Articles

Islamic Madrid: heritage, identity, and the right to the city II

Article author: Daniel Gil-Benumeya

Year of publication: 2023

Article theme: 2023, Activities, Al-Andalus, Culture, Europa, FUNCI, Madrid.

Urban itineraries

Urban itineraries have been the main resource for the exploration, dissemination and valorisation of Madrid’s Islamic legacy. As in other cities, Madrid’s urban text is a palimpsest, whose ‘legibility resides both in the visible marks of the built space and in images and memories repressed or interrupted by traumatic events’ (Huyssen, 2001: 207). The urban itineraries seek to traverse Madrid’s Islamic history, showing its scarce visible remains, “finding the trace described by its absence” (Gordon, 2008: 6), and ultimately traversing the phantasmagoria that inhabit the city. The idea of phantasmagoria is applicable to Islamic Madrid in at least two ways. First, it expresses the way in which representations of the past produce effects on the management of both Islamic heritage and the Muslim presence in contemporary Madrid. Secondly, it is useful to narrate the unexpected and subtle way in which the vestiges of denied history manifest themselves in today’s Madrid: in the tangible, where one can glimpse how the Villa “has been guarding, unconsciously but jealously, the vestiges of its early history [. …] buried under the walls and foundations of later physiognomies” (Pérez de Tudela, 1989: 42), and in the intangible, as the Islamic presence can be associated with spaces and elements that, a priori, seem to have no relation to it. The evocation of all this gives rise to the ghost, which is but “one of the ways in which something lost, or barely visible, or seemingly not there to our presumably well-trained eyes, becomes known or apparent to us, in its own particular way, of course” (Gordon, 2008: 8). These itineraries are adapted to different circumstances and audiences, so that many of their characteristics – route, duration, analytical density, even language – are variable. There are, however, fixed itineraries, which are done on a regular basis.

The aim is to contribute to normalising the idea that diversity is a constituent element of society, and not just a recent effect of globalisation.

The first of these traces the traces of Andalusian and Mudejar Madrid. It evokes the history of the former, visiting some of its archaeological remains and its traces in the urban fabric, and also analyses its subsequent heritage treatment. And, at the same time, different places of memory of the approximately four centuries of minority Muslim presence in Castilian Madrid, of which few material traces remain, but there are some surviving traces in urban planning and toponymy, as well as stereotyped graphic representations (Gil-Benumeya, 2022: 114-118). The evocation of the Mudejar community is particularly interesting for reflecting on diversity, mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion and the agency of minority groups, due to their transcultural characteristics, their relationship with power, their political participation or the fact that they played a leading role in what could be described as the first documented strike in Madrid against segregation measures (Jiménez Rayado, 2016).

The second itinerary is entitled “El otro Madrid de los Austrias: moriscos, esclavos, renegados y cautivos” (The other Madrid of the Habsburgs: Moors, slaves, renegades and captives). The adjective ‘other’ suggests that the route takes place in a relatively well-known urban area and historical period – because they constitute an icon of Madrid’s past and also a ‘charismatic period’ of Spanish nationalism (Batalla Cueto, 2021: 225), as well as an important tourist asset – but it is executed from an unprecedented perspective: that of subaltern groups whose presence has been erased from historical representations and is practically absent from urban traces as well. The itinerary therefore exploits various avatars of the Islamic in Madrid society in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and its outstanding feature is the fact that it is partially based on primary archival sources – such as the trials of the Inquisition in Madrid – from which some of the places and stories that are evoked along the route are located. The experience of this itinerary, which passes through a “familiar” space by superimposing an unpublished narrative on it, and which therefore illuminates the territory and history in a different light, has shown that the notion of phantasmagoria is particularly pertinent (Gordon, 2008).

This itinerary has a variant, which to date has been developed only occasionally, entitled “El barrio de las otras letras”. Like the previous one, it takes place in a space strongly related to the Habsburg period and to the symbolic reserves of Madrilenianity, the so-called “Barrio de las Letras”, but it mainly exploits literary and biographical texts that show the traces of Islamic otherness reflected in the world of the arts and letters of Madrid’s Golden Age, as well as in certain Muslim views of the Madrid of the time.

