Articles

Andalusia, mon amour, part 2

Article theme: Al-Andalus, History, Islam, Philosophy, Religions.

This is the second part of Dr. Chtatou’s text on Al-Andalus, its history and development. (Click here to read part 1)

Multiculturalism and tolerance in Andalusia: convivencia

The Muslims of al-Andalus tolerated the “People of the Book”: Jews and Christians could therefore freely practice their religion: go to religious schools, build churches and synagogues, celebrate their religious holidays. This tolerance lasted four centuries until the arrival of the Almohads.

Once upon a time there was a happy Andalusia, where Jewish, Christian and Muslim scholars peacefully quoted. Is it a model or a useless myth?

Andalusia… For the Syrian-Lebanese poet Adonis, this southern part of Spain would have been, in the Middle Ages, under the aegis of the Muslim dynasty of the Umayyads of Cordoba (756-1031), the place par excellence of a successful crossbreeding. There would have existed a Spain of three cultures where Muslim, Jewish and Christian monotheisms would have managed to coexist in good understanding, and even to maintain a fruitful collaboration. A model for our present…

It will not be difficult to find contrary opinions. Mainly, it is true, on “Islamophobic” sites, where the idea is developed, for example, that it is a myth, “that Islamophiles of all kinds come to us to demonstrate that Islam is a religion of peace, tolerance and freedom, and that the Andalusian period was a golden age of Islam and European civilization.”

In medieval Spain, Muslims, Jews and Christians were able to invent tolerance.[i] The Andalusian culture of this period is that of the mixtures, a prosperous society rich in splendor, where ideas and texts were exchanged and circulated in languages that were themselves mixed. With erudition and true writing, Maria Rosa Menocal[ii] retraces the history of Andalusia between the 8th and 15th centuries, based on “motifs” or remarkable figures: poets, troubadours or philosophers, intellectuals, men of science and politics and the “jewel of the world” with its palaces, libraries or gardens, mosques and synagogues.

The influence of this civilization and the relations it developed with Europe and the Mediterranean basin were halted by the rise of religious intolerance and the advent of the Black Death; in extreme violence, the autodafés (book burning) marked the destruction of the treasures of al-Andalus.

According to the almost unanimous chorus of historians, the convivencia, as a term and concept, is said to have been invented by the Spanish philologist Américo Castro, in his seminal 1948 work “España en su Historia, Cristianos, moros y judíos.“[iii] Thus, among many other examples, Brian Catlos in a recent article stated that “the idea of convivencia [was] proposed by Américo Castro, ” [iv] giving rise to the myth we are discussing here. In many ways, however, this is an error that is all too often repeated.

In Castro’s writings, finally, the convivencia is not constructed as a concept, it is only one word among others to designate the coexistence between the members of the three religions. He uses it in a much less systematic way than other terms that he sees as clearly synonymous, such as tolerance and, even more so, contextura:[v]

(“[…] I aspire to explain how the peculiarity of the great Hispanic values was formed. I can be wrong: but I want to run the risk of being wrong, and in spite of this I want to affirm that the originality and universality of the Hispanic genius has its origin in the forms of life woven by nine hundred years of Christian-Islamic-Judaic contexture.“)

In discussing of the concept of convivencia, Christophe Cailleaux[vi] writes:

“Moreover, Castro nowhere evokes perfectly harmonious relationships. In the first place because, as a philologist and literary historian, he is interested in literary and linguistic transfers and only places his reflection on the terrain of concrete, everyday relationships on the margins. Secondly, the convivencia, in his pen, is neither positive nor happy in itself; it also implies and encompasses oppositions, resistances, and rejections. Indeed, obsessed with the destiny of his country, Castro wondered about the causes of what he perceived as the “disease of Spain “. His answer is ambiguous and even contradictory. Certainly, in his eyes, this failure is due to the rejection of Jews and Muslims by Christians, thus wrenching from Spain by a kind of self-mutilation two of the three founding elements of its identity. But at the same time, he sees the fusion of Christian, Jewish and Muslim elements as the root of the Spanish malaise; he goes so far as to affirm that the Inquisition and even the obsession with the purity of blood are direct legacies of the “Jewish element. ” The convivencia thus appears to Castro as a source of pride, a ferment of the originality and grandeur of his country, but also as a fundamental handicap explaining his country’s contemporary backwardness in the concert of European nations. “

