Articles

Amazigh Identity in Morocco and Algeria

Article theme: Arab, Art, Craftwork, Ethnography, History, Human Rights, Landscape, Religions, Women.

The Amazighs are the oldest inhabitants of North Africa, a proof of that is their mention in the oldest hieroglyphs ever dicovered. These hieroglyphs are found in the temple of Amun at Thebes in Egypt. These autochtonous people, nevertheless, prefer to be called the Amazighs, the “free and noble men”, rather than the Berbers, a Greco-Roman appellation meaning “barbarians” which, in principle, designates any population outside of the axis romanus.

The Amazighs claim a physical presence in the Maghreb that is more than five thousand years old. Their community covers almost five million square kilometers, from the Egyptian-Libyan border to the Atlantic Ocean and from the Mediterranean coasts to Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso. Their culture, identity and civilization have long been despised and ignored by Arab governments of the region in the past, their rightful cultural claims have first being assimilated to the “colonial party”, then later interpreted as a blatant form of secessionism. But with the crisis of Arab ideologies during the Arab Spring and the beginning of the ebb of radical Islamism, these important factors favored the recognition of ethnic and cultural particularisms in North Africa and led to a renaissance of the Amazigh movement, especially in Morocco and Algeria.

Revival of Amazigh nationalism through culture and identity

In Algeria, the most determining event which made it possible for Amazigh culture to emerge is the Amazigh violent demonstrations of April 1980 in Kabylie that were caused by the prohibition of the conference of Mouloud Mammeri on the old Kabyle poetry. This ban was the trigger for the 1980 contestation movement which is known today as the Amazigh Spring (tafsut imazighen.) However, this historic movement has imposed Tamazight as a cultural landmark after many centuries of denial and rejection, throughout North Africa.

The Amazighs claim a physical presence in the Maghreb that is more than five thousand years old.

The Amazigh militants have fought since relentlessly, for full recognition of their culture, often risking their lives, against the dictatorship imposed by the Algerian regime upon independence of the country in 1962. The demand for identity, then, imposed itself as a benchmark for all the fightings that followed, be they for democracy, human rights, the fight against fundamentalism or all the struggles against oppression and regression of the present day.

For the Moroccan Amazighs, it all started about forty years ago with the creation of an associative network which demanded, as in Algeria, the recognition of Tamazight as an official language alongside Arabic. In 1994, after the end of the “lead years“, Hassan II dropped some ballast by launching televised news bulletins in different Moroccan Amazigh dialects. Nevertheless, it was until 2001 that Amazigh culture was officially recognized. Indeed, on that date the new sovereign, Mohammed VI, announced the creation of IRCAM, the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture in Morocco. He entrusted the management of this state organization to a recognized specialist on the issue, Mohammed Chafik, his former professor at the royal college.

But both in Algeria and Morocco, the recognition of the Amazigh civilization is merely cultural, not to say symbolic, in so much as most of the Amazigh areas are still poor and underdevelopped : lacking in schools, hospitals, roads, universities, factories, etc. The youth in these areas are jobless and the women illiterate and girls uneducated. From 1950 to 1900, the Amazigh population lived off remittances of workers in Europe but now because of economic problems there, they are not able to do that anymore and Morocco and Algeria have not been able or willing to adopt new models of developments in the Amazigh hinterland to fully develop these territories and empower their inhabitants.

Aspects of Amazigh identity

There are three major themes within the Amazigh culture, defined as the “trinity,” and easily recognizable in Moroccan and Algerian culture. The three themes have transcended Amazigh culture and have been accepted as the wider identity: The importance of language (Tamazight), the pervasiveness of the tribal democratic system and kinship system (ddm), and the strong connection to the land (tammurt).

The importance of language (Tamazight)

The most obvious theme in the Moroccan and Algerian communities of Amazigh nature is the importance of language within society. When one looks at the Amazigh people, there is a clear correlation between the relevance of language and the preservation of the culture throughout time.

Though the Arabs expressed themselves in more poetic and eloquent language, it is believed that they appreciated the way in which the Amazigh people used language as a uniting factor and a preservation element of their civilization.

The Amazigh people’s history and belief system was preserved in oral or written fashion whereby one generation would pass the history, wisdom, and laws to another. Despite having several distinct dialects of the language, the history and laws of the Amazigh people synced and survived countless invasions thanks to their native language.

When the Arab conquest occurred, the Arabs brought a similar appreciation for the essential nature of language and the role that the elderly should play in the preservation of culture. Even if one were to overlook the fact that both Arabic and Tamazight, the languages spoken by the Amazigh people, come from the Afro-Asiatic language family, both languages place a heavy emphasis on elders to ensure the continuation of the language, either through writing or oral recitation.

Though the Arabs expressed themselves in more poetic and eloquent language, it is believed that they appreciated the way in which the Amazigh people used language as a uniting factor and a preservation element of their civilization.

