Articles

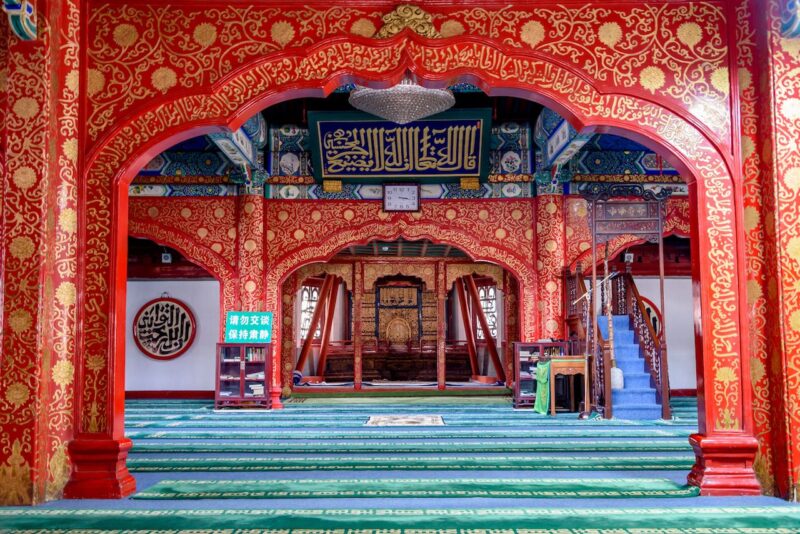

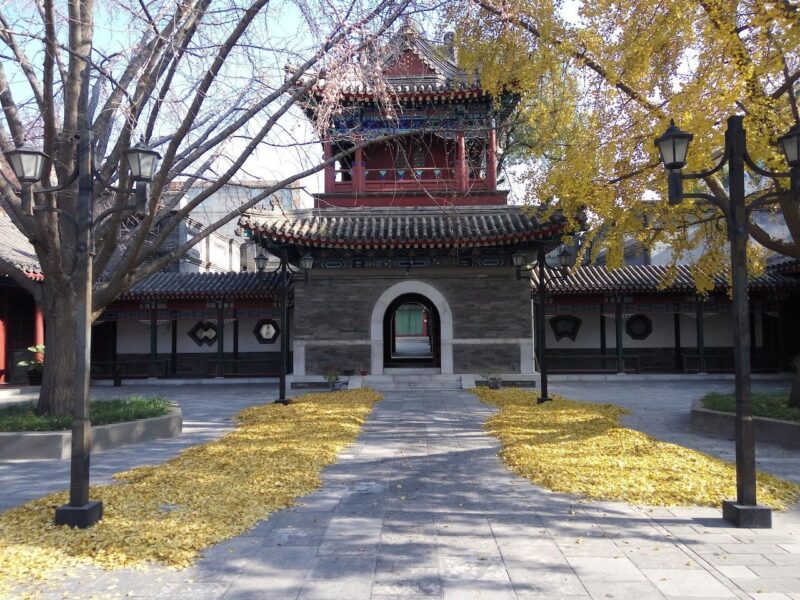

Astonishing mosques in China

Article author: Angelo Zina

Date of publication of the article: 27/10/2020

Year of publication: 2020

Article theme: Architecture, Art, History, Islam, Religions.

China has an ambiguous stance in regards to institutionalized faith. On the one hand, the People’s Republic recognizes five religions — Buddhism, Catholicism, Daoism, Islam, and Protestantism — and protects freedom of religious belief under its constitution, but on the other, the Council on Foreign Relations reports that “China is home to one of the largest populations of religious prisoners, likely numbering in the tens of thousands.”

With about 22 million believers, Muslims comprise less than two percent of China’s population, divided predominantly into 10 different ethnicities. The two largest Chinese Muslim groups are the Hui and the Uyghurs. While the former — mostly settled in the central part of the country in the Ningxia Autonomous Region and the Gansu, Qinghai, and Yunnan provinces — has managed to integrate well within Chinese society, the latter, a Turkic minority of 10 million people living in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region in the northwest, continues to suffer from severe repression and persecution.

With about 22 million believers, Muslims comprise less than two percent of China’s population, divided predominantly into 10 different ethnicities.

Last summer, the Hui made the news for protesting in the thousands against the announced demolition of the newly built Weizhou Grand Mosque; however, the Uyghurs have faced much more serious attacks over the past decades. Religious practice in Xinjiang is closely controlled by the Chinese authorities since militant Islamic separatist groups asking for the independence of East Turkestan have formed in the region, and the conflict between government forces and local activists has turned violent on various occasions. Xinjiang is said to be one of the most heavily policed areas in the world and reports of human rights abuses abound. In 2017, it was reported that 200 mosques had been destroyed in the area and 500 more were scheduled for demolition. It is also estimated by the United Nations that nearly three million Muslims have been detained in hidden “reeducation camps,” which are compared to “gulags” by the international press.

Last summer, the Hui made the news for protesting in the thousands against the announced demolition of the newly built Weizhou Grand Mosque

Within this strictly regulated society, Chinese Muslims continue, nevertheless, to express their cultural heritage in houses of worship. Here are seven of the most fascinating examples of mosques in China that are still standing.