Articles

Al-Andalus’ Naturalists and the Mediterranean

Article author: Mariam Gracia-Mechbal (La Reina de los Mares)

Date of publication of the article: 24/10/2019

Year of publication: 2019

Article theme: Al-Andalus, History, Nature.

The orientalization of the science of Al-Andalus was essential for the later development of the knowledge and thought of both the Iberian Peninsula and the rest of Europe during the Middle Age. Many travelers moving towards the East returned to Al-Andalus carrying a wide number of treatises of Greek-Byzantine origin, Hindu, and Persian… translated into Arabic. And, obviously, over time, they were reviewed, studied, commented, and extended, so that Al-Andalus became the source of knowledge that would feed Europe for the next centuries.

The orientalization of the science of Al-Andalus was essential for the later development of the knowledge and thought of both the Iberian Peninsula and the rest of Europe during the Middle Age. Many travelers moving towards the East returned to Al-Andalus carrying a wide number of treatises of Greek-Byzantine origin, Hindu, and Persian… translated into Arabic. And, obviously, over time, they were reviewed, studied, commented, and extended, so that Al-Andalus became the source of knowledge that would feed Europe for the next centuries.

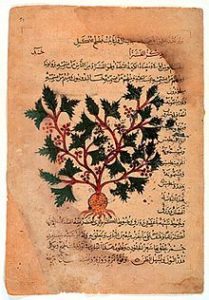

In the field of Natural science, this change can be observed in the 10th century, through the arrival of the Medical Material of Dioscórides to the Andalusi capital. This ancient pharmacological encyclopedia was sent by the emperor of Byzantium, Constantino VII Porfirogéneta, to ʽAbd al-Raḥmān III, as a gesture of goodwill to the Caliphate court. From that moment onwards, we witness a great dedication to botany. In particular, big developments were made in the classification and morphological description of botanical species, and their medical and pharmaceutical uses.

Many travelers moving towards the East returned to Al-Andalus carrying a wide number of treatises of Greek-Byzantine origin, Hindu, and Persian… translated into Arabic. And, obviously, over time, they were reviewed, studied, commented, and extended, so that Al-Andalus became the source of knowledge that would feed Europe for the next centuries.

This interest encouraged doctors, agronomists, and botanists to experiment and apply the knowledge they had acquired through those books, so that the cataloguing of plant life became the main goal of naturalists. With this purpose, they didn’t hesitate in traveling across the Iberian Peninsula, the Maghreb, and Mashreq, through the Southern shore of the Mediterranean, in order to know, first-hand, the different botanic species living there, their names, and the pharmaceutical, and traditional uses these regional plants received.

As a result of this knowledge, we see the emergence of independent botanical treatises, as well as the development of vegetable pharmacopeia, which reached levels never seen before.

Essential works

Of all the texts written during the Al-Andalus period, it is interesting to highlight what many of us consider the most important and valuable botanical encyclopedia written during the Middle Age, the Kitāb ʽUmdat al-ṭabīb fī maʽrifat al-nabāt li-kull labīb, by Seville’s doctor, agronomist and botanist Abū l-Jayr al-Išbīlī.

The information gathered by this treaty is rich and diverse, in addition to the many testimonies of the author’s experiences. His notes allow us to know the regions where Abū l-Jayr studied, as it points out at many places, the plants he observed, where he planted, the uses he gave them, etc.

The information gathered by this treaty is rich and diverse, in addition to the many testimonies of the author’s experiences. His notes allow us to know the regions where Abū l-Jayr studied, as it points out at many places, the plants he observed, where he planted, the uses he gave them, etc.

In addition to this, many are the sources it cites. Among them, two classics stand out, Discórides and Galeno. They are followed by a large number of classic, Eastern, Northafrican, and Andalusi authors specialized in medicine, botany, pharmacology, lexicography, linguistics, etc. Along with this sources, he relies on the opinion of naturalists, herbalists, and anonymous traders who provide him with direct, oral information, especially in those species he couldn’t see personally. Thus, he provides information about places such as Ceuta, Morocco, Egypt, Syria-Lebanon, Tunisia, Sicily, etc.

For all this, it is a predominantly practical work of great interest for the study of ethnobotanics, as well for other fields. In addition to the information it provides on botany, pharmacology, and medicine, the text offers information on name places, linguistics, folklore, etc.

