Articles

Ibn Jubayr: An Andalusian Traveller for Penance

Article author: Dr Mohamed Chtatou

Date of publication of the article: 23/12/2021

Year of publication: 2021

Article theme: History, Literature, Rihla.

Between the eleventh and the fifteenth century, three great groups of civilizations were in contact around the Mediterranean Sea: to the north-east the Byzantine Empire, to the east and south the Muslim world, and Western Christianity to the northwest.

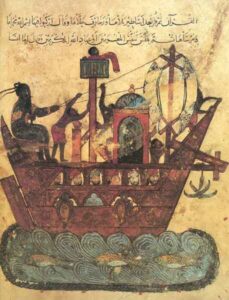

In the Middle Ages, navigation on the Mediterranean Sea also allowed for peaceful contacts between the three civilizations that border it. The commercial exchanges dominated by Italian merchants facilitated the circulation of knowledge and Arab and European travellers undertook long and gratifying journeys to discover other cultures and civilizations and, as such, provided a rich literature of geographical, cultural, and anthropological interest.

Who was Ahmad ibn Jubayr?

Ahmad ibn Jubayr (Abū al-Ḥusayn Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Jubayr al-Kinānī أبو الحسين محمد بن أحمد بن جبير الكناني ) was born in Valencia in 1145 and became secretary to the governor of Granada. In this way, he did not belong to the milieu of the ulamâ’ or the great merchants, but to that of the officials employed at court, with the aura that this could represent but also the risks of the position.

Ahmad ibn Jubayr (Abū al-Ḥusayn Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Jubayr al-Kinānī أبو الحسين محمد بن أحمد بن جبير الكناني ) was born in Valencia in 1145 and became secretary to the governor of Granada. In this way, he did not belong to the milieu of the ulamâ’ or the great merchants, but to that of the officials employed at court, with the aura that this could represent but also the risks of the position.

Thus, one day his master forced him to drink wine and, to atone for this fault, Ibn Jubayr decided to go on a pilgrimage to Mecca. Ibn Jubayr’s rihla, the prototype of so many others that followed, deserves to be studied in great length given its importance. It is an account of a hajj as a vehicle of guilt, a rihla of atonement i.e., kaffârah. Indeed, Ibn Jubayr was in the service of the governor of Granada, Abu Sa’id ‘Uthman b. ‘Abd al-Mu’min, employed as his secretary, and the governor, in a fit of fantasy mixed with arrogance and power, forces his unfortunate secretary to drink wine. Ibn Jubayr, intimidated, obeys but he is, afterward, both mortified and feeling guilty. In this regard, Ibn Jubayr’s translator says:

“The prince was [then] seized with a sudden pity, and overcome with remorse, had filled the cup seven times with golden dinars and poured them into the breast of his servant’s robe. The good man, who had long cherished the desire to fulfil the duty of the pilgrimage to Mecca, immediately resolved to atone for his impiety by dedicating the money to that end. “

Ibn Jubayr, thus, set out on the road to do penance and produced interesting writings that gained almost immediate popularity. His journey took him to many of the cities of the Middle East, where he commented on the topography and monuments as well as the customs and foibles of the local inhabitants. His work is at the confluence of religious, social, cultural, and humanistic interests; it gives us a vivid map of the East in the 12th century and of the political use of beliefs at that time.

Ibn al-Khatib describes him with great reverence and admiration:

كان أديباً بارعاً، شاعراً مجيداً، سنياً فاضلاً، نزيه المهمة، سري النفس، كريم الأخلاق، أنيق الطريقة في الخط. كتب بسبتة عن أبي سعيد عثمان ابن عبد المؤمن، وبغرناطة عن غيره من ذوي قرابته، وله فيهم أمداح كثيرة. ثم نزع عن ذلك، وتوجه إلى المشرق، وجرت بينه وبين طايفة من أدباء عصره، مخاطبات ظهرت فيها براعته وإجادته. ونظمه فايق، ونثره بديع. وكلامه المرسل، سهل حسن، وأغراضه جليلة، ومحاسنه ضخمة، وذكره شهير، ورحلته نسيجة وحدها، طارت كل مطار، رحمه الله.

