Articles

Exhibitions in Italy and Spain as a reflection of a crisis

Date of publication of the article: 30/11/2022

Year of publication: 2022

Article theme: Art, Human Rights, Immigration, Inmigration.

This article analyses a sample of temporary exhibitions that explore the effects of a geopolitical context marked by forced migrations on two historically and culturally linked northern shores of the Mediterranean: Spain and Italy. How do we see migrants? What is the role of artistic and curatorial practice in their representation? Can they be a tool in the fight against xenophobia, racism and Islamophobia? To what extent have these migrations influenced our way of exhibiting?

A historical journey through images

The massive arrival of thousands of migrants on the shores of the northern Mediterranean over the last forty years has had a great impact on society, which, when confronted with otherness, has generated a series of visions and images that condition our way of relating to the world and to art. Curators, artists and institutions have taken it upon themselves to collect these images and their creation processes to offer them to the public and thus be able to unravel them, dissect them, through artistic language, thus responding to their demands and concerns. The transience of these events makes them particularly susceptible to change. In order to analyse them, this article makes an appraisal of this curatorial development with a temporal and historical perspective.

The Exodus Trigger

The twentieth century was a century in which, thanks to advances in technology and human development, mobility reached previously unseen dimensions and speed, which, together with globalisation, has contributed to the fact that “any country can be a potential destination for migrants” (Domínguez Mújica and Dirk Godenau 2010, 59-122). But what drives people to leave their countries of origin? War, hunger, poverty, insecurity, lack of future prospects and the threat of climate change are some of the reasons. Europe has not been unaffected by this process either.

Spain and Italy, both located on the southern borders of Europe, have been two of the territories most sensitive to political and cultural changes given their strategic geographical position with respect to migratory control, especially since the 1990s. The two countries are historically and culturally linked, to a large extent, by the waters off their coasts: those of the Mediterranean Sea.

The end of the Cold War and the fall of the Soviet Union (1991) provoked a situation of instability throughout the world, especially in those countries that had remained under Soviet rule. Many were forced to leave their countries and others found the sea the only escape route.

History, art and temporality

While in 1991 the situation in Italy was already described as ‘chaos in the Mediterranean’ (The Economist, 14 May 2009), in Spain there was a shift in external borders and entry control for those considered ‘non-EU’, as a result of the Schengen agreements signed in 1985. From 1998 onwards, Spain began to attract large numbers of immigrants, at least until the 2008 crisis. On the other hand, the Italian press, and not only the press, from the beginning of the 1990s, began to pick up and capture the despair of the so-called “third world”, a world that offered no opportunities. Hope materialised in the journey, the greatest exponent of which were the large barges arriving on European shores. It is in this context that we find the first curatorial approaches made in both countries.

The multiplication of exhibition events and institutions dedicated to the organisation of temporary exhibitions reveal the public’s concern to open curatorial practice to new realities that transcend the West

The first of these was Biennale XLV (1993, Venice), curated by Achille Bonito Oliva, and whose new edition was inaugurated with the name Punti Cardinali dell’arte. The exhibition emphasised the importance of the values of coexistence and difference. In a new way, the idea of the “journey” associated with the “others” appeared as a tool and a renewing force in art. As usual, autonomous exhibitions were included, such as Passaggio a Oriente, which examined relations between the West and the East. It was not until almost thirty years later that the Venice Biennale organised an exhibition, Rothko in Lampedusa, centred on this ‘journey’, more specifically on the value of refugees.

To Spain, it arrived at the hands of the curators Mar Villaespesa and Corinne Diserens, in the space of the Strait of Gibraltar. The very artistic process of the interdisciplinary public art project, Almadraba (1997-1998), acted not as a means, but as a way of approaching the different geopolitical questions as a product in itself: “a group of visual artists who investigate the “spaces of conflict” […]; they call for the permeabilisation of the border space and resist the official cartographies, making the Strait an osmotic space” (Romero, G. Romero).

The fact is that the East, understood as a cultural and geographical exoticisation expandable to North Africa, became part of the cultural economy as a consumer good subject to Western hegemonies. This has given rise to a series of new aesthetic hierarchies in which the peripheral is trapped, stifling elements of colonialism. Faced with this, the museum needs to leave the canonical places to confront, directly and creatively, the space for the inauguration of a new ‘museum-world’ (Ianicello and Quadraro 2015, 93-94).

Along these lines, projects such as El Paraíso es de los extraños (Paradise belongs to strangers) (started in 1999/2000), carried out by the artist Rogelio López Cuenca, emerged: a solo exhibition that takes a historical journey, focusing on the representation of Muslims in Western Europe.

During this decade, another event definitively marked our vision and consequent representation of the “Others”, the attacks of 11 September 2001. It was at this time that Islamic fundamentalism began to gain great attention, generating an Islamophobic narrative/sentiment. In Spain, the situation was, and has been, even more complex, given that it was compounded by the symbolic burden of the historical phenomenon of the “Reconquest”: a discourse that delves into the subjugation of the “invading” Muslim populations, mainly from the Maghreb, by the “Spanish” Christians.