There is a third common itinerary, which explores the Andalusian and Mudejar imprint in the Community of Madrid (CAM). This is a more complex and costly route than the previous ones, which is why it is to date the only one in the Madrid region, potentially offering many more possibilities for exploration. As has been pointed out, there are variants and adaptations of these itineraries to the needs of specific groups, including routes designed specifically for educational environments, especially secondary schools and universities. In broad figures, and taking into account the hiatus caused by the covid19 pandemic and subsequent limitations, between 2017 and 2022 approximately ninety urban routes and seven interurban routes were carried out, with a participation of approximately 1100 people in the former and 165 in the latter[1].

Academic synergies: research, teaching and documentation

CEMI bases its activities on scientific knowledge of Madrid’s Islamic history and heritage, keeps abreast of ongoing research, works with most of the specialists in this period – who are formally attached to CEMI as collaborators – and carries out some original research. That said, it is also true that CEMI’s research and/or academic production in the strict sense has been secondary to dissemination, urban exploration and institutional synergies. On the one hand, CEMI faces the shortcomings of an initiative that arose from the civil sphere, neither institutional nor business, whose material resources are discreet, and which therefore cannot, so far, sustain on its own (or through its foundation) long-lasting and/or large-scale research projects. On the other hand, CEMI has worked with the idea not so much of hosting such projects in itself, but rather that its activities, in the medium and long term, should contribute to research. This is both through the social, academic and institutional interest that may result from the dissemination work and through the generation of resources and tools for research and, above all, through the configuration of a new object of research, which would be Islamic Madrid in the long term, and which until now has been fragmented among various disciplines.

The substantive academic presentation of this new object of study was the I Interdisciplinary Congress on the History and Memory of Islamic Madrid, co-organised by CEMI and the Complutense University with the support of various institutions in May 2021. The event aimed to share knowledge about the historical Islamic presence in Madrid and its region and to reflect on the state of its tangible and intangible heritage, through the eyes of specialists in different areas, as well as institutional and civil society actors[2]. Subsequently, other initiatives and academic synergies have been launched, among which we can highlight the interdisciplinary teaching innovation project IslaMad, developed at the UCM in 2022-2023[3] and training programmes for first and second cycle teachers in the field of the CAM. Courses and materials on the teaching of Islamic heritage for heritage guides and interpreters have also been created.

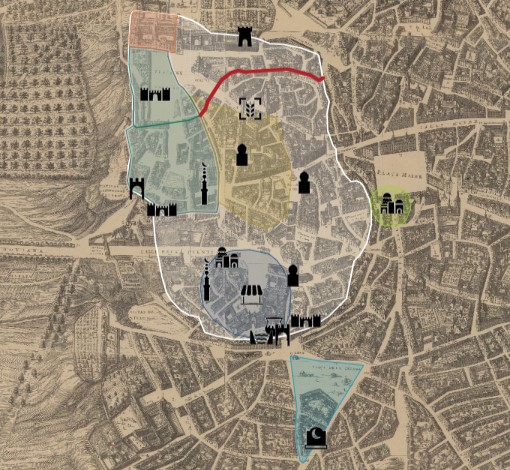

In terms of documentation, one of the initial aims was to bring together sources of all kinds that could be useful for research on Islamic Madrid, both primary and secondary, providing the reference and, where possible, the document in open access. The result is, for the moment, a simple, but scalable, database to be consulted through the web. Efforts have also been made to identify and systematise other resources useful for research, such as archival databases or historical cartography. In September 2022, the creation of a digital topographic map of Madrid with the sites of the Andalusian and Mudejar periods[4] was completed, with the aim of making it a reference source both for research and for the surveillance and protection of heritage. Finally, more recently, a series of digital reconstructions of missing infrastructures and sites have been undertaken, with the aim of experimenting, in the future, with augmented virtual reality applications applied to teaching and urban itineraries.

Institutional synergies

CEMI’s activities have sought to involve local administrations – municipal and regional – in the patrimonialisation of Madrid’s Islamic legacy, as it is they who have the greatest competence not only in matters of heritage, in the strict sense, but also in the production of “conceived space” (Lefebvre 2013: 16), that is, in the application of urban planning policies that regulate the uses and representations that can occur in public space. And, therefore, they have a direct responsibility in facilitating the coincidence of the multiple voices, manifestations and expressions of the city (Carrión, 2007: 83). In this sense, there have been channels of dialogue and collaboration with the CAM, through its Directorate General of Cultural Heritage, but above all with different bodies of Madrid City Council.