Before the conquest by the Muslims, the population of Spain was made up of Hispano-Roman Visigoths who were either Christians or Jews. They were of Latin culture, that is, they spoke Latin. With the conquest of Spain by the Muslims, Arabs and Amazighs/Berbers were added to this population.[vii]

The population of al-Andalus was therefore very varied:[viii]

The Arabs: they arrived in the 8th century and in the 12th century in the Almohad period. They played an important political role;

The Amazighs/Berbers: General Tarik Ibn Ziyyad who undertook the conquest of Spain in 711 was an Amazigh/Berber. The Amazighs/Berbers are a people from North Africa who inhabited this region before the arrival of the Arabs. Most of the Amazighs/Berbers worked in agriculture, animal husbandry or handicrafts;

The Mozarabs: these are the Christians of Spain who abandoned Latin to speak Arabic: and

The Muwallads: these are the Christians who converted to Islam. They had privileged positions.[ix]

The Jews: they were very happy with the arrival of the Muslims because the Visigoths mistreated them. They integrated perfectly into Arab-Muslim society until the Almohad invasion.

City development

The Arabs favored the development of large cities: Cordoba was in the Middle Ages the largest city in Europe. They greatly modernized the cities by installing a sewerage system and many public amenities such as street lighting. The Arabs developed culture and knowledge by building many libraries, universities, schools… In the city, the medina was the fortified core, composed of many streets and alleys. There were zocos (from the Arabic suk) or markets, public baths (hammam), mosques, inns and sometimes universities. In the districts, the populations were grouped by activity in guilds (the craftsmen: jewellers, potters, weavers…) or by religion. Thus, Juderia was the Jewish district and Mozarabia the Mozarabic district.

Around the medina were the suburbs, more modern districts, the cemetery was located outside the city. The military and their families lived in the Alcazaba (al-qasabah), an independent fortified citadel.

In the countryside, the lords owned large agricultural properties. The rulers also owned rich properties with beautiful gardens and fountains. But there were also farmers and herders who worked their own land. Agriculture was able to develop thanks to irrigation techniques brought by the Arabs.

Olive trees, cereals and vines had been cultivated in Spain for a long time. The Arabs brought the cultivation of rice, pomegranate, cotton, saffron, eggplant, artichoke, endive and asparagus.

Culture and Knowledge

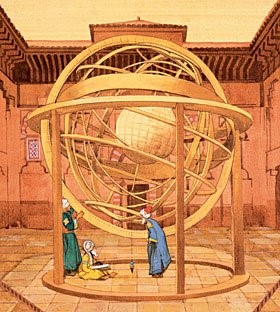

While in the rest of Europe wars were raging, Andalusian leaders were developing culture and knowledge. They supported scientists, philosophers, artists, poets… People came from all over the world to learn medicine, mathematics and poetry. Great scholars were born in Andalusia: Avempace, Averroes and Maimonides…

In Andalusia, medicine was more modern than in the rest of Europe. Surgery was practiced; medicines were invented and hospitals were built. Andalusian doctors wrote medical encyclopedias.

The Great Mosque of Córdoba, built between the end of the 8th and the end of the 10th century, illustrates the affirmation of the new power and the formation of a cultural identity. In the middle of the 9th century, the case of The Martyrs of Cordoba highlighted the crisis caused by the Arabization and Islamization of the Christians. A century later, the figure of Hasdai ibn Shaprut, the Jewish secretary of Abd ar-Rahman III, attests to the integration of the Jewish community of al-Andalus, and to the influence of the caliphate; He went on an embassy visit to the Byzantine emperor.

