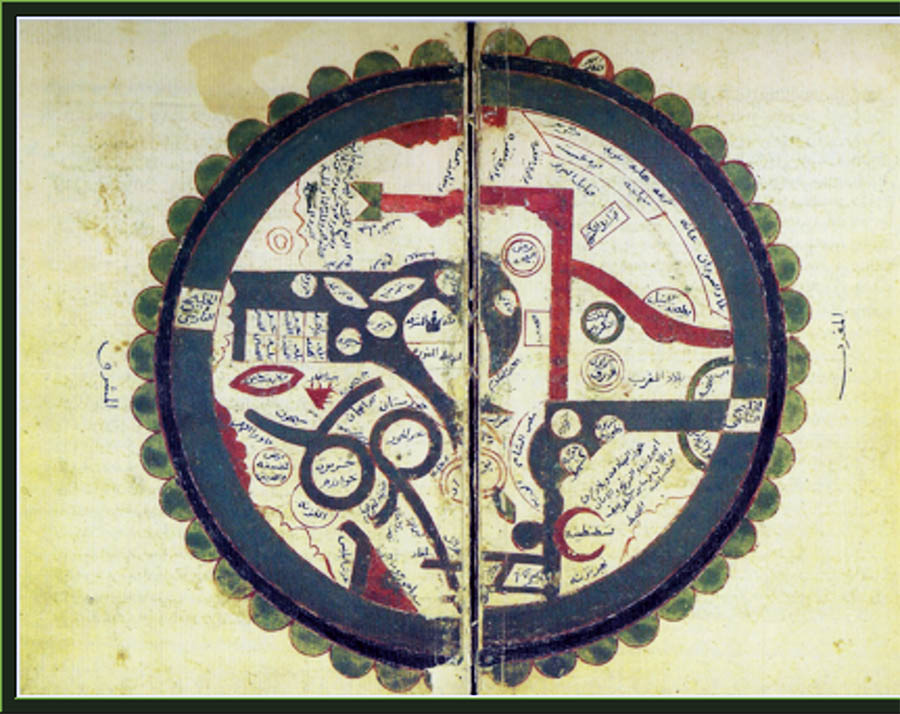

One of the earliest scholars to write a book about the Black Death was the Iraqi Ibn Abi al-Dunya (823-894). Revered as a teacher, he tutored the Abbasid caliphs, who ruled territory extending across North Africa, the Arabian peninsula, the Levant and modern-day Iran and Afghanistan.

During the early centuries of Islam, little was written about pestilence: until the ninth century, no serious scholar had dedicated a book to the subject or suggested measures to take to avoid contagion.

Ibn Abi al-Dunya was the first to change that: that he had access to the most powerful rulers of the time meant that his word carried weight (he was, in effect, the closest that Baghdad had to the WHO).

In The Book of Pestilences he included a hadith about fever:

The Messenger of Allah, peace and blessings be upon him, entered the home of Umm Sa’ib and he said, “What ails you, O Umm Sa’ib? You are shivering.”

She said: “It is a fever. Allah has not blessed it.”

The Prophet said: “Do not curse fever. Verily, it removes the sins of the children of Adam, just as a furnace removes dirt from iron.”

The Book of Illness and Atonements, meanwhile, gives examples of how people recovered from illness, including the Prophet Muhammad, during the early days of Islam.

His work was later cited by Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani (1372-1449), born in the Palestinian town of Askalan, who became a noted scholar in Cairo, one of the Middle East’s major seats of learning.

His book Offering Almsgiving in the Grace of Pestilence, was to prove one of the most popular works on the Black Death, which had just swept the eastern hemisphere.

Source: middleeasteye.net