Ramadan Nights, 2018

Ramadan Nights, 2018Institutional collaboration with the Madrid City Council began during the 2015-2019 legislature through the Nights of Ramadan festival, which was then part of the city’s cultural agenda. Within this framework, a first experiment of urban itineraries was carried out (2017) and an informative work was produced to be published and distributed free of charge by the City Council (Gil-Benumeya, 2018). These collaborations served as a starting point for a sustained dialogue with the municipal authorities, whose objectives have been, on the one hand, to achieve a greater investment of resources and facilities in the research, protection and dissemination of Madrid’s Islamic heritage, and on the other, to enable forms of symbolic construction (Carrión, 2007: 84) of urban space with the aim of making this Islamic heritage visible as part of the city’s heritage and collective identity. These demands led to a series of contacts and collaborations of varying character and fortune, which have lasted through two legislatures of different political persuasions, without the change from one to the other having led to major differences. One of the results sought was the possibility of creating a permanent centre or infrastructure for the enhancement of Madrid’s Islamic heritage, which has not materialised, but neither has it been closed as a possibility. On the other hand, several agreements have been established with municipal entities that have allowed the landscaping and informative intervention in two historic locations – the Emir Mohammed I Park and the Almond Tree Garden -, the beginning of the heritage recovery of hidden Andalusian remains and the collaboration with the San Isidro Museum.

The legacy of the Andalusian period seems to arouse more interest in the administrations than the Mudejar or Moorish, possibly due to a historical schematism that fails to perceive the existence of the Islamic period in Madrid beyond the 11th century.

The possibilities for intervention in urban nomenclature were also explored during the 2015-2019 legislature. The names of public roads – as well as the evocations that are made on them, in the form of monuments, commemorative plaques, etc. – reflect the official narratives of history (Carrión, 2007: 85) and contribute to sustaining social representations of history which, in turn, legitimise various political and social mechanisms (Liu and Hilton, 2005: 539). Intervention on nomenclature and evocations is thus a form of symbolic construction of public space. Taking advantage of the impetus given during the aforementioned legislature to changing the names of public roads in order to comply with historical memory legislation and increase the evocations of characters linked to subaltern social sectors (women, in particular), the possibility of increasing toponymic references to Islamic Madrid and Al-Andalus was explored with the same reasoning. But the municipal response was reluctant. The Círculo Intercultural Hispano-Árabe (CIHAR), with the same idea, sought some form of monumental commemoration of the astronomer Maslama al-Maŷrīṭī and only succeeded in having ‘Al Mayriti’ added to the name of Maslama’s small square.

Islamic Madrid and tourism

Another sphere of action linked to institutionalism is tourism, given that local administrations, just as they play a central role in the processes of heritage activation, are also the main agents of tourism promotion. Tourism, and consumption in general, is a powerful activator of heritage repertoires, even if the motivation is none other than commercial interest (Prats, 1997: 41-42). The question that arises then is to what extent it could perform such a function in relation to Islamic heritage repertoires. Given their modesty in material terms, one possibility is to link them to a broader offer, such as that aimed at so-called halal tourism (for Muslim visitors), which is not very well developed in Madrid. In this way, Islamic heritage could serve for (and benefit from) a potential building of the Madrid city brand as a Muslim-friendly destination due to its Islamic origin and heritage. It has been shown that city brands, which seek to enhance the capacities of the territory through the creation of induced images and the promotion of differentiating features, generally for tourism, can generate multiplier effects in other spheres, including ‘all political, economic and cultural activities where identity is involved’ (Calvento and Colombo, 2009: 266).