Likewise, looking at the Mediterranean region, it is interesting to note another work whose original manuscript hasn’t been preserved, although we know about it thanks to the many times it is cited in the Kitāb al-Ŷāmiʽ li-mufradāt al-adwiya wa-l-agḏiya, from the famous botanist from Malaga, Ibn al-Bayṭār. We are talking about the Riḥla mašriqīya of Abū l-ʽAbbās al-Nabātī, who, in 1217 undertook a three-year journey to the towards the East with a double purpose: religious, as part of the pilgrimage to Mecca, and scientific.

In al-Nabātī’s treaty, he describes the plants he had come to know in Morocco, Tunisia, Tripoli, Egypt, Syria, Iraq, the Hejaz, the Red Sea, and Sicily, providing much new information based on his own observations and experiences. These citations are more descriptive than scientific, and approximately half of them refer to plants unknown or barely known in Al-Andalus, which gives it a great value.

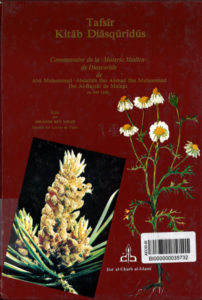

Before leaving for the East, this author spent many years studying in Al-Andalus and the current Morocco. From that period, we find the Šarḥ likitāb diyāsqūrīdūs fīha yūlà al-ṭibb, that makes many references to Maghrebi species. It provides many details of the places where his mentor, ʻAbd Allāh b. Ṣāliḥ, studied along with the Berbers, providing many names of plants in Romance language, as well as on the different Berber dialects from Morocco and Algeria.

Before leaving for the East, this author spent many years studying in Al-Andalus and the current Morocco. From that period, we find the Šarḥ likitāb diyāsqūrīdūs fīha yūlà al-ṭibb, that makes many references to Maghrebi species. It provides many details of the places where his mentor, ʻAbd Allāh b. Ṣāliḥ, studied along with the Berbers, providing many names of plants in Romance language, as well as on the different Berber dialects from Morocco and Algeria.

This fact grants this work a great importance from a linguistic perspective, as it wasn’t frequent in these works to find Berber terminology, thus, making clear its contribution to botanist terminology and the history of Berber language. It also refers to other places such as Tangiers, Valencia, Gibraltar, Melilla, etc. Lastly, as we are talking of a work based on his own experience, he makes a great distinction between those plants he has seen personally and those he hasn’t.

In this brief contribution, we have tried to outline the importance of the trips carried out by Al-Andalus’ naturalists across the Mediterranean for the production of knowledge and the development of new scientific areas of study during the Middle Age. The data these travelers gathered exceed the field of natural sciences, providing interesting information on the uses and practices of the many places they visited, both to learn or to put into practice their recently acquired knowledge.

Source: La Reina de los Mares

Translation: Alfonso Casani – FUNCI

Bibliography

ABŪ L-JAYR AL-IŠBĪLĪ, Kitābu ʻUmdati ṭṭabīb fī maʻrifati nnabāt likulli labīb, eds. y trads. J. Bustamante, F. Corriente, y M. Tilmatine. 4 vols. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas, 2004-2010.

― Kitāb ʻUmdat al-ṭabīb fī maʻrifat al-nabāt, manuscrito n.º XL de la Colección Gayangos, Real Academia de la Historia de Madrid.

― Kitāb ʻUmdat al-ṭabīb fī maʻrifat al-nabāt li-kul labīb, Manuscrito 3505, Biblioteca General de Rabat.

IBN AL-BAYṬĀR, Al-Ŷāmiʻ li-mufradāt li-adwiya wa-l-agḏiya, 4 t., 2 vols. Būlāq: Dār al-Madīna, 1291 H. (reimp. facsímil).

― Al-Ŷāmiʻ al-mufradāt li-adwiya wa-l-agḏiya. 2 vols. Bayrūt: Dār al-kutub alʻilmiya, 1992.

― Tafsīr kitāb Diyāsqūrīdūs, ed. I. ben Mrad. Beirut: s.n., 1989. (4-30043)

― Traites des simples, trad. L. Leclerc. Paris: Institute du Monde Arabe, 1987.

SAMSO, Julio. Las ciencias de los antiguos en al-Andalus. Madrid: Mapfre, 1992

VERNET, Juan. La ciencia en al-Andalus. Sevilla: Editoriales Andaluzas Unidas, 1986