Articles

Ten million euros to unearth the history of Islam in Europe

Article author: Bruno Martín - El País

Date of publication of the article: 14/12/2018

Year of publication: 2018

Article theme: Corán.

The Spanish researcher Mercedes García Arenal, specialized in the history of the Moorish, leads this important international research project, which will focus in the study of the existence and spreading of the Quran across Europe, throughout the centuries.

“It says a lot about a society the treatment it gives to its minorities,” says Mercedes García-Arenal (Madrid, 1950). The reputed historian He has been studying relations between Judaism, Islam and Christianity for years. “Better said, relations between Jews, Muslims and Christians,” he clarifies. He is interested in the moments and places of the past in which one of those groups was a minority with respect to others. Given García-Arenal’s effort to focus on the actors in the story, it is curious that his next big research project – the only one directed in Spain that has received this year an aid of almost ten million euros for the European Union, and the first of these characteristics that is granted to the Spanish humanities- will focus on the study of Quran, a sacred text.

In fact, the Quran is the tool with which García-Arenal and his companions seek to approach the different religious (and antireligious) factions that occupied Europe during the last millennium, and above all to the interactions of those groups. The project, called The European Quran, will be a six-year investigation that will document the dissemination, interpretations, translations and uses of the revealed book of Islam in Europe, from the Middle Ages to the Enlightenment. Its objective is to discover to what extent this text is imbricated, as a symbol of an alien people, in the intellectual and cultural history of the West on this side of the Atlantic. “More than what is now known or even suspected” is the hypothesis that García-Arenal works.

There was a cultural and religious hybridization that brings to light “very vital and intensely present issues in Europe today”, according to García-Arenal

Colonial Empires

The impression that one can not help but have is that Islam is in Europe only after the Second World War, since the colonial empires were dismantled and, above all, with immigration [reciente]”, He says. Nothing is further from reality. The involvement of Europeans with Islam is old and varied. Academic work has already documented a long history of cultural and religious hybridization that highlights “very vital and intensely present issues in Europe today,” says the historian. Beyond her professional interest, she sees in the project a tool to combat myths and disinformation about history and culture. “Knowledge is a very powerful weapon against ideology,” he argues.

Thee European Research Council (ERC) has awarded the daring initiative one of the prestigious Synergy Grants, its largest support by endowment and requirement, mandated to an international and multidisciplinary team, rarely outside the medical or natural sciences. In the last call 27 projects have been granted, of about 300 applications, and García-Arenal is the only one directed from Spain among them. It is also the first time that the Spanish humanities receive one of the many Synergy scholarships.

Thee European Research Council (ERC) has awarded the daring initiative one of the prestigious Synergy Grants, its largest support by endowment and requirement, mandated to an international and multidisciplinary team, rarely outside the medical or natural sciences. In the last call 27 projects have been granted, of about 300 applications, and García-Arenal is the only one directed from Spain among them. It is also the first time that the Spanish humanities receive one of the many Synergy scholarships.

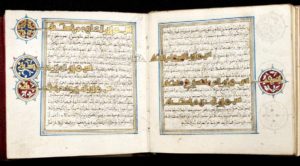

García-Arenal works in the Center for Human and Social Sciences of the CSIC, and collaborates in the project with Roberto Tottoli, of the Oriental University Institute of Naples (Italy), Jan Loop, of the University of Kent (United Kingdom), and John Tolan, of the University of Nantes (France). The first thing they will do, with their respective research teams, is to create a geolocated database of all the manuscripts, translations and texts relevant to the Quran that have been found throughout Europe.

A key tool

The database, which will be available in open access (free), is the star tool of the project, with which multiple investigations will be carried out. But the team part of knowledge already accumulated during years of study. They know, for example, that around the 12th century the first Latin translations of the Quran were made, used by Franciscan and Dominican monks to argue against Islam. “They tried to indoctrinate the Muslims and convert them … convince them that the Quran contains lies or contradictions,” explains García-Arenal.

However, in all subsequent centuries, this use of the Quran in Europe went into the background or disappeared altogether. It highlights the reappearance of the text in polemics between Christian factions, and later in the beginnings of secularization, wielded by atheists and agnostics as proof of a less dogmatic monotheism than Christianity. “The Protestant reform brought an extraordinary work of philological nature and translator,” says García-Arenal. “By denying the authority of the church, the biblical text acquires enormous relevance in Protestant Europe. [Los protestantes] they believe in the possibility that in some ancient texts of the Quran biblical passages may be found apocryphal or different from the composition of the Bible. “

“We have been, for a long time, assuming that being Spanish equals being a Catholic,” he summarizes. “It’s no longer sustainable.”

