Articles

Ivan Agueli, a painter against Islamophobia

Article author: Massimo Introvigne

Date of publication of the article: 03/06/2021

Year of publication: 2021

Article theme: Art, History, Islam, Islamophobia.

Review of the book Anarchist, Artist, Sufi: The Politics, Painting, and Esotericism of Ivan Aguéli, edited by Mark Sedgwick. Both the review and the book deepen on the many facets that characterized the political, religious and artistic work of Ivan Aguéli, as well as the fight he carried against Islamophobia.

Artist, anarchist, Theosophist, and Sufi, the Swedish artist coined the word in 1904, and defended Islam against Western stereotypes.

Artist, anarchist, Theosophist, and Sufi, the Swedish artist coined the word in 1904, and defended Islam against Western stereotypes.

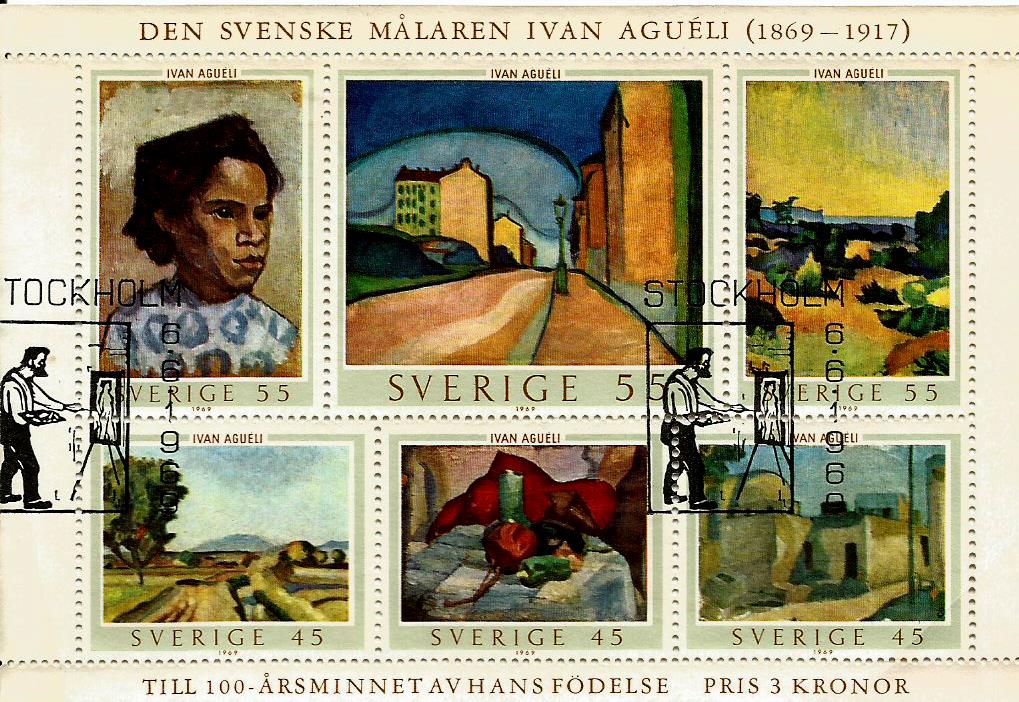

New religious movements significantly contributed, disproportionately with respect to the number of their members, to the birth and progress of modernist art. Among many artists who were Spiritualists, Theosophists, Rosicrucians, or followers of other spiritual movements—the list includes such luminaries as Piet Mondrian and Giacomo Balla, who were members of different branches of Theosophy—the Swedish painter Ivan Aguéli is a special case. He remained little known outside specialized circles for decades after his death in 1917, but has then been honored in Sweden by a museum in Sala, the town where he was born in 1869, and even stamps by the Swedish Postal Service.

