Articles

Interfaith dialogue through travel literature

Article author: Dr Mohamed Chtatou

Date of publication of the article: 13/07/2021

Year of publication: 2021

Article theme: History, Literature, Religions.

Dr. Mohamed Chtatou

The rihla or travel literature has played an outstanding role in the registration of the habits and traditions of the different peoples around the globe and contributing to connecting the different regions and communities. In doing so, it has promoted the preservation of the visited regions’ historical features, many of whom would have remained unknown it was not for this literature, and it has contributed to the creation of an interfaith dialogue, directly influencing other regions and societies. In a first article published on FUNCI, we focused on the beginnings of the Rihla (12th to 14th centuries) and the main authors responsible for its development. This second delivery delves on the later development of the rihla, in the 18th and 19th centuries, by focusing on several Easter and Western authors and their role in the promotion of intercultural dialogue.

If we are to believe the major myths and tales, travel is part of the human adventure. Whether man embarks for good or toward a promised land (Abraham or Moses), experiences numerous tribulations before returning to his point of origin (Ulysses), takes to the road to seek wisdom through multiple encounters (Buddha) or goes off to discover terra incognita (Christopher Columbus or Marco Polo), he enriches his perception of the world. In an era when travel is part of our daily life.

Maybe one of the best illustrations of applied intercultural dialogue is travel literature, for over centuries people have moved from one geographical location to another for work, education, trade, diplomacy, leisure and have come in interaction with other people of different color, culture or creed. These interactions occur in different ways, they can be violent and disruptive or peaceful and amicable, and obviously when we talk about violence we do not mean occupation or conquest but merely erroneous cultural approach resulting from lack of communication due to preconceived ideas. The truth of the matter is that humans build far too many walls around them and too few bridges to meet. Is it fear? Is it superiority? Is it hatred? Or is it all these things put together? Actually there is no ready-made answer but a multitude of scenarios…

The Rihla as a link between the East and the West

The letters of Lady Mary Montagu in the 18th century

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689–1762), by birth Lady Mary Pierrepoint, was the eldest daughter of Evelyn earl of Kingston (afterwards marquis of Dorchester, finally duke of Kingston), and was born at her father’s seat of Thoresby in Nottinghamshire, in the year 1690. Displaying great attractions as well as sprightliness of mind since her early years, she was her father’s favorite and pride, who, having lost his wife in 1694, introduced his daughter to society, and made her preside at his table, almost before she had well outgrown her childhood.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689–1762), by birth Lady Mary Pierrepoint, was the eldest daughter of Evelyn earl of Kingston (afterwards marquis of Dorchester, finally duke of Kingston), and was born at her father’s seat of Thoresby in Nottinghamshire, in the year 1690. Displaying great attractions as well as sprightliness of mind since her early years, she was her father’s favorite and pride, who, having lost his wife in 1694, introduced his daughter to society, and made her preside at his table, almost before she had well outgrown her childhood.

In August 1712, without the consent of her father, Lady Mary married Edward Wortley Montagu, Esq., eldest son of the Hon. Sydney Montagu, and grandson of the first earl of Sandwich. Her letters to Mr. Montagu before their marriage, which have been published entirely for the first time in the late complete edition of her works by her great grand-son, the present Lord Wharncliffe, prove that she had already attained much of that sharpness both of style and thought for which her writings are known, as well as a maturity of judgment far beyond her years.

Between 1716 and 1718, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu accompanied her husband during his appointment as ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, travelling overland through Vienna, Belgrade and Adrianople, staying in Constantinople, and returning via Tunis, Genoa and Paris. The Turkish Embassy Letters is a selection of the letters she wrote during that period. She worked on it during her lifetime, but it was not published until after her death in 1762.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu was described by a contemporary as “one of the most extraordinary shining characters in the world.” Her letters tell of her travels through Europe to Turkey in 1716, where her husband had been appointed Ambassador. Her liveliness makes them delightfully readable, and her singular intelligence provides us with insights that were exceptional for her time. Her ability to study another culture according to its own values, and to see herself through the eyes of others, makes Lady Mary one of the most fascinating and accomplished early travel writers.