At the same time, the construction of the palace of Madinat az-Zahra’, destroyed by the Amazighs/Berbers during the unrest of 1009, was both a political manifesto and a cultural achievement in Andalusia. The Andalusia of the Taifas remained a fertile cultural breeding ground in the eleventh century: Samuel ibn Nagrila, the Jewish vizier of the king of Granada, first had the idea of composing poems in the sacred language, Hebrew. The Necklace of the Dove of Ibn Hazm[x] shows that Arab love poetry was at its peak. The Normans who conquered Barbastro in 1064 and appropriated the musicians of the Arab notables transmitted this poetic sensibility to the Latin world.

The Reconquista gave rise to several forms of acculturation, of which Toledo provides the best illustrations in the 12th century, with its monuments of Mozarabic art (including the Church of San Roman) and its school of translators. In the 13th century, the city was the first scientific center of the West. Emperor Frederick II, who was a great admirer of Arabic knowledge, employed intellectuals who had been trained there, such as Michel Scotus.

The inhabitants of the conquered Spain were considered scholars everywhere: the converted Jew Peter Alfonso taught Arabic and astronomy in London, and popularized the fable genre on the model of the Thousand and One Nights. At the same time, the Andalusian cultural tradition was in decline, as revealed by the brutal rejection of poetry in favor of theology by the intellectual Judah Halevi, and his departure for the East, caused by the crisis of the Jewish community under Almoravid rule.

The trip to Spain in 1142 by Peter the Venerable, the abbot of Cluny, with the aim of making a Latin translation of the Koran, constitutes a key moment in the importation into the West of this debate between faith and reason. The repeated condemnations of averroism – named after the Cordovan philosopher Ibn Rushd, who in the twelfth century attempted to reconcile the two forms of thought in his commentary on Aristotle – at the University of Paris in the thirteenth century testify to the ecclesiastical opposition to the Andalusian state of mind.

Hispania, which became al-Andalus, gave birth to an original culture, made up of crossed heritages between the Arab, Latin, Jewish and Greek worlds. A large part of the transfer of knowledge from the Muslim world to the Latin world was carried out thanks to the translation from Arabic from the 10th century onwards: Catalan convents had close contacts with Arabic knowledge; monks worked on translations of astronomy or arithmetic works. In the 12th century, the Toledo school was considered the first center for translating Arabic into Latin. Toledo is a center of multilingual culture with a large number of Arabic-speaking Jews and Christians. Jewish translators switch from oral Arabic to Spanish and Christian clerics transcribe Spanish into Latin. Books therefore hold an important place in the Arab-Muslim world: the cities of Toledo, Zaragoza, and Granada were home to imposing libraries with many copyists.

Al-Andalus is the result of interactions between the different Muslim, Jewish, Christian and Byzantine cultural areas. These various influences concern literature, art, science and technology. Astronomers, agronomists, doctors, botanists, philosophers, musicians and poets have contributed over the centuries to create the rich cultural range of al-Andalus. Among them are the physician Avenzoar, the jurist, theologian and philosopher Averroes, the geographer al-Idrisi, and the Jewish theologian Maimonides. Archaeological and historical research demonstrates the importance of this heritage in the development of Western civilization.

Andalusian scholars, or ulemas, who willingly combine the interpretation of sacred texts and legal customs with curiosity for astronomy, medicine or botany, have almost all traveled, to train – in Kairouan, Cairo or Baghdad – or to make the pilgrimage to Mecca, sometimes taking advantage of the opportunity to engage in trade. They constituted an influential body, active in administration, and promoted the contribution of knowledge and ideas developed elsewhere in the Muslim world.

The latter are particularly abundant in the first decades of the Abbasid Caliphate. Caliph al-Mamun, who reigned from 813 to 833, protected the Mutazilite movement,[xi] a rationalism that bordered on free thought. And he actively promoted the translation of Greek authors, often entrusted to Syriac Christians before being transcribed into Arabic. Although Mutazilism did not survive the subsequent political tensions, the study of the “science of the ancients”, philosophy, continued to develop in Baghdad, Samarra and Khorassan. Al-Farabi (872-950) attracted by his comments on Aristotle earned the undisputed qualification of “second master” (after the Greek philosopher), while a century later, Ibn Sina by his works, in medicine and philosophy, carved out a glory that would distinguish him even in Christianity under the name of Avicenna.[xii] These are just two of the scholars whose writings are still discussed greatly, today, throughout Dar-al-Islam.