Now Anarchist, Artist, Sufi: The Politics, Painting, and Esotericism of Ivan Aguéli (London: Bloomsbury, 2021), a collection of 14 essays and of some key texts by Aguéli, edited by Mark Sedgwick, one of the leading scholars of the esoteric current known as Traditionalism, offers the first comprehensive assessment in English of the Swedish painter and intellectual.

The many dimensions of Aguéli

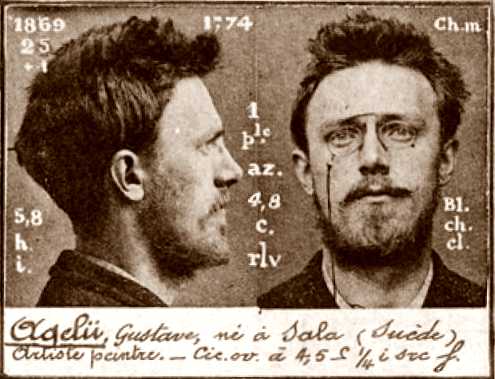

It is a magnificent book, introducing the reader to at least five different Aguélis—who are of course one and the same. First is Aguéli the anarchist, who was attracted to radical politics in France, where he originally went to study art, and met important anarchist leaders such as Peter Kropotkin, whom he visited in London. In 1894, Aguéli was suspected of complicity with anarchist terrorism and arrested in Paris, but his violence was purely verbal, and he was eventually found not guilty. Later, he was involved in illegal activities, including firing two shots in 1900 at a Spanish matador, missing him but wounding a banderillero, during his campaign against bullfights. This was part of a lifelong passion for animal rights, which developed after his meeting French feminist Marie Huot, 22 years his senior, with whom Aguéli developed a close friendship that may or may not have included a romantic element.

It is a magnificent book, introducing the reader to at least five different Aguélis—who are of course one and the same.

Later in life, Aguéli abandoned politics, but politics pursued him. During the unrest at the time of World War I in Spain, where he had been deported from Egypt in 1916 after having been falsely accused of being an Ottoman spy, he looked suspicious to different sides and was constantly harassed, which perhaps played a role in his death. He was mysteriously hit by a train near Barcelona on October 1, 1917.

The second Aguéli is the spiritual seeker, who became a member of different spiritual movements. As a young man, he became interested in the Swedish mystic Emanuel Swedenborg and was befriended by Adolph Boyesen, the first pastor of the newly established Swedenborgian Church in Stockholm. In Paris, he joined both Freemasonry and the Theosophical Society. As Per Faxneld notes in his chapter, these choices were not typical of “marginal” milieus, as both Theosophy and Freemasonry were quite mainline in Sweden at that time.

The third Aguéli is the Traditionalist. The role of the Swedish painter in the development of Traditionalism is controversial. Another book of 2021, Ivan Aguéli: The Pearl Upon the Crown, self-published by Oliver Fotros, explicitly accuses René Guénon, the French esoteric master at the origins of Traditionalism, of having hidden the key role of Aguéli in his introduction to Islam, and plagiarized works of his Swedish associate without quoting him. A chapter by Mark Sedgwick in Anarchist, Artist, Sufi clarifies what in fact Guénon owes to Aguéli, and how later Traditionalists tried to downplay the role of the Swedish artist. It was Aguéli who transmitted to Guénon a valid Sufi initiation. It was also through Aguéli that Guénon converted to Islam in 1911, although he started living as a pious Muslim only after he moved to Cairo in 1930. Without Aguéli, Sedgwick writes, perhaps “Traditionalism might have remained focused on Taoism and Vedanta, and Guénon might never have followed the path of Islam after 1930.”

The fourth Aguéli is the painter. The book clearly shows the influence of esotericism on his works, his relationships with other Theosophical painters and with books expounding esoteric theories of the colors. Even Sufism revealed itself in what Simon Sorgenfrei calls Aguéli’s “monotheistic landscapes.” On the other hand, Aguéli’s view of art was very much different from later Traditionalists, as he not only appreciated modernist movements such as Cubism (that Traditionalists regarded as anti-traditional and subversive) but even found in them a spiritual dimension.