“He was a brilliant man of letters, a glorious poet, a virtuous Sunni, honest of work, of excellent character and gracious manners, with elegant handwriting. He studied in Ceuta under the tutelage of Abu Said Uthman Ibn Abdul-Mo’men, and in Granada under many others from his relatives, for whom he wrote many poems in their extolment. He then went to the Orient, and along the way many debates and correspondences took place between him and a few authors of his time, correspondences which featured his proficiency and fluency. His composition is superior, and his prose is exquisite. His flowing words are pleasing and easy to understand; his exigencies are grand, his qualities are prodigious, famed around the world…”

His travels rahalât

Ibn Jubair made three trips to the Eastern territories. Only his first journey, made before the reconquest of Jerusalem by Saladin’s troops (1187), is the subject of a very dense account. It is a maritime expedition carried out from 1183 to 1185, motivated by the visit of Mecca. He successively discovered Tarifa, Ceuta, Sardinia, Sicily, Crete, Alexandria, and then, once he arrived in Egypt, he followed the usual route of the pilgrims through the Nile, Qus, Jeddah, to reach Mecca. After completing the pilgrimage in 1184, he joined the caravan of Iraqi pilgrims and visited Baghdad, Mosul, Aleppo, Damascus, Acre, Tyre before embarking for al-Andalus, after a stop in Sicily, completing his journey in 1185.

Thus, in February 1183, he set out for Ceuta, where he boarded a Genoese ship bound for Alexandria. On board, he learned of the fate of 80 Muslim men, women and children who had been kidnapped in North Africa and were about to be sold as slaves. Between Sardinia and Sicily, the ship was caught in a severe storm. He says of the Italians and Muslims on board, seasoned sailors, that they all agreed they had never seen such a storm in their lives. After the storm, they sailed past Sicily and Crete, before heading south and crossing the North African coast. By March 26, they had arrived in Alexandria.

He visited Cairo, went down to Middle Egypt, and crossed the Red Sea from the Egyptian port of Aydhāb to Jeddah. He performed the rites of pilgrimage and then piously visited Medina before heading to Kufa, determined to visit the heart of the Muslim world. From Kufa, he continued towards Baghdad and then Mosul. He follows the Tigris River before heading west to Harran – now in south-eastern Turkey – to arrive in Syria, Aleppo, Homs and finally Damascus. He then headed towards the coast, via Acre, crossing the territory of the Crusaders, to take over a Genoese ship towards Andalusia. When he reached Sicily, he was shipwrecked and stayed on the Norman Island for a few days before re-embarking in Trapani for Cartagena. He returned to Granada in April 1185, more than two years after his departure.

Alexandria, great city of Egypt

He wrote down his journey under the title Taḏkira bi-akhbār can ittifāqāt al-asfār, or “Relations of the adventures that occurred during the voyages.”

Obviously, the experience did not displease him, for he made another pilgrimage in 1189-1191 to thank God for allowing Saladin to reconquer Jerusalem, and then he took the boat again in 1217 for a third pilgrimage. Back in Egypt, he taught in Alexandria the same year, and it is there where he died.

We also owe him a small pilgrimage manual that does not belong to the genre of narrative but to that of guides, or manāsik, it is “the Epistle of the devotee’s instruction on the noble relics and pious rites” (Risāla ictibār al-nāsik fī ḏikr al-āṯār al-karīma wa-l-manāsik).

For Yann Dejugnat, the travel literature of Ibn Jubayr is dense and informative:

‘’Ibn Jubayr’s travelogue (rihla) is a well-known source for historians of the medieval Mediterranean. It has been praised for its quality and density of information and has been used extensively as a reservoir of data of all kinds. But the work itself, paradoxically, has not been the subject of much study. More precisely, the main flaw of the research is that it is approached with an “overly synthetic” approach, since it is too general, of which the generic use of the term “rihla” is symptomatic, insofar as it disregards the specificity of each travelogue and its precise context of elaboration. This genre would be marked, on the one hand, by an objectivity that would make it valuable as a testimony and, on the other hand, by an absence of any preconceived plan, a sign of the limited ambition of a work whose horizon would be limited to a simple individual experience. To these characteristics, Ibn Jubayr’s rihla would also add a narrow provincialism insofar as the Maghreb often appears as the country of reference. ‘’

