Articles

Islamic carpets and fabrics in Renaissance art

Article author: Cristina de la Peña Pacheco

Date of publication of the article: 20/11/2023

Year of publication: 2023

Article theme: 2023, Art, Calligraphy, Europe.

There is a general awareness of the reason for the presence of textiles of Islamic origin in Renaissance European portraiture and religious painting, which affirms their introduction as a method of ostentation, capable of providing the figures depicted with social recognition in line with their economic capacity[1].

An indelible mark on Renaissance art

There are a large number of works in 16th-century Western art in which Islamic rugs or robes play an important role, usually as the principal decorative element, introduced in a highly visual manner and with a clearly evocative intention. Both northern and southern Europe make use of this resource; Nordic painters commonly place such carpets as tablecloths, while in places such as Spain and Italy they are more commonly found on the floor. So recurrent is their representation in the work of some renowned Renaissance artists that these carpets have come to be named, according to their style, in homage to each painter. Thus, there are catalogues of Holbein, Lotto, Bellini and Ghirlandaio carpets[2].

The presence of Islamic culture in the European world through Al-Andalus for almost 800 years left an important mark that should not be overlooked. The inheritance and survival of Islamic motifs is partly due to this, and is an important component in Renaissance art. On the other hand, the demand for Oriental carpets began to increase from the second half of the 15th century, as the Ottoman Empire grew, and Turkish carpets became the dominant product on the market in the 16th century, along with Mamluk and Persian carpets[3].

De Pictura as a starting point and Islamic geometry as an origin

The aim of this essay is to broaden the view of the representation of these textiles by considering other reasons that justify it, taking into account the scientific-artistic context in which Renaissance art developed and the generally overlooked connections between the Eastern and Western cultures of the 16th century. On the basis of a study of the humanistic awareness that governs the appearance of geometric perspective in the Renaissance and the theological bases in the geometric representations of Islamic art, arguments will be put forward in favour of an interpretation of this intercultural dialogue that manifests itself through art.

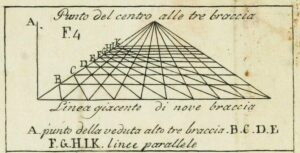

It was with the publication of Alberti’s De Pictura in 1435 that the foundations were laid in the European world for what would become the artistic basis of the Renaissance, based on the use of perspective, which acted as a synthesising element of humanist thought. This was built around a new axis, the human eye, as developed by the Genoese artist. In this way, and as Panofsky reflects in Perspective as Symbolic Form[4], an anthropocentric conception of art is generated which aspires as its maximum goal to the perfect representation of geometric perspective. To this end, a profound mathematical study is carried out which is favoured by the introduction of geometric resources into the works, allowing the construction of a mathematically unitary space.

Arabic calligraphy: another art form

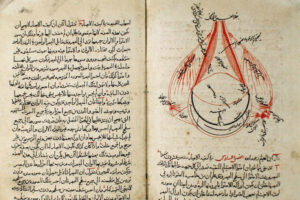

Titus Burckhardt says in The Art of Islam that “Arabic script is, by definition, the most Arabic of the fine arts of Islam”[5]. This may be assumed to be the reason why most of the carpets depicted in Renaissance art feature calligraphic decorations, generally in kufic script[6]: The Swiss historian’s work explores the importance of the geometric component in all Islamic artistic production, since it acts as a theological resource. However, by conditioning its formal representation in this way, it may suggest that European artists themselves take advantage of the symbolism of Islamic textiles and their social character to use them as a resource of perspective in painting, as they bring with them a marked geometric character rooted in the religious ideology of Islam. Burckhardt writes:

Calligraphers accept certain rules of proportion for each style. The unit of measurement is the “dot”, equivalent to the diacritical point under the final “ba'”. The letter with the greatest vertical extension is the “alif”, which consists of a certain number of dots. The maximum horizontal extension is determined by the lower half of a circle whose diameter is the length of the “alif”.

This demonstrates the rigorous mathematical study used by Muslims for the graphic representation of the word, which is due to the consideration of calligraphy as an artistic form since the writing of the Qur’an[7]. According to Hans Belting[8], these geometrical studies reached the treatise writers of the Renaissance through the 15th century Latin translation of Ibn al Haytham (Alhazen)’s 12th century work on optics, which was definitive for the development of three-dimensional representation on the two-dimensional plane[9].

For Titus Burckhardt, kufic calligraphy is arranged like a loom in which vertical and horizontal elements are interwoven to create a visually attractive network. This “calligraphic fabric” would act as a metapainting, or metatextile, within the Renaissance works in question, giving the painting its own geometric characteristics. By introducing into the plane of the pictorial support an element that claims to be three-dimensional (the textile work), which, in turn, contains two-dimensional elements arranged in a three-dimensional manner (the kufic/geometric characters), the representation of these carpets and fabrics becomes an important resource for the achievement of geometric perspective.