FITUR 2023

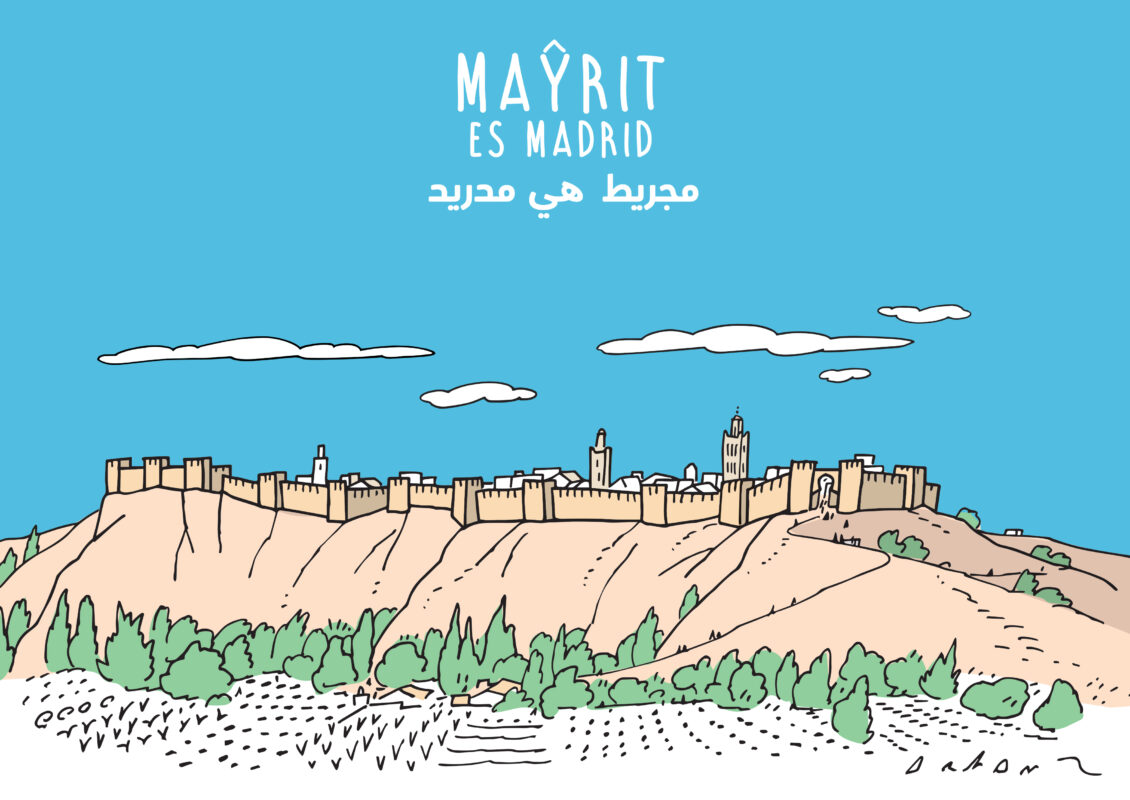

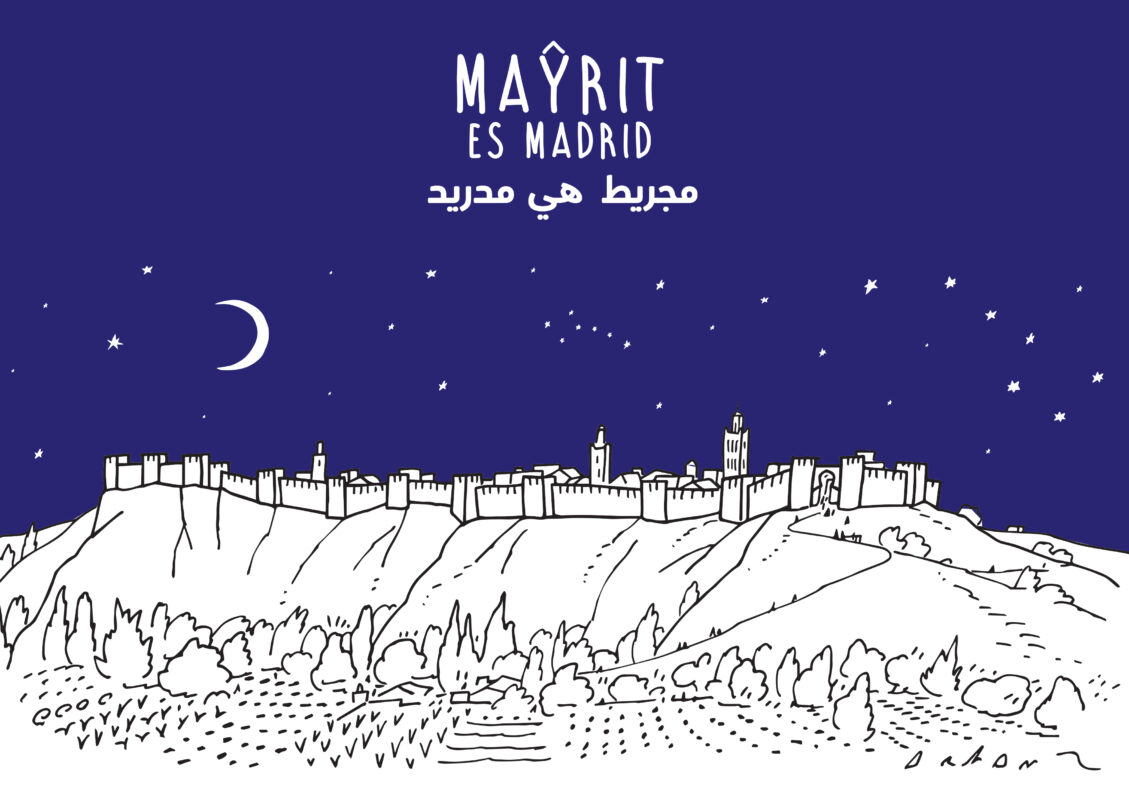

FITUR 2023On the other hand, one of the problems with tourism is precisely that what makes it attractive as a tool for heritage activation (transformation of heritage into a commercial asset, revitalisation and creation of imaginaries) is the same thing that makes it potentially destructive of public space and of heritage itself, when it is considered non-capitalisable. In Madrid, and especially in the city centre, it is clear that public space is managed at the pace of private mercantile action (Carrión, 2007: 79), and that even when mercantilisation uses a certain celebration of diversity as a resource, living, local expressions of diversity are gradually displaced from public space (Kingman Garcés, 2004: 31). With all these reluctances and doubts, the attempts in this field have led to the participation of CEMI and FUNCI in the FITUR fair and other tourism events, and in the occasional collaboration with municipal tourism authorities, for example in the inclusion of guided tours in tourist agendas, in meetings on halal tourism or in the drafting of a brochure dedicated to Muslim Madrid, by the public company Madrid Destino (2019)[5]. They have also led to experimentation with a label called Eco Halal Value, aimed at developing sustainable cultural tourism. Within this framework, they have also experimented with the creation of iconic references of Islamic Madrid, similar in concept to those usually used in tourist merchandising products, to represent the territorial identity of city brands (Calvento and Colombo, 2009: 266). To this end, different recreations of characters, motifs and spaces of Islamic Madrid have been created, accompanied by the legend ‘Maŷrit es Madrid’, in Spanish and Arabic, which have been printed on different media:

Recreation of Maŷrīṭ by day. Design by Olga Pérez (FUNCI) based on a drawing by Jorge Arranz. Image provided by FUNCI.