As the balance of power shifted from the Ottoman Empire to Europe following the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, despite the similarities in the subordinate positions of women in the East and West, the veiled woman became one of the most powerful symbols of the “irrationality” of Islam. The burgeoning industry of 18th and 19th century travel literature, which satisfied the desire for tales of the “exotic” East, reveled in stories of the oppressed veiled woman. These often “imaginary” accounts (men had no access to women’s quarters) of the women of the Orient found expression in such works as Aaron Hill’s A Full and Just Account of the Present State of the Ottoman Empire, Jean Dumont’s A New Voyage to the Levant, John Covel’s Early Travels in the Levant, and Robert Heywood’s A Journey to the Levant. At once voyeuristic and indignant, these travel narratives distracted attention from the gender inequities at home, presenting the Orient as a place in need of rescue and reinforcing the idea of Europe as free, fair and civilized, supporting the role of the Empire. These narratives also allowed the male reader to vicariously experience the role of hero while satisfying his fantasies of penetration and domination.

However, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, one of the first female travelers in the Ottoman Empire, challenged these voyeuristic tales about Turkish women and their enslavement by insisting on the liberty of veiled women. In her Turkish Embassy Letters, she disrupts the pervasive orientalist discourse and the East/West divide by throwing into confusion the rhetoric of Western modernity and reason and Eastern barbarism and irrationality, at least as it is secured by the figure of the (un)veiled woman. In this description, Montagu invokes the tradition of eighteenth-century travel narratives that delight in imaginative descriptions of the abuse and enslavement of the oriental woman and “lament on the miserable confinement of the Turkish ladies” (134) but then shifts the gaze to her own imprisoned body. Teasingly opening her shirt and inviting rescue, she forces attention on the English social order and complicates the role of the heroic colonialist reader. This undressing or unveiling does not naively assume an unfettered freedom but rather displays a gendered social order that underlies the very rhetoric of reason.

Montagu’s writing about Turkey counters the prevalent orientalist assumptions in the travel accounts of her day, which support empire building, and opens a space where colonialist impulses are subject to critique.

On this distinguished lady traveler and Augustan age intellectual, Carolyn McDowall, writes inThe Culture Concept Circle, in 2016 an article entitled “Lady Mary Wortley Montagu – Adventuress & Woman Of Influence”:[i]

“The Turkish Embassy Letters of the Right Honourable Lady Mary Wortley Montague, written during her travels in Europe, Asia and Africa to persons of distinction, appeared in 1763, published the year following her death.

She had charged the Rev. Benjamin Sowden in 1761 when she was heading back to London following her husband’s death, to do with them whatever he decided and today they are the basis for her literary reputation.

Lady Mary had commented when reading the letters of Marie de Rabutin-Chantal, Marquise de Sévigné and asserted that ‘… without the least vanity, mine will be full as entertaining 40 years hence’.

They were a best seller and became a model for lively letter writing, inspiring and influencing sensibilities about what constituted an effective and entertaining personal letter.

Her description of life inside a harem would go on to influence the work of Orientalist painters, illustrators, and writers in the nineteenth century.

Would have loved to have read her diaries but her daughter burned them after she had died of cancer seven months after arriving home.

The Complete Letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, 3 vol. (ed. Robert Halsband, published 1965–67) was the first full edition of Lady Mary’s letters published.”