Their ideas reached Al-Andalus, where they made their own translations, notably of Dioscorides’ “medical matter”, enriched on the basis of local botanical species. They also studied the Almagest of Ptolemy, which the Andalusian astronomer Al-Zarkali (Azarquiel)[xiii] completed and corrected. Applied sciences such as agronomy and medicine, initially in Christian hands, are also honored, as well as genealogy, fueled by the tendency of Amazighs/Berbers and Christians to invent Arab ancestries. Knowledge is disseminated, sometimes in rhyming form, in the adabs, treatises on the customs and knowledge indispensable to the honest man. Biographies of scholars are compiled to bear witness to the extent of Andalusian knowledge.

A jurist committed to fighting Malikite traditionalism, a fervent advocate of medicine, and a commentator on Aristotle, Ibn Rushd believes, like Ibn Tumart (and, in his own way, Maimonides), in a search for God through reason, which led him to attack the Persian mystic Al-Ghazali, who in the previous century had launched a violent attack on philosophy. Ibn Arabi, for his part, was in line with Al-Ghazali’s pursuit of an intuitive knowledge of God through asceticism and spiritual quest. Considered one of the principal mystics of the Muslim world, he knows a posterity without comparison with that of Averroes, whose influence exerted itself above all on the Christian world of the early Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Science flourishes

Al-Andalus was, in many ways, radically different from Christian Europe. While rural Europe had become impoverished, al-Andalus was a region of prosperous cities oriented toward trade. Its products, including glass, paper, leather, goldsmiths, and silks, enjoyed a high reputation as far away as India. Muslim rulers generally tolerated Christians and Jews and encouraged cultural diversity.

The contributions of Muslims enriched Spanish culture. Hispano-Muslim civilization participated in the golden age of Islam. Science, medicine and philosophy flourished, especially in the capital city of Cordoba. Spanish Islamic scholars, such as Averroes, studied the works of Aristotle and other Greek philosophers, which were translated into Latin before being spread throughout the rest of Europe. The caliphs built libraries and encouraged the blossoming of culture: the future Pope Sylvester II came to Barcelona to study the science of the Arab sages. A certain number of words in the Spanish language come from Arabic. New cultures and agricultural techniques, coming from Africa or the East, were introduced. The large cities of al-Andalus were centers of refined craftsmanship (leather work in Cordoba). They were also important markets and centers of study.[xiv]

Based on Greek, Persian and Indian knowledge, Arab medicine developed largely thanks to great figures (Ibn Sînâ, Ibn Rushd…) and discoveries resulting from a mastery of the theoretical aspects of this science and a keen sense of observation. The medicine of the time sought both to maintain good health (hygiene and dietetics) and to treat certain diseases; manuscripts and instruments testify to the practice of surgery. The practice of surgery was widely studied and compiled in a reference work written by the Andalusian physician Az-Zahrawi (11th century). Anatomy will also be approached with a new look at the human body. Medicine has largely developed thanks to the infrastructure of hospitals, both places of care and training. Research in the medical field was also devoted to the pulmonary circulation observed by Ibn an-Nafis.[xv]

Some prominent figures of al-Andalus

Abu al-Quasim az-Zahrawi (936-1013), known as Abulcasis to the Latin, a physician from Cordoba, known to be the founder of modern surgery, his treatise at-Tasrif [xvi]is a thirty-volume encyclopedia of medicine translated by Gerard of Cremona. It will be used for five hundred years by major medical universities such as Montpellier or Salerno. He is the inventor of the technique of cauterization, as well as several surgical instruments.