A critic of Islamophobia

Readers of Bitter Winter would be mostly interested in the fifth Aguéli, the Islamic convert and critic of Islamophobia, but this dimension can only be understood in conversation with the other four. Aguéli spent significant periods of his life in Egypt. While he might have originally looked at the East with an orientalist gaze, and conceived his first trip as a quest for the exotic in the footstep of Gauguin’s move to Tahiti, in 1898 he converted to Islam and became for the rest of his life an apologist for his religion against Western critics. Whether he lived according to the precepts of Islam in his private life is a matter on which testimonies diverge.

Readers of Bitter Winter would be mostly interested in the fifth Aguéli, the Islamic convert and critic of Islamophobia, but this dimension can only be understood in conversation with the other four.

Aguéli privileged the mystical path of the Sufis, and was initiated into the Shadiliyya by Egyptian shaykh ‘Abd al-Rahman ‘Illaysh, who also introduced him to the works of the medieval mystic Ibn ‘Arabi and of the Algerian religious leader, and champion of the struggle against French colonialism, Abdelkader. Unlike other European converts, however, Aguéli, like Guénon, came to believe that in order to follow the esoteric Sufi path one should also embrace the exoteric life of a Muslim.

Some of Aguéli’s remarks in his defense of Islam against Christian missionaries and rationalist critics mentioned in the book edited by Sedgwick sounds quite naïve. For instance, he claimed that, while the Sufi ascetics he met were normally slim and emaciated, Catholic monks appeared as a well-fed and fat, raising doubts on their spirituality. Some authors of the book criticize his universalistic interpretation of Islam, which may be yet another disguised form of orientalism.

However, the book also calls the attention on the importance of Il Convito/Al-Nadi, a multilingual journal published in Cairo between 1904 and 1910, and created by Aguéli and Italian independent scholar of Islam and intelligence agent Enrico Insabato, whose story is told in the chapters by Paul-André Claudel and Alessandra Marchi.

It was in the article “The Enemies of Islam,” published in Il Convito/Al-Nadi in Italian in several installments in 1904, and reproduced in an English translation in the book, that Aguéli coined the Italian word “islamofobia” (Islamophobia), well before its first use in French in 1910 and in English in 1923. In this text, Aguéli distinguishes between different kinds of Islamophobia, one Christian, one racist, and one rationalist, and shows how they are all based on prejudices and stereotypes. The Swedish artist maintains, however, some stereotypes of his own, as he states that the bad reputation of Islam is sometimes due to Muslims being confused with “Levantines.” The latter, despised for their single-minded quest for “money and nothing else” through “all means,” are in fact according to Aguéli a population consisting mostly of Middle East Christians, “and rarely Jews,” although some Muslim Egyptians unfortunately also became similar to the “Levantines” in their misguided effort to become more “European.”

It was in the article “The Enemies of Islam,” published in Il Convito/Al-Nadi in Italian in several installments in 1904, and reproduced in an English translation in the book, that Aguéli coined the Italian word “islamofobia” (Islamophobia), well before its first use in French in 1910 and in English in 1923.

Yet, Aguéli’s role remains important as an early example of a Westerner identifying and denouncing Islamophobia. Today, it is sometimes argued that the word “Islamophobia” was coined by Arab or Turkish Muslims for their own geopolitical purposes. The book shows that this was not the case. If a political motivation was at work, it was the effort by the Italian government (for whose intelligence service Insabato worked) to portray Italy as a friend of Islam in opposition to other colonial powers, something that will remain a motif in Italian politics for several decades. “Islamophobia” was a word coined by Europeans to criticize other Europeans. Political motivations did play a role, but there is no reason to believe that Aguéli’s desire to defend Islam was not heartfelt and genuine.

Massimo Introvigne, Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR).

Source: Bitterwinter