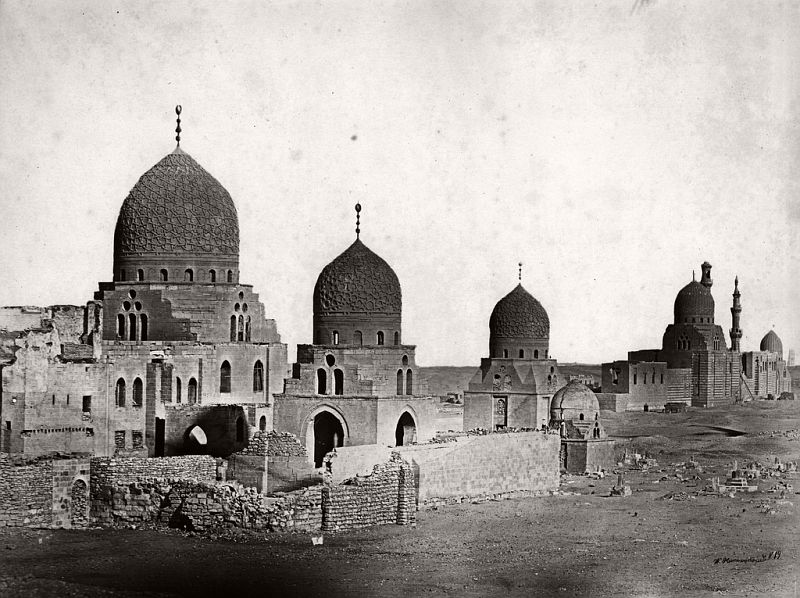

19th Century travel literature: the exchange between Europe and Egypt

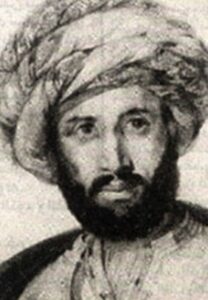

Rifa’a al-Tahtawi (1801-1873)

Rifa’a al-Tahtawi was born in the village of Tahta, Sohag, the same year the French troops evacuated Egypt. He was an Azharite, recommended by his teacher and mentor Hassan El-Attar to be the chaplain of a group of students Mohammed Ali was sending to Paris in 1826. Many student missions from Egypt went to Europe in the early 19th century to study arts and sciences at European universities and acquire technical skills such as printing, shipbuilding and modern military techniques. According to his memoir Rihla (Journey to Paris), Tahtawi studied ethics, social and political philosophy, and mathematics and geometry. He read works by Condillac, Voltaire, Rousseau, Montesquieu and Bezout among others during his sojourn in France.

Rifa’a al-Tahtawi was born in the village of Tahta, Sohag, the same year the French troops evacuated Egypt. He was an Azharite, recommended by his teacher and mentor Hassan El-Attar to be the chaplain of a group of students Mohammed Ali was sending to Paris in 1826. Many student missions from Egypt went to Europe in the early 19th century to study arts and sciences at European universities and acquire technical skills such as printing, shipbuilding and modern military techniques. According to his memoir Rihla (Journey to Paris), Tahtawi studied ethics, social and political philosophy, and mathematics and geometry. He read works by Condillac, Voltaire, Rousseau, Montesquieu and Bezout among others during his sojourn in France.

He was an Egyptian religious scholar trained in Islamic disciplines at al-Azhar by a shaykh sympathetic to the reform program of Muhammad Ali. After his return, he helped develop a new educational system in Egypt and encouraged language instruction and translations. He worked to develop an intellectual framework for the integration of European and Islamic ideas, laying the foundation for Islamic modernist thought, and also laid the foundation for Egyptian nationalism.

Rifa’a al-Tahtawi was a writer, teacher, translator, Egyptologist and renaissance intellectual. Tahtawi was among the first Egyptian scholars to write about Western cultures, in an attempt to bring about reconciliation and an understanding between Islamic and Christian civilizations. He founded the School of Languages in 1835 and was influential in the development of science, law, literature and Egyptology in 19th-century Egypt. His work influenced that of many later scholars including Muhammad Abduh.