Ibn Rushd (1126-1198), known as Averroes, physician of the Caliph, jurist, philosopher, born in Cordoba in a family of recognized câdîs (jurists). He is famous in the Latin world for having renewed the analysis of Aristotle’s De Anima. One of his famous works is the Decisive Discourse in which he defends philosophy as an intellectual discipline compatible with faith in response to Al-Ghazâlî, author of several works on medicine, including the Colliget (Koulliyyât = generalities), inspired by Avicenna (Ibn Sina, 980-1037). Much of his research will be transmitted to the Latin world by Jewish translators of Arabic language.

Mûsa Ibn Maymûn (1138-1204), known as Moses Maimonides,[xvii] born in Cordoba, contemporary of Averroes, he is also a doctor and philosopher. He comes from a great lineage of Andalusian scholars. An Arabic-speaking, avid reader of Al-Farabi (a Syrian philosopher and commentator on Plato and Aristotle). He contributed, like Averroes, to the renewal of philosophical thought by appropriating the Aristotelian heritage. He is also known to have contributed to a renewal of the commentary of the Mishnah (a reference compilation of Jewish oral tradition).

Ziryab (782 (?)-857), musician, singer, music theorist. According to Ibn Hayyan, he came from Mosul (Iraq) after a visit to Kairouan. He became the most famous musician of al-Andalus by exercising his talents at the Umayyad court in Cordoba. Ziryab is a legendary figure in the Arab world.[xviii] Thanks to the Emir al-Hakam, his protector, he is said to have developed a school of music and imported a culture of Baghdadian refinement to southern Europe. Thanks to his fortune, he revolutionized the art of the table. He is considered to have introduced chess to Europe.

Al-Idrisi: born in Ceuta(?) around 1100, geographer, he studied in Cordoba.[xix] At the request of the Norman king of Sicily, Roger II, he elaborated a planisphere that he accompanied with a commentary with encyclopedic tendency. This text, accompanied by a set of maps, is called Roger’s Book. Heir to Ptolemy the Greek, at the crossroads of the Muslim, Christian and Byzantine worlds, al-Idrisi promoted a scientific and modern approach to geography.

Conclusion

The establishment of an Islamized territory in southern Europe extended over several centuries at the end of numerous processes of hybridization, acculturation, exchanges, and conflicts between the multiple components of the people of al-Andalus.

The will to spread a unified model of Islam by the elites had to adapt to the different local contexts. Intercultural exchange between Visigoth populations of Christian origin, a strong Jewish minority, Amazighs/Berbers from Africa, and Arabs from Syria, gave rise to original cultural and social productions. The Arabic language contributed to the creation of an Arab-Muslim “supra-identity” common to the inhabitants of al-Andalus.

This Arabizing cultural climate generated a diversity of cultures and social statuses: the Mozarabs, Arabized Christians, the Muladis (Muwalladun), Christians converted to Islam who obtained important positions in Muslim Spain, the Mudéjars, Muslims under Christian influence and the Slavs (Sâqalibas), servile or freed personnel of Christian and Islamic origin.

Al-Andalus is the result of interactions between different cultural areas, Muslim, Jewish, Christian, and Byzantine. The assimilation of these various influences through the Arabic language, have concerned both intangible goods such as language, literature, scientific texts, techniques or systems of thought, as well as material goods such as tools, raw materials, handicrafts, and gardens.

A large part of the transfer of knowledge from the Muslim world to the Latin world has been carried out through Arabic translation companies since medieval times, notably by the Toledo school and Jewish translators of Arabic language. Archaeological and historical research on al-Andalus has shown the importance of the Arab cultural heritage in the development of European civilization.[xx]

The traces of this heritage can be found both in French literature through the influence of the great poet of love Ibn Hazm of Cordoba on the art of the troubadours, and the imprint of Mudejar architecture in the works of the Catalan architect Antonio Gaudi.

The Islamic heritage bears witness to eight centuries of the history of Spain, which was itself the creator of an original art form and, in the 10th century, enjoyed an incomparable influence in the dissemination of knowledge, science and literature. It is in Spain, especially in Andalusia, that we find the most numerous and best preserved monuments of this period from the 8th to the 15th century. From language to art and literature, agricultural techniques, handicrafts, tapestries and fabrics, it is all the Muslim heritage that still permeates Andalusia.