Along these lines, projects such as El Paraíso es de los extraños (Paradise belongs to strangers) (started in 1999/2000), carried out by the artist Rogelio López Cuenca, emerged: a solo exhibition that takes a historical journey, focusing on the representation of Muslims in Western Europe based on the gazes that determine the way we represent “strangers” with the aim of reversing these stereotypes. According to Joaquín Barriendos Rodríguez, the symbolic dimension of subjects in movement has to do “with the geopolitical processes and contexts in which new subjectivities are politically and culturally negotiated” (2007, 160). These codifications take place through the coexistence and relationship between different proximate identities.

Between 2013 and 2014, there was a recovery of migratory rhythms, following the democratic revolutionary processes initiated in North Africa and the Middle East, which led to regime changes in Tunisia and Egypt and civil conflicts in Libya and Syria. However, if we review the data, we see that, between 2014 and 2016, around half a million migrants arrived on Italy’s southern coasts, most of them from countries such as Nigeria, Eritrea or Somalia, while in Spain they continued to be of Maghreb or sub-Saharan majority.

Today, both economic and forced migration have not ceased and new conflicts have come to the fore. There are more than one million refugees (2017) and migrants arriving on European shores as a result of recent events, especially those associated with the Syrian war and others. According to UNHCR, there are now 21.3 million forced refugees (2016), 54% of whom are Syrians, Afghans and Somalis. Despite these figures, it was not until 10 June 2022 that a “migration pact” launched by the European Commission, which had been stalled for almost two years, was reached.

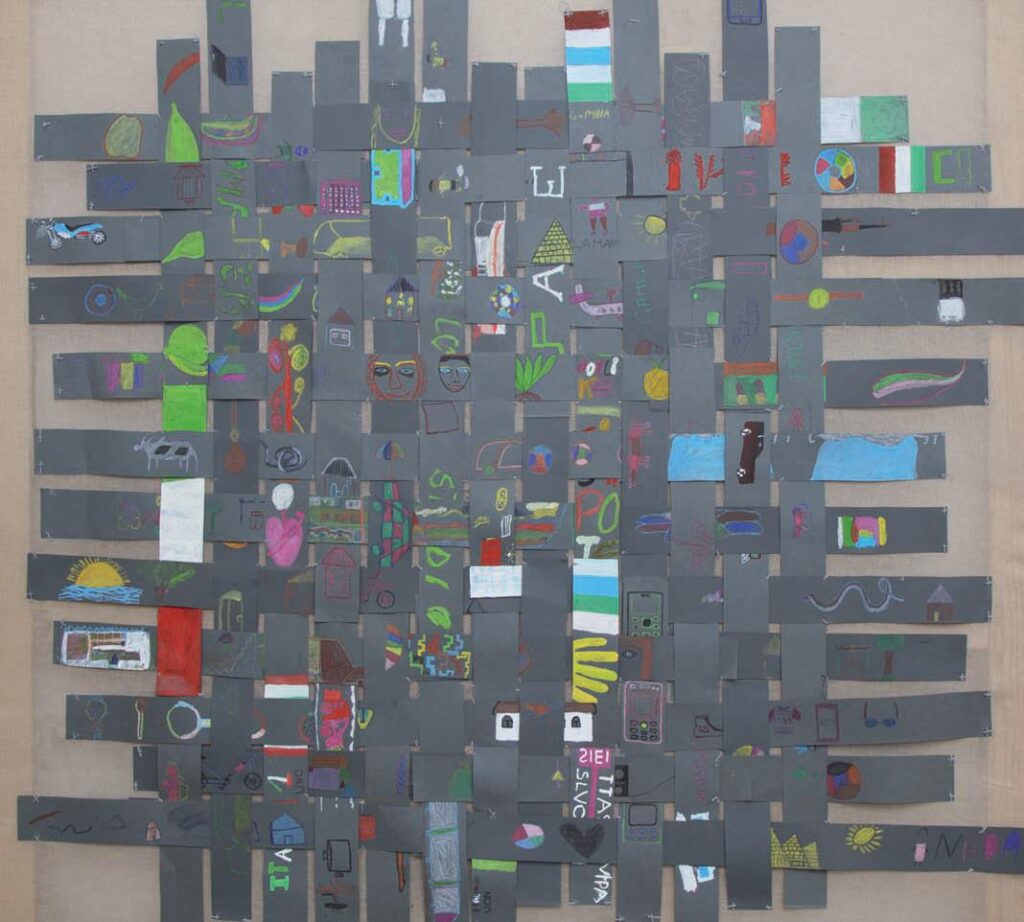

In Italy, the exhibition Odisseo, arriving alone exposed a reality that, until then, had not been dealt with: unaccompanied minors. Children and adolescents had the opportunity to tell their own odyssey from a personal perspective, through drawings and portraits.