The idea of a nation-state was a foreign concept from the West that both the Amazighs and Arabs rejected in the Maghreb.

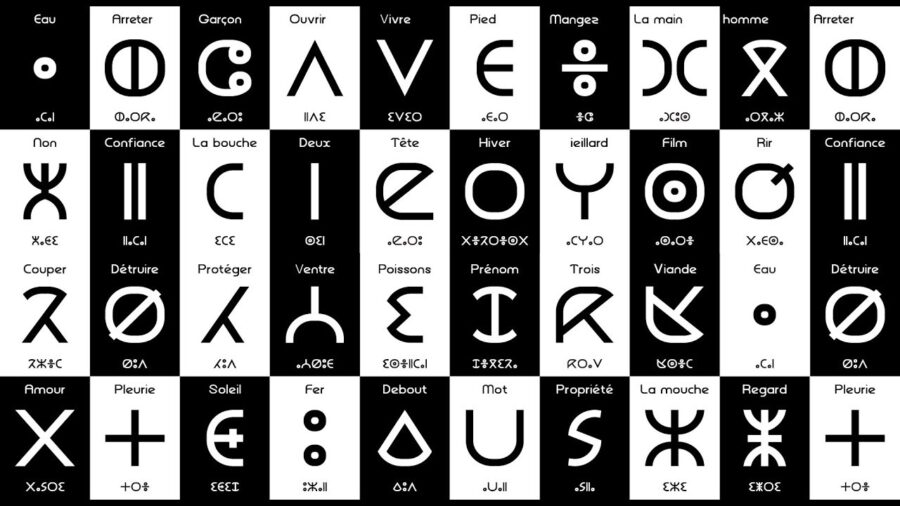

The relevance of language as a binding element became very apparent when the Algerain government inscribed in gold the official status of the Amazigh language in the constitution in 2016 and the King Mohammed VI amended the Moroccan constitution in 2011 to include Tamazight as a national language. A new written language was formed in neither Arabic or Latin script but an entirely new alphabet—Tifinagh— (ancient Amazigh script) to ensure the preservation of Amazigh history, traditions, laws, and wisdom.

This recognition provided the Amazigh an even greater acceptance into contemporary Algerian and Moroccan cultures. Despite the similarities, the move to recognize the language was more a political gesture than an inclusion of Tamazight into the society at large, which probably will take, in the end, more time.

Relevance of kinship

A second theme that one must look at when comparing Amazigh and contemporary Algerian and Moroccan cultures is the idea of kinship that spawns from the democratic tribal system.

The idea of a nation-state was a foreign concept from the West that both the Amazighs and Arabs rejected in the Maghreb. For both these ethnic groups, there is an acceptance that similarities between people are not defined by imaginary lines but rather that a given identity stems from a shared language, a shared history, and a shared religion.

This shared definition of identity resulted in a pervasive tribal system in both Amazigh and Maghrebi cultures. The tribal system is defined in terms of economically socialist but socially democratic system that can still be found in the world-famed hospitality of the North African peoples today.

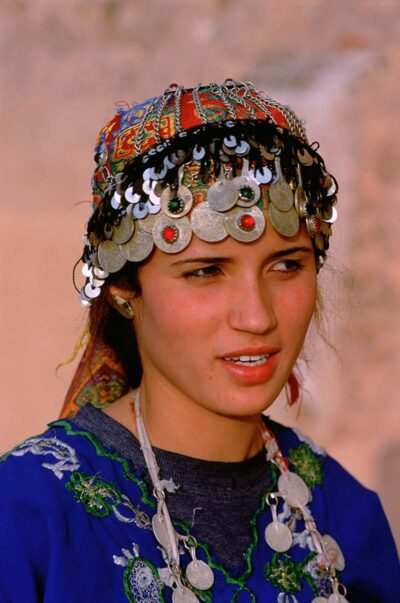

However, the idea of kinship that accepts people of different backgrounds is a relevant distinction between Amazigh and Arab culture. Even though the tribal system places an emphasis on the matriarch among the Amazighs, Arab culture prefers an influential and all-powerful patriarch. The relevance of this is that there continues to be a disenfranchisement of the Amazigh people in the laws and politics of Morocco and Algeria.

The centrality of the land

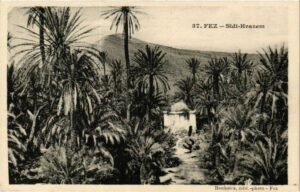

Finally, one must understand that the idea of a homeland resonates strongly with the Amazigh people. They have a unique relationship to the land that extends beyond the physical aspect and moves into the spiritual sphere.

The Amazigh viewed the land as a symbol that not only sustained life and beliefs but provided, also, protection from the imperialistic outside world.