The cultural boom, which culminated at the end of the 11th century, began among the Umayyads of Damascus, who were the first to build libraries. During the reign of the Umayyads began the translation of Greek, Persian, Syriac texts that were copied and brought back to Andalusia. The number of published works is quite important. The use of paper made things easier. It was in Cordoba, then the most populated city in Europe, that Abd ar-Rahman III promoted the arts and sciences.

Why has Muslim Andalusia, more than any other moment in European history, been elevated to the status of a unique symbolic moment of universal significance? The history of Andalusia is indeed at the heart of a debate with multiple accents. If we are indeed in the presence of a privileged place and moment between East and West, the meaning of the event changes according to the angle from which one places oneself.

Remembrance of a lost paradise, an essential intermediary of scientific and philosophical transmission, or a privileged moment of syncretism and “conviviality”, Andalusia is a “place of memory” that is constantly revisited to support modern acts and designs, to found an exemplary history.

NOTES

[i] Cf. Karabell, Zachary. Peace be upon you: the story of Muslim, Christian, and Jewish coexistence (1st ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 2007.

The story of conflict and confrontation between Islam and the West has become daily news, but throughout the ages Muslims, Christians, and Jews have shared more than enmity and war: there is also a rich and textured history of coexistence that has all but disappeared from our collective memory. In this timely and revealing book, Zachary Karabell traces the legacy of tolerance and cooperation from the advent of Islam to the present day.

In an extraordinary narrative spanning fourteen centuries, Karabell introduces us to the court of the caliphs in Baghdad, where scholars of various faiths engaged in spirited debate. He evokes the wonders of medieval Spain, where Jewish sages, Muslim philosophers, and Christian monks together deciphered the meaning of God and the universe. He offers a portrait of the Crusades that goes beyond the rivalry of Saladin and Richard the Lionheart, and shows how Christians and Muslims lived side by side. And he paints a vivid picture of religious autonomy in the Ottoman Empire.

As he explores the growing tensions of the modern era, Karabell traces the rise of Arab nationalism, the redrawing of the Middle East map in the wake of World War I, and the increased hostilities following the creation of the state of Israel. Through it all, he reminds us that dialogue and friendship have always punctuated times of war and discord. Today, while some Muslims, Christians, and Jews engage in confrontation, others—in Dubai, in Turkey, and around the globe—find common ground. Remembering the legacy of coexistence and recognizing its prevalence even today is a vital ingredient to a more stable, secure world.

[ii] María Rosa Menocal, op. cit.

[iii] Cf. Américo Castro, España en su historia. Cristianos, moros y judíos, Barcelone, Crítica, 1983 [1re édition, Buenos Aires, Losada, 1948].

[iv] Brian A. Catlos, “Contexto y conveniencia en la Corona de Aragón: propuesta de un modelo de interacción religiosa entre grupos etno-religiosos minoritarios y mayoritarios,” Revista d’Història Medieval, no. 12, 2001-2002, pp. 259-268. In the same vein, Kenneth Baxter Wolf states that “It was the Spanish philologist and literary historian Américo Castro (1885-1972) who first used the term convivencia“: see Kenneth Baxter Wolf, “Convivencia in Medieval Spain: A Brief History of an Idea,” Religion Compass, vol. 3, no. 1, 2009: 72.

[v] Cf. Américo Castro, La realidad histórica de España, Mexico, Porrúa, 1954 : 61.

[vi] Cf. Christophe Cailleaux. « Chrétiens, juifs et musulmans dans l’Espagne médiévale. La convivencia et autres mythes historiographiques », Cahiers de la Méditerranée [Online], 86 | 2013. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/cdlm/6878 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/cdlm.6878

[vii] Adams et al. “The Genetic Legacy of Religious Diversity and Intolerance: Paternal Lineages of Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula. “The American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 83, 2008: 725. https://www.cell.com/ajhg/fulltext/S0002-9297(08)00592-2

[viii] Cf. Ruiz, Ana. Medina Mayrit: The Origins of Madrid. New York, New York: Algora Publishing. 2012: 57.