On this enlightened Egyptian traveler of the 19th century, Barbara Winckler writes in Qantara an article entitled “France as a Role Model” on his travel experience in France:[ii]

“His book, with the virtually untranslatable title Takhlis al-ibriz fi talkhis Baris (The Refinement of the Gold in a Comprehensive Depiction of Paris), couched in the rhyming prose typical of the time, appeared in 1834. Ein Muslim entdeckt Europa (A Muslim Discovers Europe), as the title of the German translation has it, describes Tahtawi’s impressions of Paris, where he lived from 1826 to 1831 as the imam of the first study mission sent by Muhammad Ali.

At the time Egypt was going through a period of transition. Napoleon’s Egyptian expedition of 1798 and the following three years of occupation confronted Egypt with Europe’s glaring superiority, above all in the military and technological spheres; it became imperative to catch up. According to the strategy, those who had studied in Paris could replace the French experts who had been imported for the purpose.

In addition, the largely secularized France was regarded as less “risky” for Muslims. After centuries of disinterest in a supposedly backwards Europe, Tahtawi’s book was the first modern Arabic description of a European country. Written in an objective tone, it was meant to function as a practical travel guide, educating, uplifting and encouraging imitation.”

And goes on to talk about his fascination with the French culture and civilization and an idealized view of the French educational system:

“Much taken by French learning, the educational system and scientific achievements, Tahtawi often conveys an idealized picture in which “all the French” can read and write, own a library, and are passionate scholars. The republican political system is described positively, but the author also comments that Islam provides good arrangements as well.

Tahtawi, born in Upper Egyptian Tahta as the scion of a prominent family, was one of the pioneers of the nahda, the Arab Renaissance. His studies at Cairo’s Azhar University, with its traditionally religious curriculum would hardly have seemed to predestine him for this role, though he did study geography, history, astronomy and the natural sciences even at that time.

Doubtless crucial for the further course of Tahtawi’s development was his participation in the study mission, which, as for the other participants, laid the foundation for a subsequent career in the army or the administration.

It also proved fortunate that Tahtawi – unlike the other participants – was not delegated to a technical specialization and could instead devote himself to translating and reading a broad range of literature.”

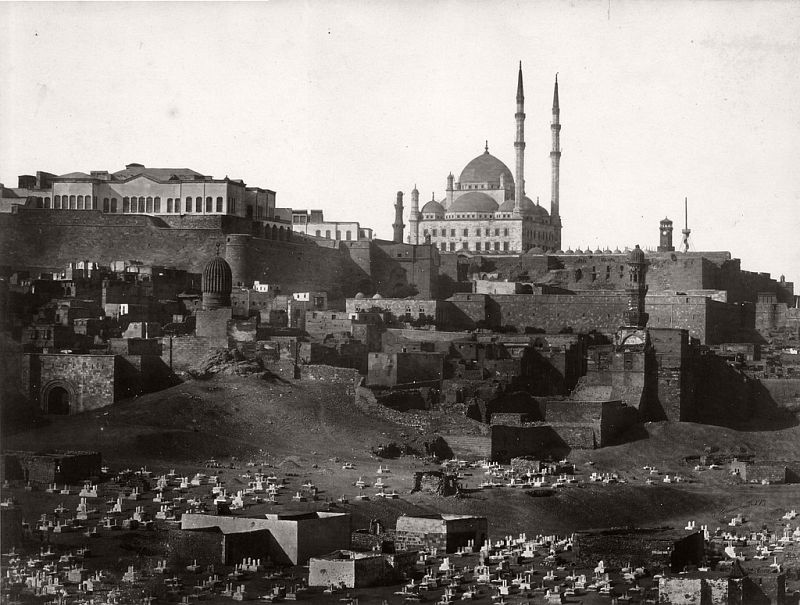

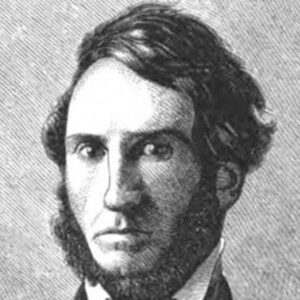

John Lloyd Stephens (1805–1852)