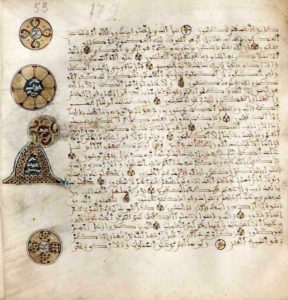

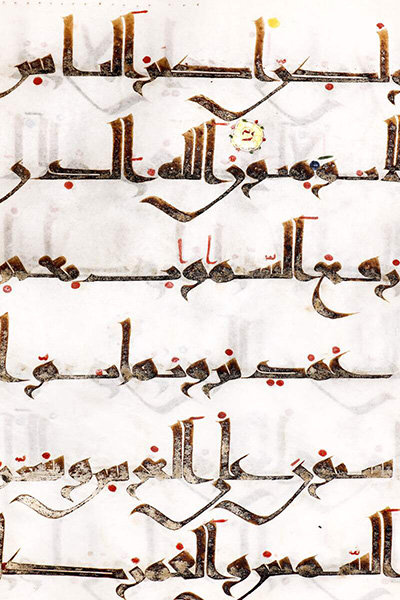

The European Quran puts the magnifying glass in these moments of history by identifying the European foci of learning, translation and printing in Arabic. “We are interested in seeing who paid the translators and how they made certain passages of the Quran say things that they were interested in saying.” To carry out this work, García-Arenal and his colleagues will analyze dozens if not hundreds of historical manuscripts: European Qurans glossed, illustrated, translated, printed and aljamiados (written in Spanish with Arabic alphabet). They will present a part of this formidable collection to the public through exhibitions confirmed in the British Museum (London), the Vatican Apostolic Library (Rome) and possibly in Budapest (Hungary) and the National Library of Madrid.

High school teachers

“We also have a lot of interest in sharing knowledge with secondary school teachers,” says García-Arenal. Although she highlights the importance of this type of education in neighboring countries such as France or the United Kingdom, the researcher recognizes that in the Spanish institutes “the curricula do not match the type of society that exists”. “We have been, for a long time, assuming that being Spanish equals being a Catholic,” she summarizes. “It’s no longer sustainable.” Spain, of course, has its own place in the religious history of Europe: the Iberian Peninsula was the only territory on the continent that hosted, in addition to very numerous Jewish minorities, Islamic minorities – legally recognized – until the end of the 15th century.

There is also “another mythical vision, and therefore ideological, that extols the fruitful imbrication with Hispanic Islam and medieval tolerance among the so-called three cultures.”

“The perception of Islam in Spain is very ideological,” says García-Arenal, speaking slowly. “There is a vision or a use of history that says that Spaniards now belong to the Christian roots, and that Al Andalus does not belong to our history.” For the defenders of that position, he says, “it is as if we had built ourselves as Spaniards to expel Islam.” On the other hand, he adds that there is also “another mythical vision, and therefore ideological, that extols the fruitful imbrication with Hispanic Islam and medieval tolerance among the so-called three cultures.”

García-Arenal recognizes that all academic work fits into a social context from which researchers not only can not isolate themselves, but also want to contribute (“not with political opinions”, but with data obtained by academic methods, he adds). She argues that the origins of the nation “are always mythical” and also ideological weapons against certain sectors of society that are still used today. “I am interested in the processes of hybridization and contagion, to see how one can not help but incorporate things from his enemy, even though he knows that he is fighting against it. I am interested in seeing how identities, said in the plural, are always mixed and fluid, “he shares.

García-Arenal recognizes that all academic work fits into a social context from which researchers not only can not isolate themselves, but also want to contribute (“not with political opinions”, but with data obtained by academic methods, he adds). She argues that the origins of the nation “are always mythical” and also ideological weapons against certain sectors of society that are still used today. “I am interested in the processes of hybridization and contagion, to see how one can not help but incorporate things from his enemy, even though he knows that he is fighting against it. I am interested in seeing how identities, said in the plural, are always mixed and fluid, “he shares.

In the end, her struggle is against the construction of identity on historical notions of purity, what she calls “essentialisms”. “It is messianic to think of a homogeneous society without conflicts, it is messianic to think that in the past this was a wonderful place where we were all one,” he says. “That seems to me like historical falsehoods, on the one hand, and dangerous myths, on the other. But my territory is that they are historical falsehoods. “

Source: elpais.com

Translated by Spainsnews.com