The spiritual aspect of the land can be found in the  Moroccan and Algerian Islam (closely related to Sufism) today and that there is a strong relationship between the people in the city and the people in the mountains. This relates back to the idea that the Amazigh people accepted those who lived in the urban areas. The relevance of this relationship between urban and rural worlds emphasizes two distinct cultures in Morocco and Algeria that coexist and share similar linguistic and societal norms.

Moroccan and Algerian Islam (closely related to Sufism) today and that there is a strong relationship between the people in the city and the people in the mountains. This relates back to the idea that the Amazigh people accepted those who lived in the urban areas. The relevance of this relationship between urban and rural worlds emphasizes two distinct cultures in Morocco and Algeria that coexist and share similar linguistic and societal norms.

To conclude

The history of the Amazighs of North Africa is very vast and very rich. Their culture in its Mediterranean, African, Eastern, European or international influences, is particularly distinguished by :

– an unfailing link to the land tamurt/akal ;

– with a strong sense of the sacredness of the language Tamazigh/awal ;

– of great conviviality and sharing twiza ; and

– a great sense of community ddm/tghaghart.

The idea of an Amazigh nation is built on the model of previous national movements around a people, the Imazighen, a language Tamazight, and a territory, Tamazgha/North Africa. This mythical original link between the people and the land makes them an “indigenous” people in the sense defined by the United Nations as :

“social groups with a social and cultural identity different from that of the dominant society, which makes them likely to be disadvantaged in the development process.“

The Amazigh of Morocco and Algeria have a complex relationship with language, societal norms, and the land. However, if one were to remove any one of these Amazigh cultural aspects, it is fairly likely Morocco and Algeria would have a different set of beliefs and way of life, for sure.

* Dr. Mohamed Chtatou is a Professor of “Business Communication” at Université Internationale de Rabat -UIR- and of “Education” at Université Mohammed V in Rabat, as well. Besides, he is currently a political analyst with Moroccan, American, Gulf, French, Italian and British media on politics and culture in the Middle East, Islamism and religious terrorism. He is, also, a specialist on political Islam in the MENA region with interest in the roots of terrorism and religious extremism.

Annotated bibliography :

- Abun-Nasr, Jamil M., ed. A History of the Maghrib in the Islamic Period. Cambridge, UK : Cambridge University Press, 1987.

- Excellent resource for students and scholars interested in the history of the Amazighs in particular and the history of the maghrib (North Africa) in general from the Islamic conquest in the 7th century to the late 20th century.

- Bousquet, G. H. Les Berbères : Histoires et institutions. Paris : Presses Universitaires de France, 1957.

- A classic general historical and sociological study of Amazigh groups, languages, and institutions. Original publication in French.

- Brett, Michael, and Elizabeth Fentress. The Berbers. Malden, MA : Blackwell, 1996.

- This is a well-written and well-illustrated general history of the Amazighs by two experts on the subject. The book is a valuable resource for students and scholars, as it also provides a rich bibliography on all aspects of Amazigh history, culture, and institutions.

- Camps, Gabriel. Des rives de la Mediterranèe aux marges meridionales du Sahara : Les Berbères. Paris : Edisud, 1996.

- A brief history of Amazigh kingdoms and the transformation of Amazigh societies into what is now known as Arab maghrib, written by an authority on the subject of Amazigh history and culture. Original publication in French.

- Ibn Khaldun, Abd al-Rahman. Histoire des Berbères et des dynasties Musulmanes de l’Afrique septentrionale. 4 vols. Translated from Arabic by Le Baron de Slane. Paris : Librarie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 1925.

- A seminal work on the origins of the Amazighs, their social structure, and their political systems produced by the 14th-century historian and sociologist Ibn Khaldun, who gained the title of “the historian of the Amazighs.” Original publication in French.

- Lacoste, Camille, and Yves Lacoste, eds. Maghreb : Peuples et civilisations. Paris : La Decouverte, 2004.

- A valuable and varied collection of articles about the peoples of North Africa and their religion, culture, language, and civilizations written by experts in various fields of knowledge and research and various backgrounds : sociologists, anthropologists, ethnologists, and historians. Original publication in French.

- Maddy-Weitzman, Bruce. The Berber Identity Movement and the Challenge to North African States. Austin : University of Texas Press, 2011.

- A rich historical analysis of the origins of Amazigh identity, the domination of Amazighs by successive colonial rules, and the current struggles of Amazigh movements for recognition by North African states.

- Shafiq, Muhammad. Lamḥah an thalathah wa-thalathina qarnan min tarikh al-Amazighiyin. Rabat, Morocco : Dar al-Kalam, 1989.

- This book is a brief history of the Amazighs that spans over thirty-three centuries. The author discusses the origins of the Amazigh and their linguistic and cultural characteristics over centuries of foreign domination and influence. Original publication in Arabic.