If we take, for example, the image of Saint Catherine painted by Fernando Yáñez de la Almedina, we can see how the painter adopts a clearly Renaissance aesthetic, inspired by the faces of Leonardo da Vinci and the decorum and proportional study typical of the Italians. However, the decoration of the saint’s clothing, covered with a series of kufic motifs taken directly from Islamic calligraphy, is striking from the outset. As this is a religious representation and not a private commission by a wealthy individual, the presence of such motifs is strange at a time when Muslims have been expelled from the Iberian Peninsula and trade relations through al-Andalus are non-existent. If the Prado Museum’s technical file on this work[10] is taken into consideration, it can be seen that little information is provided on the raison d’être of this textile representation.

The calligraphic motifs act in this work as a visual resource, giving the viewer a greater sense of realism, as the artist manages to integrate them fully into the mathematical composition. The letters move in and out of the plane, undulating over it thanks to their geometric character. The perspective achieved in this painting would therefore have been less visible had it not been for the introduction of the Arabic characters.

Yáñez de la Almedina repeated this exercise in the panel of the Visitation on one of the doors of the main altarpiece in Valencia Cathedral. Once again, the letters dance within the canvas itself which, if it were smooth, would not produce the three-dimensional effect provided by the calligraphic printing. Added to this is the lack of meaning of the inscription itself, which renders it devoid of semantic significance, making it a mere visual element[11].

A resource for achieving the Renaissance perspective

This idea is supported by the fact that, although the representation of Islamic textiles is present in 15th-century painting, it was not until the 16th century that they began to be introduced as three-dimensional objects that were not parallel to the plane of the support[12]. This leads us to think of the possibility of an intention on the part of Renaissance artists to integrate carpets and fabrics with geometric motifs from the Islamic imaginary as a visual resource, capable of manifesting their mastery in the use of perspective developed under the new humanist thought.

The same can be seen in Lorenzo Lotto’s work. The carpets that bear his name, decorated with geometric motifs adapted to the representation of perspective in the same way as Hans Holbein and his followers, are well known.

The Somerset House Conference, attributed to John de Critz, serves as a visual example for this theory. The oriental rug on the table around which the figures are arranged accentuates the vanishing point through the network of forms that make up its decoration. This element would act in the same way as the paved floors that have been present in Western painting since the dawn of perspective in the late medieval and modern world. Often, these marble floors act as the main visual attraction for the viewer, accentuating the depth of the scene and serving as a support for the painter. Once geometric perspective had been conquered, the role of structuring the pictorial space passed into the hands of the Islamic canvases. In Pedro Berruguete’s painting The Annunciation, from the late 15th century, the change of mentality in this sense can be seen in the covering of the floor with a carpet that allows the structuring of space through its geometric patterns, accentuating depth. Berruguete’s documented trip to Italy, which lasted until 1489, during which he studied perspective models, reveals the artist’s intention in introducing this element as a mathematical resource[13].

This supports the possible alternative interpretation of the presence of these textiles from the Islamic world in 16th-century European painting. Islamic religious art is mainly based on the idea of representing inanimate motifs treated through a geometrical filter as a theological resource. Thus, it has generated a whole religious visual ideology whose foundation is based on abstraction, as it contains a less contaminated idea of God, in a sense similar to that of the Neoplatonism of the medieval Christian world. This, together with the advanced science of the Islamic world, led to a profound study of geometric forms, which is manifested mainly in calligraphy, which is present in most of its textile products.

Cultural exchange beyond opulence

The important cultural exchange that took place between the Arabised world and the Christian world during the Middle Ages through the Iberian Peninsula, and the subsequent commercial exchange through the Ottoman Empire, is openly manifested in the artistic production of the West in the 16th century, mainly through the reproduction of Islamic carpets and fabrics in painting. This has often been interpreted simply as a method of ostentation and a display of the luxury and wealth possessed by those who have them. However, we must open our gaze in this sense, making a connection between the religious-mathematical foundation of the Islamic form and its introduction into the Renaissance artistic world, at a time when it seeks to develop geometric thought based on the new humanist mentality to the maximum.

Artists such as Yáñez de la Almedina, Lorenzo Lotto, Hans Holbein and Pedro Berrugete, known for their use of these objects in their pictorial production, serve as examples of painters who employ this resource as a tool for representing the visual and ideological innovations in art that originated in Italy from the work of Alberti.

Cover photograph: Lorenzo Lotto, The Alms of Saint Anthony (detail), 1542. Oil on canvas, Basilica of Saints John and Paul (Venice).

Notes

[1] A good study on this topic appears in: MILLS, J., Carpets in Paintings, Londres, National Gallery of Art, 1983; MILLS, J., Carpets in Pictures, The National Gallery, Londres, 1976; y MACK, R. E., Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300-1600, University of California Press, 2001.