Cities visited

In Egypt, his attention is drawn to the Alexandria lighthouse, the pyramids, the sphinx, or the temple of Akhmim. The Egyptologist Serge Sauneron commented from an architectural point of view his observations, judging them perfectly realistic. He also describes the pearl fisheries at Aydhāb, on the Red Sea, and with meticulousness the basins that punctuate the road from Mecca to Kufa. He also shows an interest in the urban infrastructures of his time, whose founders are praised: city gates, mosques, Sufi convents, madrasahs, baths, hospitals in small and large cities, especially in Damascus and Cairo.

In Egypt, his attention is drawn to the Alexandria lighthouse, the pyramids, the sphinx, or the temple of Akhmim. The Egyptologist Serge Sauneron commented from an architectural point of view his observations, judging them perfectly realistic. He also describes the pearl fisheries at Aydhāb, on the Red Sea, and with meticulousness the basins that punctuate the road from Mecca to Kufa. He also shows an interest in the urban infrastructures of his time, whose founders are praised: city gates, mosques, Sufi convents, madrasahs, baths, hospitals in small and large cities, especially in Damascus and Cairo.

He dwells on the functioning of hospitals and describes how teaching was carried out in the great mosques. In Mecca, he gives a measured description of the holy sanctuary.

While Baghdad – still the theoretical capital of the Muslim world – is described to us as a once glorious city but now in ruins while Damascus, and in particular the Umayyad Mosque, is the subject of a laudatory and precise description. Certainly, this is one of the cities from which Saladin led the counter-crusade. However, Yann Dejugnat has brilliantly shown that this tacit opposition between the two cities – Baghdad and Damascus -, as well as the systematic mention of Umayyad monuments in Aleppo or Ḥarran, for example, were part of a nostalgic re-investment in the Umayyad caliphate opposed to a disappointed impression of Baghdad.

He described Damascus in the following terms:

“May God, most high, guard it! Damascus, the paradise of the East, the point from which her radiant light rises, the seal of the countries of Islam that we have visited, the new bride that we admired after she had lifted her veil. She had adorned herself with flowers and herbs, she appeared in the green brocade dress of her gardens. She was eminently beautiful, sitting on the bridal seat, adorned with all her finery. Damascus is proud to have sheltered the Messiah and his mother – God bless them! – on a hill, a tranquil place, watered by living waters where a thick shadow extends and where the wave is like that of the Salsabîl in paradise. Its streams wind everywhere, its flowerbeds are crossed by a light, invigorating breeze. The city shows itself to whoever contemplates it in its beautiful radiance and says to him: “Come then to this place where the charm remains!” The ground of Damascus is so saturated with water that it would almost want to be dry, and the hard stones would almost cry out to you, “Stamp your feet, this is where you can do your ablutions with fresh water, and you can drink!” The gardens surround Damascus like the halo surrounds the moon, the chalice the flower. To the east, its green Ghouta stretches as far as the eye can see, and towards whichever direction one looks its dazzling splendour catches the eye. How right were those who spoke of Damascus to say, “If paradise is on earth, Damascus is there, and if it is in Heaven, Damascus rivals it and is at its height!””

Though he happily glimpses there three times the young caliph al-Nāṣir, then 25 years old, who later would give the caliphate its last flourish. Nevertheless, one must be reminded that after the fall of the Umayyads of Damascus, this caliphate subsisted in Cordoba and gave prosperity as well as real political power to Andalusia, from which Ibn Jubayr came. The traveller in his account – intended primarily for Maghrebi and Andalusian readers – makes a reading of the Umayyad legacy at a time when the Almohads were trying to capture Syrian memory.

Aleppo is a city of great importance, famous in all circumstances; it was courted by many rulers and is dear to the souls of men. How many battles it has unleashed, how many white blades it has brandished! Aleppo has an inaccessible fortress, which is distinguished by its impenetrable height. One of the reasons for the honour of this fortress is that in ancient times it was the hill on which Abraham al-khalîl, the friend of God, peace be upon him and Islam’s Prophet, sought refuge with his flocks. It was here that Abraham began to milk (yahlib) the animals and distribute their milk as alms. This is the reason why the city was called Aleppo (Halab).