Recreation of Maŷrīṭ by day. Design by Olga Pérez (FUNCI) based on a drawing by Jorge Arranz. Image provided by FUNCI.

Recreation of Maŷrīṭ by night. Design by Olga Pérez (FUNCI) based on a drawing by Jorge Arranz. Image courtesy of FUNCI.

Recreation of Maŷrīṭ by night. Design by Olga Pérez (FUNCI) based on a drawing by Jorge Arranz. Image courtesy of FUNCI.

The difficulty that arises is to think about how the Madrid public could establish an iconic relationship between these images and Madrid, given that they evoke a history and heritage elements that most people are unaware of.

Other activities

Other types of activities have been developed, which would be difficult to detail here, so we will only give a few examples. Several of them could be included in the generic field of dissemination (talks, press, social networks, etc.), while others are of a more singular and discontinuous nature. In terms of dissemination, CEMI has a website and a presence on social networks, and has promoted and/or published articles both for dissemination and academic and journalistic purposes, as well as the book Madrid islámico: la historia recuperada (Gil-Benumeya, 2018), of which a second enlarged edition was published in 2020 – with versions in English and Arabic – sponsored by the Qatari publishing house Dār al-Ṯaqāfa. The success of the dissemination, however, depends less on its own resources than on the echo that some activities – such as those carried out in collaboration with Ramadan Nights, for example, and disseminated by the local cultural agenda – have been able to have in the general media, and the multiplier effect of these. We can cite as an example programmes with large audiences such as the special dedicated to the origins of Madrid in the programme Desmontando Madrid (Telemadrid, February 2021), which in turn attracted the interest of other media, both Spanish and foreign.