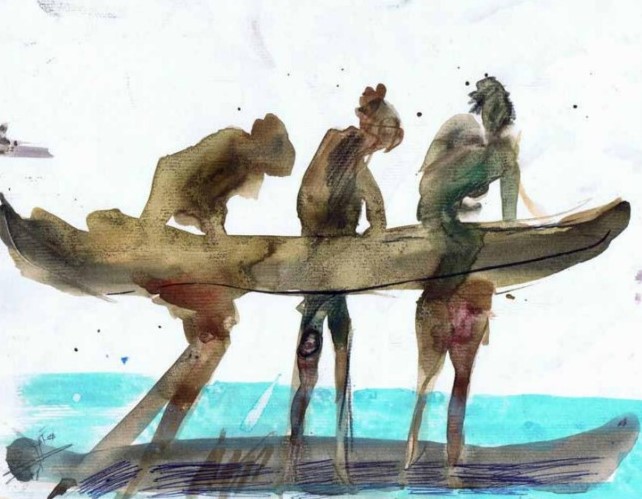

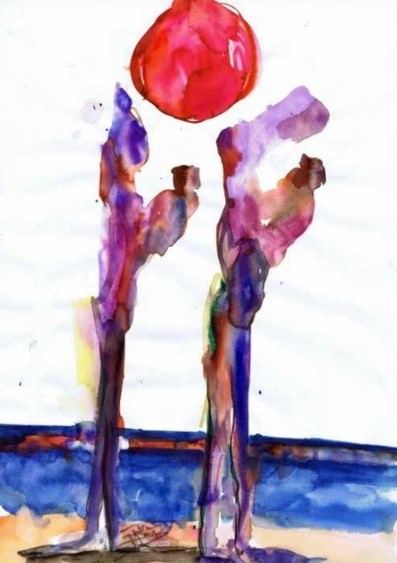

During this prolific last decade, projects such as Homenaje a los desaparecidos (2012), by the Lebanese painter, Matug Aborawi, have been presented, among many others, who, through his watercolours, has been responsible for portraying sub-Saharan immigration on its arrival at the Spanish coasts, a form of denouncing a dramatic reality. In 2016, the Instituto Valenciano de Arte Moderno held a group exhibition entitled Entre el mito y el espanto. The Mediterranean as conflict, where, through works and artists of different nationalities, it analysed the profound change in the vision and perception of the Mediterranean since the 19th century. That same year, in Italy, the exhibition Odisseo, arriving alone exposed a reality that, until then, had not been dealt with: unaccompanied minors. Children and adolescents had the opportunity to tell their own odyssey from a personal perspective, through drawings and portraits. In 2018, a group exhibition entitled Homes. Syrian stories through artists’eyes, which aims to act as a loudspeaker to give voice and shape to Syrian culture beyond its borders.

Conclusions

The multiplication of exhibition events and institutions dedicated to the organisation of temporary exhibitions reveal the public’s concern to open curatorial practice to new realities that transcend the West, to insert itself into new globalised trends from different perspectives: intercultural, historical, intersectional, denouncing… But we cannot forget that we find ourselves in a Western, white and privileged context. For this reason, curatorial attempts developed from the Western initiative, unless they seek self-criticism and a deepening of their own confrontation with otherness, are culturally condemned to fall into racist and xenophobic conventionalisms. We find that the value of non-Western works is initially established on the basis of our own stereotypes, which makes them mere colonial window dressing.

Art and temporary exhibitions are shown to be the ideal space to embrace the continuous changes and adapt to the demands and concerns of the public. Moreover, the mechanisms of representation, set in motion during the organisation of such an exhibition event, allow, through art and artistic practice, the dissection of our own experiences in contrast with the Other, but above all with ourselves; perhaps in the hope that the future will be kinder to those who set sail in order to reach European shores in the relentless pursuit of “prosperity”.

References

Barriendos, Joaquín. «El arte global y las políticas de la movilidad. Deslazamientos (trans)culturales en el sistema internacional del arte contemporáneo». LiminaR. Estudios sociales y humanísticos, Vol. V, nº. 1 (2007): 159-182.

Domínguez Mujica, Josefina y Dirk Godenau. «Las migraciones internacionales en el siglo XXI». En Migraciones laborales. Acción de la OIT y política europea, editado por Margarita IsabelRamos Quintana, 59-122. Albacete: Bomarzo, 2010.

Ianniciello, Celeste e Michaela Quadraro. Memorie transculturali. Estetica contemporanea e critica postcoloniale. Napoli: Università degli studi di Napoli, 2015.

Romero, Pedro G. «Almadraba». Acceso el 29 de mayo de 2022. http://www.fxysudoble.org/almadraba.html

The Economist. «A mes in the Mediterranean». The Economist, 14 de mayo de 2009, acceso el 6 de junio de 2022, https://www.economist.com/europe/2009/05/14/a-mess-in-the-mediterranean