[2] The Wikipedia page “Oriental carpets in Renaissance painting” [online] (Accessed 7 January 2021) provides a useful summary of this classification.

[3] DI CORTONA, E. G., “The representation of Turkish carpets in Venetian Renaissance paintings. Art and commercial relationship between this Italian sea republic and the Middle East” [online], Londres, SOAS University, p. 5 (Accessed 10 January 2021).

[4] PANOFSKY, E., La perspectiva como forma simbólica, Barcelona, Tusquets Editores, 2003.

[5] BURCKHARDT, T., El Arte del Islam: lenguaje y significado, Barcelona, Sophia Perennis, 2016, p. 57.

[6] This style of Arabic calligraphy, the most commonly used along with Nasji, is distinguished by its static character, as the letters are arranged on a vertical line that is not visible.

[7] ESSA, A., OTHMAN, A., Estudios sobre civilización islámica. La contribución de los musulmanes al Renacimiento (PÉREZ FERNÁNDEZ, A-R., trad.), Gutemberg, Malta, 2014. For more information about the importance of geometry in Islamic art, please see For more information about the importance of geometry in Islamic art, please see: NECIPOLGU, G., The Topkapi Scroll: Geometry and Ornament in Islamic Architecture, Santa Monica CA, Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities, 1995.

[8] Hans Belting discusses the relationship between Arabic mathematics and Renaissance art in BELTING, H., “Double Perspective: Arab Mathematics and Renaissance Art,” en Third Text Asia, 2, 2009; BELTING, H., Alhazen, Brunelleschi, and Western Philosophy, Munich, 2008 y BELTING, H., Florence & Baghdad. Renaissance Art and Arab Science, Cambridge MA, Harvard University Press, 2011, pp. 312.

[9] BIER, C., “Oriental Carpets, Spatial Dimension, and the Development of Linear P Linear Perspective: From Grid to Projective Grid”, en Textile Society of America, 9, Lincoln, Nebraska, 6 de octubre de 2010, p. 3.

[10] MUSEO NACIONAL DEL PRADO, Santa Catalina [online] (Accessed 10 January 2021).

[11] MORENO COLL, A., “Pervivencia de motivos islámicos en el Renacimiento: El lema «ʼIzz Li-Mawlānā Al-Sulṭān» en las puertas del retablo mayor de la catedral de Valencia”, en Espacio, tiempo y forma. Serie VII Historia del Arte, 6, 2018, p. 243.

[12] BIER, C., Idem, P. 6.

[13] BIER, C., Idem, p. 8.

Bibliography and webgraphy

“Alfombras orientales en la pintura renacentista”, Wikipedia [en línea] (fecha de consulta: 7 de enero de 2021).

BELTING, H., Alhazen, Brunelleschi, and Western Philosophy, Munich, 2008.

, “Double Perspective: Arab Mathematics and Renaissance Art,” en Third Text Asia, 2, 2009.

, Florence & Baghdad. Renaissance Art and Arab Science, Cambridge MA, Harvard University Press, 2011, pp. 312.

BIER, C., “Oriental Carpets, Spatial Dimension, and the Development of Linear P Linear Perspective: From Grid to Projective Grid”, en Textile Society of America, 9, Lincoln, Nebraska, 6 de octubre de 2010.

BURCKHARDT, T., El Arte del Islam: lenguaje y significado, Barcelona, Sophia Perennis, 2016.

DI CORTONA, E. G., “The representation of Turkish carpets in Venetian Renaissance paintings. Art and commercial relationship between this Italian sea republic and the Middle East” [en línea], Londres, SOAS University (fecha de consulta: 10 de enero de 2021).

ESSA, A., OTHMAN, A., Estudios sobre civilización islámica. La contribución de los musulmanes al Renacimiento (PÉREZ FERNÁNDEZ, A-R., trad.), Gutemberg, Malta, 2014.

MACK, R. E., Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300-1600, University of California Press, 2001.

MILLS, J., Carpets in Paintings, Londres, National Gallery of Art, 1983.

MORENO COLL, A., “Pervivencia de motivos islámicos en el Renacimiento: El lema «ʼIzz Li-Mawlānā Al-Sulṭān» en las puertas del retablo mayor de la catedral de Valencia”,en Espacio, tiempo y forma. Serie VII Historia del Arte, 6, 2018, pp. 237-258.

MUSEO NACIONAL DEL PRADO, Santa Catalina [en línea] (fecha de consulta: 10 de enero de 2021).

NECIPOLGU, G., The Topkapi Scroll: Geometry and Ornament in Islamic Architecture, Santa Monica CA, Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities, 1995.

PANOFSKY, E., La perspectiva como forma simbólica, Barcelona, Tusquets Editores, 2003.