Photo: Telemadrid

Photo: TelemadridThe conference or talk type activities, on the other hand, are usually held at the request of various groups (associations, schools…) and their subject matter usually deals with different aspects of the history and heritage of Islamic Madrid, adapted to the demands of different audiences. These activities are generally well received, and we only mention, by way of anecdote, an adverse result in the case of a talk held in May 2019 to celebrate the coincidence of the local festival of Saint Isidore with Ramadan, and which aimed to discuss the hypothesis of the syncretic Islamic-Christian character of the figure of Saint Isidore (Fernández Montes, 1999). This activity served to prove the existence of certain religious red lines, as it was vehemently boycotted by a large group of people who accused the speakers of wanting to ‘Islamise’ the patron saint of Madrid (Gil-Benumeya, 2019). There have also been synergies with various civil society organisations related in one way or another to the objectives of the project. By way of example, since 2020 CEMI has been part of the association Madrid, Citizenship and Heritage (MCyP), and also collaborates with the Spanish National Committee of ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites). With both entities and with the NGO Islamic Relief, in 2020 it presented a project based on Madrid’s Islamic heritage for the European Commission’s Rights, Equality and Citizenship Programme. Likewise, it often participates with content related to Madrid’s Islamic heritage in different events on the cultural agenda. For example, in the V Encuentro de Cultura y Ciudadanía (2019), with a project entitled De Maŷrit al huerto, to relate the creation of urban gardens, which was developed during the 2015-2019 legislature, with Andalusian agricultural knowledge and Madrid’s own agricultural and water heritage; in the ICOMOS International Day of Monuments and Sites (2020) with a video produced during the confinement on Islamic Madrid; and in the II Festival of Public History (2022).

Conclusions

In conclusion, it is worth asking about the extent to which this initiative has been successful and the limitations it faces, as well as some of the objections that can be raised. In theory, the social impact of a project should be measured in terms of the degree to which it achieves its objectives. However, as it is not an academic or business project, nor is it publicly funded, nor does it have any other format that would require it to account for its impact in order to justify its interest, and eventually the money invested in it, the CEMI project has not developed formalised systems for measuring its scope and impact, nor a timetable against which to evaluate results. Some derived products, such as the teaching innovation project launched for the 2022-2023 academic year and others submitted to various calls for proposals, have been developed. But, in general terms, it is an initiative that has attached as much importance to the process and the reflections it gives rise to as to the potential effects, and understands that these will ultimately be verifiable above all in the medium and long term.

However, if the way in which a project interacts, directly or indirectly, with all the potentially interested actors can give an idea of its impact, CEMI has had fruitful contacts and collaborations, as mentioned above, with various academic, associative, institutional, media and, to a lesser extent, business actors. As for the latter, effective cooperation channels have also been established with the two local administrations involved (City Council and Community), in legislatures of different parties, and also with different political forces, in government or in opposition. FUNCI’s experience and extensive network of contacts has had a lot to do with this rapid multiplication of interactions with such diverse actors. Administrations have shown a cautious interest: they have favoured or given the green light to collaboration with certain initiatives, but have been more reserved with others. The Andalusian legacy seems to arouse more interest in the administrations than the Mudejar or Moorish legacy, possibly due to a historical schematism that does not perceive the existence of the Islamic in Madrid beyond the 11th century, or does not sympathise with the opportunity to look at later history through that prism. The connections with the Muslim presence in present-day Madrid seem to raise more caution.

Without prejudice to the fact that, as has also been pointed out, the capacities for effective influence of such a project, fuelled by more enthusiasm than material means, are limited, we believe that at least two of CEMI’s lines of action have found ways of development. Undoubtedly, it has succeeded in disseminating at least part of the historical Islamic legacy beyond academic circles. It has also contributed to research, the updating of the state of the art and the configuration of Islamic Madrid as an object of interdisciplinary study. The second line, which has to do with reflection on history and memory, has accompanied the above efforts in various ways: in urban itineraries, in application to teaching, in interventions in academic and extra-academic spheres and in publications.

There is also a specific debate on the uses of the “myth of Al-Andalus” as an alleged space-time of coexistence, with guidelines that consider that myth, as an element that serves above all as an element that justifies states of affairs, is in principle alien to historical truth.