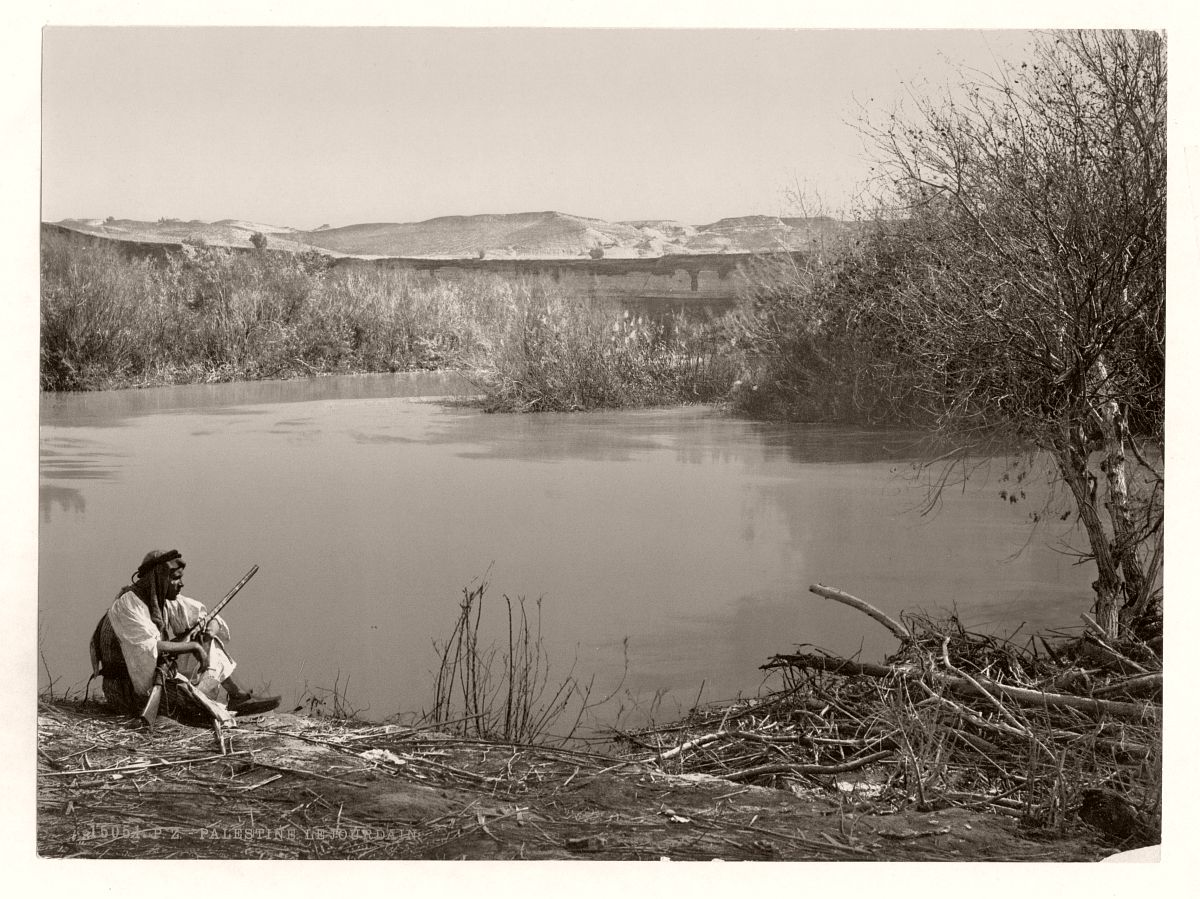

We can finally highlight the travels of John Lloyd Stephens from the USA to Egypt up to Jerusalem. John Lloyd Stephens (New Jersey, 1805 – New York, 1852) graduated at Columbia University in 1822, and, after studying law at Litchfield, Connecticut, and New York, was called to practice. He practiced his profession for eight years in the latter city, at the same time figuring occasionally as a public speaker at meetings of the Democratic Party, of which he was a warm supporter. When his health became impaired, he undertook a journey to Europe to recover, in the year 1834. He then decided to extend his travels to some parts of Asia and Africa along the Mediterranean. He wrote a series of letters describing his journey, which appeared in Hoffman’s “American Monthly Magazine.” When he returned to New York in 1836 he found that these letters had been the most popular feature in the journal. This fact led him to give a more detailed account of his travels, publishing “Incidents of Travel in Egypt, Arabia Pertain, and the Holy Land” (2 vols. New York, 1837.)

We can finally highlight the travels of John Lloyd Stephens from the USA to Egypt up to Jerusalem. John Lloyd Stephens (New Jersey, 1805 – New York, 1852) graduated at Columbia University in 1822, and, after studying law at Litchfield, Connecticut, and New York, was called to practice. He practiced his profession for eight years in the latter city, at the same time figuring occasionally as a public speaker at meetings of the Democratic Party, of which he was a warm supporter. When his health became impaired, he undertook a journey to Europe to recover, in the year 1834. He then decided to extend his travels to some parts of Asia and Africa along the Mediterranean. He wrote a series of letters describing his journey, which appeared in Hoffman’s “American Monthly Magazine.” When he returned to New York in 1836 he found that these letters had been the most popular feature in the journal. This fact led him to give a more detailed account of his travels, publishing “Incidents of Travel in Egypt, Arabia Pertain, and the Holy Land” (2 vols. New York, 1837.)