In the fortress stands a venerable mausoleum dedicated to Abraham, where people go in prayer to ask for blessings. Among the qualities that are indispensable for the impregnability of the fortress is the water that gushes out from within it. Above the spring are two cisterns from which water flows, so that one never fears thirst. Food is also always kept inside the fortress. There are no more important and safe conditions than these two to guarantee the impregnability. Around the cisterns, on the side facing the city, are two fortified walls at the foot of which is a ditch where the water pours out and whose depth the eye can hardly see.

The impregnability and beauty of this citadel are greater than words can express. At the top of the walls are regularly arranged towers with commanding vantage points and majestic galleries into which arches open. All the towers are inhabited, inside are the apartments of the sultan and the residences of the royal dignitaries.

As for the city itself, it is imposing, built with care, of a stunning beauty, with large markets arranged in long rows so that one passes from one row of stores to another until one has seen them all. A wooden roof protects the markets, offering shade to customers. The beauty of these markets catches the eye and passers-by stop in amazement. The qaysâriyya (covered market) is like a garden with its many flowers and plants.

In the XIIth century, Palermo was the capital of the kingdom of Sicily, ruled by King William II, who was Christian. He described what he saw as follows:

“The most beautiful city of Sicily is the residence of its king; the Muslims call it the city of al Madina and the Christians Palermo; it is there that the Muslims live; they have mosques and the souks which are reserved for them in the suburbs are numerous. All the other Muslims live in farms, villages, and other cities, like Syracuse, etc. But it is the big city, residence of the of King William, which is the most important and the most considerable. […]

‘’The attitude of the king is extraordinary. He has a perfect conduct towards the Muslims; he entrusts them with jobs, he chooses his officials from among them, and all, or almost all, keep secret their names, or almost all of them, keep their faith secret and remain attached to the faith of Islam. The king has full confidence in the Muslims and relies on them in his affairs and of his concerns, so much so that the steward of his kitchen is a Muslim. […] Another extraordinary feature of him is that he reads and writes Arabic. “

Praise for Saladin

Ibn Jubayr lived at the time of the Crusades, however they do not appear in his account, at least not directly because he is not a historian, so he does not chronicle them, but the praise that Saladin receives from his pen for his actions towards the Crusaders gives a good idea of the state of mind of a scholar of the time. When he mentions the construction of the citadel and the wall of Cairo at the instigation of Saladin, he insists on the fact that it was Christian prisoners who were forced to carry out these constructions.

Of course, he is distressed when he sees Muslim captives reduced to the same extremes in Acre, in Crusader territory. His praise of Saladin is fuelled by the actions that Saladin took to stop Crusader operations in the Red Sea. He does not fail to point out that he saw Latin prisoners taken in the Red Sea and publicly displayed in Alexandria, just as he rejoices in having seen the Muslim troops return from the victorious attack on Nablus, laden with booty and captives. Nevertheless, he leaves a mixed description of the Latin territories because, on the one hand, he recognizes the correct treatment of Muslim peasants by their Christian lord – an impression highlighted by the historian of the Crusades René Grousset in the colonial era – and rants against a Maghrebi Muslim who converted to Christianity and, on the other hand, he often judges Latin customs severely, such as a marriage in Tyre which he witnesses.

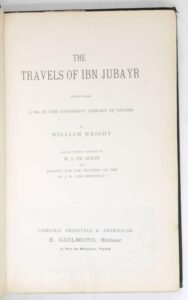

How did his work come to us?

The work was first known through the edition made by the Arabist William Wright – then 22 years old- It was then thought to be unique, but since then three other manuscripts have been discovered in Morocco. Moreover, soon after its writing by Ibn Jubayr, the work was read, so one of his disciples, al-Sharīshī (d. 1222), uses it in his commentary. As early as the fourteenth century, this account was plagiarized; for example, the Andalusian al-Balawī (d. 1364), who made a trip to the East, borrowed from it his descriptions of Alexandria, Cairo, Medina, and Mecca. And even Ibn Juzayy (d. 1326) – the scribe for whom Ibn Battuta (d. 1377) dictates his journey – borrows from him the description of Mecca and Medina, which Ibn Battuta seems to have forgotten. In the Maghreb, the traveller al-‘Abdarī (d. 1300) quotes him more than a dozen times. In Egypt, al-Maqrīzī (d. 1442), makes use of it in his description of Cairo. Later, al-Maqqarī (d. 1632) devoted a biographical note to him.