The third line of the project, which has to do with the way of linking past and present, is more complex to evaluate. On the one hand, the question arises as to whether the mobilization of the past in relation to the present can be done without falling into a manipulation of history, into a presentist narrative. And, on the other hand, the question also arises as to whether this invocation of the past, in any case, can really have any transforming effect on the present, taking into account, moreover, that Muslim organizations do not mainly make demands for symbolic recognition (Salguero and Griera, 2022: 109). This is an open line of reflection, in relation to which we can bring up some recent positions of the existing debate on the history and memory of Al-Andalus. Eduardo Manzano Moreno (2020), for example, affirms that vindictive historiography -that which seeks to find arguments in the past for the present- contributes, although it pretends the opposite, to a way of approaching history that is substantially conservative, and of which conservative historiography will always know how to make better use. And, moreover, he considers that it is a “manifestly useless effort to face the multicultural challenges of the present” (Manzano Moreno, 2020: 55). In the first place, because it requires thinking from false immanences and historical subjects that would extend through the ages, linking past and present, and secondly because, in any case, nothing guarantees the triumph over the hegemony of conservative thought. And he gives as an example that the great advance of the last decades in the knowledge about the Andalusi past “has not provoked a generalized acceptance of its relevance or the need to incorporate it” (Manzano Moreno, 2020: 49). On the other hand, Emilio González Ferrín (2020) defends, from a historiographical position that has been the subject of intense controversy, but which we consider to some extent separable from the issue that now concerns us, that historians must fight the battles of the present and counteract the great systems of pseudo-historical dissemination, in order to help “feed a cosmopolitan present by showing a past that was no less so” (González Ferrín, 2020: 139). There is also a specific debate on the uses of the “myth of Al-Andalus” as an alleged space-time of coexistence, with guidelines that consider that the myth, as an element that serves primarily as an element that justifies states of affairs, is in principle alien to the historical truth (Manzano Moreno, 2013; Torrecilla, 2020); and others that, on the contrary, defend the part of truth that resides in the myth and its validity to think present and future coexistence (González Alcantud, 2014; Hirschkind, 2020).

The project that we have been presenting in these pages does not have, in this aspect, a conclusive theoretical position, and it recognizes itself to some extent in arguments of one kind or another. It is a project that is embedded in the tradition of situated knowledge and that aims, from its modest position, to help change certain social representations of history and the way in which these influence the present and help to think about possible futures (Liu and Hilton, 2005: 549-550). But he also considers that this task involves, precisely, dismantling the pseudo-historical narratives and the “labyrinth of supposed certainties” (Manzano Moreno, 2020: 53) that underpin exclusionary discourses. By evoking the presence of Islam in Madrid not only in the origin and in the present -the extremes that carry more weight in the social representations of history (Liu and Hilton, 2005: 539)-but also throughout most of the centuries between one and the other, the aim is to show that Madrid society (like Spanish society) has historically been much more complex than the narrative it has constructed about itself, and thus to contribute to normalizing the idea that diversity is a constituent element of the social, and not just a recent effect of globalization. The relationship between past and present Muslims in Madrid, on the other hand, is not made from the identification of any “historical subject” that would have spread over the centuries (Manzano Moreno, 2020: 54), but from the need to respond to a public discourse that advocates “an opposition of medieval roots against an Arab and Islamic identity considered alien both then and now” (Manzano Moreno, 2020: 52), even when the human sustenance and the concrete contours of that identity have mutated. In this process, the intention is not so much to claim for Islam “quotas of authorship” (González Ferrín, 2020) in the history of Madrid, or to sustain the legitimacy of its presence based on its historical roots, although, undoubtedly, the project can lend itself to this and could give a positive convivial result. The ideal, rather, would be to foster a sort of disidentification with identity narratives, to contribute to give “ontological status” to the changing hybridization that constitutes social reality (Núñez García, 2019) and from which are built, by exclusion, the closed categories that structure our present and our vision of the past.

Links

Consult the complete bibliography of the article here Islamic Madrid: heritage, identity and the right to the city I

Notas

[1] We owe these estimates to Irene Suárez and Rafael Martínez, CEMI’s advisor for cultural itineraries and architect of the interurban routes.

[2] See https://madridislamico.org/i-congreso-interdisciplinar-de-historia-y-memoria-del-madrid-islamico2/. The speeches of the congress, which was semi-face-to-face, can be viewed on the Fundación de Cultura Islámica’s YouTube channel.

[3] See https://www.ucm.es/islamad

[4] See https://madridislamico.org/mapa-interactivo-en/

[5] See https://www.esmadrid.com/sites/default/files/el_madrid_musulman.pdf [accessed 21/09/2022].