Perhaps the first modern travelogues still to capture the imaginations of armchair explorers, the mid-19th-century bestselling books of Stephens read like the most inspired of novels, their poetic immediacy placing the reader square in the saddle of adventure. In this classic 1837 work – which Edgar Allan Poe praised for its “freshness of manner evincing manliness of feeling” – Stephens takes the reader on an evocative journey through the Middle East, from a visit to the pyramids of Egypt to encounters with enthusiastic locals and much more. Complete with all the beautiful original illustrations by English artist and architect Frederick Catherwood (1799-1854), this delightful book continues to enthrall adventurous spirits today.

Conversational and unpretentious, the book is a delightful narrative of the author’s year-long journey through the Middle East, incorporating detailed observations of such architectural marvels as the Pyramids, the temples of Karnak, the red-rock city of Petra and more, and offering charming accounts of a Turkish bath, how to catch a crocodile, the wardrobe of a Nubian damsel, a night in a tomb, the hospitality of the Arabs, desert horses, and Easter in Jerusalem.

Overall, travel literature, whether inspired by pleasure, pilgrimage, official duty, geographical exploration or profit, emerged as a prominent genre in virtually all times and cultures. Travel narratives mediated between fact and fiction, combining different a number of academic disciplines, literary categories and social codes, and raising issues concerning power and self- perception, cultural representation as well as imagination, all of which contributed to the promotion of interfaith dialogue and understanding.

References

Cox, Edward Godfrey. A Reference Guide to the Literature of Travel, including Voyages, Geographical Descriptions, Adventures, Shipwrecks and Expeditions. Seattle: U of Washington, 1935. Print. University of Washington Publications in Language and Literature, v. 9-10, 12.

Smith, Harold Frederick. American Travellers Abroad : A Bibliography of Accounts Published before 1900. 2nd ed. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow, 1999.

Burgin, Robert. Going Places : A Reader’s Guide to Travel Narratives. Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited, 2013. Print. Real Stories.

Robinson, Jane. Wayward Women : A Guide to Women Travellers. New York: Oxford UP, 1990.

[i] https://www.thecultureconcept.com/lady-mary-wortley-montagu-adventuress-woman-of-influence

[ii] https://en.qantara.de/content/rifaa-rafi-al-tahtawi-france-as-a-role-model