The work was first known through the edition made by the Arabist William Wright – then 22 years old- It was then thought to be unique, but since then three other manuscripts have been discovered in Morocco. Moreover, soon after its writing by Ibn Jubayr, the work was read, so one of his disciples, al-Sharīshī (d. 1222), uses it in his commentary. As early as the fourteenth century, this account was plagiarized; for example, the Andalusian al-Balawī (d. 1364), who made a trip to the East, borrowed from it his descriptions of Alexandria, Cairo, Medina, and Mecca. And even Ibn Juzayy (d. 1326) – the scribe for whom Ibn Battuta (d. 1377) dictates his journey – borrows from him the description of Mecca and Medina, which Ibn Battuta seems to have forgotten. In the Maghreb, the traveller al-‘Abdarī (d. 1300) quotes him more than a dozen times. In Egypt, al-Maqrīzī (d. 1442), makes use of it in his description of Cairo. Later, al-Maqqarī (d. 1632) devoted a biographical note to him.

Of this long two-year journey, Ibn Jubayr wrote an account, the Rihlat Ibn Jubayr (“The Voyage of Ibn Jubayr“), which was to become a classic of medieval Arabic literature. In this book he offers a suggestive panorama of the city of Aleppo.

Founder of a new literary genre

If the pilgrimage was practiced since the birth of Islam, it was not until the Middle Ages that it became an object of writing as the curious traveller could go listen to the different scholars that the chances of his peregrinations made him meet and finally make a rewarding list. Now, Ibn Jubayr regularly gives his opinion on his experiences and his meetings. He vituperates against the affronts of customs in Alexandria as well as the unscrupulous greed of people who take care of the pilgrims and rent them their services.

His work extends over the dangers and abuses that await the traveller. His narrative is autobiographical and retrospective, with a subjective personal point of view, claimed as is. It naturally follows the route borrowed, city by city, with a diarist’s accuracy. Its stages or events of which he witnessed are the subject of living descriptive digressions, where a sincere devotion is expressed. And this piety finds a singular expression by innumerable invocations to Allah and by the description of extreme emotions marked by tears.

He is indeed a devout Muslim who has an interest in secondary piety places. He lists the graves of saints or descendants of the Prophet in the places visited as the Qarāfa cemetery in Cairo, that of Al-Baqī in Medina or that of the companions of the Prophet in Damascus. He exalts the memory of all the holy characters of the past: he remembers Abraham in Harran, in Aleppo and Damascus, but the latter city has also seen Abel, Cain, the Messiah and his mother. In Mosul, he remembers Jonas. Koufa gives him the opportunity to mention the house of Noah, the oven at the origin of the flood in the Muslim tradition, but also the mosque where Ali Ibn Abi Talib was wounded to death. This inclination for the places of religious memories joined that of his contemporary Alī al-Harawī (1215) who wrote a reasoned account.

In Cairo, describing the public expressions of devotion on the part of the Sunnis and Shiites around the mausoleum of al-Husayn – the grandson of the prophet – that one touches, that one embraces, he testifies to a devotional heritage common to all Muslims. But we hear that its landmark remains maliki and the rigor Almohad. He takes a respectful look at the descendants of the Prophet, whatever their current social status. This attraction for modern piety – the one that is contemporary – is marked by a solicitude for the Sufis, the ascetics and by the eulogy of the charity that the Muslim must show for his coreligionists. Let’s not forget that starting from the twelfth century, popular devotion and Sufism became an integral part of the social expression of Islam. Conversely, he criticizes hypocritical or dishonest Muslims, denouncing those of Baghdad. He also blames the powerful who abuse their power and encourage prebend practise.

He also makes a meticulous and sometimes caustic description of the rites and solemnities that surround the pilgrimage. But we discover a sincere naivety when he exalts the virtues of Mecca whose products he considers (honey, meat, fruits) as the best of the universe by the grace of the place.

His rigorous piety makes him castigate popular credulity and he never refers to astrology, although he is echoing prodigies announcing political changes. In this case, the collapse of a statue in Cairo watching towards the East coincided with the arrival of the army of which Saladin was the commander. The population therefore thought that the collapse of another statue looking to the West would announce the arrival of conquerors from the West. For Ibn Jubayr, it could only be the Almohads, his masters whom he considers to be the most qualified to support the right and truth, while he sees the East stained by dissenting sects and heterodox currents.

Conclusion

The rihla was important in medieval Islam because it brought Muslims closer to knowledge: the core of their faith, culture, and civilization. Looking at the rihla from this perspective allows us to understand the process and perspective of these scholars in a different way.

It became the necessary means by which medieval scholars researched and studied with recognized authorities. Subsequently, the rihla also became a means of disseminating knowledge. Classical Islam’s commitment to the “direct”, face-to-face transmission of knowledge required the movement of people. It is in this context that we can understand the importance of the rihla for Islamic sciences.

You can follow Professor Mohamed Chtatou on Twitter: @Ayurinu

Bibliography

Bonebakker, S. A. “Three manuscripts of Ibn Jubayr’s Riḥla, “Rivista degli Studi Orientali, 1972, pp. 235-245.

Broadhurst, R.J.C. (traduction). The Travels of Ibn Jubayr. London: Jonathan Cape, 1952, p. 15 (“Introduction”). For the text in Arabic see: Ibn Jubayr, Rihla. Beirut: Dar Sadir, 1964.

Calasso, Giovanna. ‘’Les tâches du voyageur : décrire, mesurer, compter, chez Ibn Jubayr, Nāser-e Khosrow et Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, ‘’ Rivista degli studi orientali, 73/1, 1999, pp. 69-104.

Charles-Dominique, Paule (Edition and translation). Voyageurs arabes. Paris : Gallimard, 1995.

Chtatou, Mohamed. ‘’L’importance littéraire et culturelle de la « rihla »,’’ Article.19-ma du 7 novembre 2021. https://article19.ma/accueil/archives/147594

Dejugnat, Yann. ‘’Voyage au centre du monde. Logiques narratives et cohérence du projet dans la Rihla d’Ibn Jubayr, ‘’ in Bresc, H. et Tixier du Mesnil, E. (ed.), Géographes et voyageurs au Moyen Âge, Paris, 2010, pp. 163-206.

Ghouirgate, Abdellatif. ’’Saladin d’après Ibn Ğubayr ,’’ in Weber E., De Toulouse à Tripoli, itinéraires de cultures croisées. Toulouse : AMAM, 1997.

Grousset, René. L’histoire des croisades et du royaume franc de Jérusalem. (9 volumes). Paris: Editions Perrin, Tempus. 2006.

Ibn Jubayr. The Travels of Ibn Jubayr. Translated by R. J. C. Broadhurst. London: Cape, 1952.

Netton, I. Richard. “Basic structures and signs of alienation in the ‘Riḥla’ of Ibn Jubayr, “Journal of the Arabic Literature, 22/1, 1981, pp. 21-37.

Pellat, Charles. “Ibn Djubayr,” Vol. III: The Travels of Ibn Jubayr, Critical Concepts in Islamic Thought. London and New York: Routledge, 2008, p. 755.

Peters, F.E. The Hajj: The Muslim Pilgrimage to Mecca and the Holy Places. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1996.

Sauneron, Serge. ‘’Le temple d’Akhmim décrit par Ibn Jobair, ‘’ Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 51, 1951, pp. 123-135.

Starkey, Paul. “Ibn Jubayr al-Kinani, Muhammad Ibn Ahmad (AD 11451217)”, in Ian Richard Netton (ed.), Encyclopedia of Islamic Civilisation and Religion. London and New York: Routledge, 2008, p. 256.

Weber, El. “Construction of identity in twelfth-century Andalusia: the case of travel writing,” Journal of North African Studies, 5/2, 2000, pp. 1-8.

W. Wright (ed.). The travels of Ibn Jubair. Leyden: Brill, 1852, re-edited and revised by M. J. de Goeje, Leyden-London: Brill, 1907.