[ix] Cf. Fernando Rodríguez Mediano. The Orient in Spain: Converted Muslims, the Forged Lead Books of Granada, and the Rise of Orientalism. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. 2013: 42.

[x] Cf. Ibn Hazam (994-1064). The Ring of the Dove. A Treatise on the Art and Practice of Arab Love. Translated by A.J. Arberry, Litt.D., F.B.A. London: Luzac & Company, Ltd. http://www.muslimphilosophy.com/hazm/dove/ringdove.html

Preface:

“I have tried to translate as faithfully as possible, given the difficulties posed by the task of rendering a Semitic into an Aryan idiom. I do not think that the prose parts of this version need too much apology; but something ought certainly to be said on behalf of the pieces in metre and rhyme. The first thing to repeat and this is quite honestly not a case of an indifferent workman blaming his tools-is that Ibn Hazm was not a great poet; and as every translator is aware, there is no more baffling labour than to endeavor to do justice to the mediocre; the result is bound to be mediocre at best, and at worst it may be intolerable. If the translator possesses a sufficient degree of technical dexterity in versifying, he usually finds that indifferent verse is easier to stomach -when put into metre and rhyme than when dissected into strips of prose. And since his original for his part said what he had to say in rhyme and metre, it seems, at least to my way of thinking, that the interpreter should take the same trouble, for there is always the off-chance that he may occasionally produce something memorable. Those modern critics who decry the tradition, established in our own literature over several centuries, of rendering classical poetry into the traditional forms of English verse, have yet to prove, so far at least as Arabic is concerned, that their alternative solution of the problem is either theoretically more sound, or in practice, more successful. “

The passions most men boast them of

Are like a desert’s noontide haze:

I love thee with a constant love

Unwithering through all my days.

This fondness I profess for thee

Is pure, and in my heart I bear

True love’s inscription plain to see,

And all its tale is written there.

Had any passion, thine beside,

At any time my soul possessed,

I would have torn my worthless hide

And plucked that alien from my breast.

There is no other prize I seek:

Thy love is my desire sincere:

Only upon this theme I speak

To capture thy complacent ear.

This if I win, the earth’s expanse,

And all mankind, are but as dust,

Yea, the wide world’s inhabitants

Are flies that crawl upon its crust.

[xi] The Mutazilite thinkers are most often defined as rationalist, individualist, liberal and eccentric figures. To the above qualities, one should add ascetic and devotional aspects. Among the Mutazilite famous ascetics are Abū Mūsā al‐Murdar and his followers, Ja‘far b. Harb, Ja‘far b. Mubashshir and ‘?sā b. al‐Haytham. The accounts about these figures vigorously reflect the Mutazilite outlook of the ascetic life and practices. As a matter of fact, one can see the ascetic propensities in all the sects and schools of the early Islamic period. In view of their emphasis upon the love for God, they placed piety and austerity at the center of the relationship between the servant and God. In this context, this article attempts to provide insights into the pietistic dimension of the Mutazilite tradition.

Cf. Ess, Josef van. The Flowering of Muslim Theology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006.

“The Muʼtazilis are of theologians who argued for the importance of reason in religion and theology. Historiographers usually consider the founder of this group to be Wasil Ibn ʻAtaʼ (d. 748), who was a member of the Qadarite group led by al-Hasan al-Basri (d. c. 728). With the rise of the Abbasid dynasty, Muʼtazila became an important school of thought and soon divided into two distinct schools: the Basran school under the leadership of Abu al-Hudhayl al-ʻAllaf (d. 841) and the Baghdadi Muʼtazilite school under the leadership of Bishr b. al-Muʻtamir (d. 825). The two schools had different stances on a number of theological issues, noticeably in their adoption of the Greek atomism theory. According to ʻAbd al-Jabbar, atoms are the smallest constituent components of all bodies. Muʼtazilites also differed in their use of the al-aslah concept, which means that God does what is the best (al-aslah) for every human. At the end of the 10th century the Buhashimiyya school, under the leadership of Abu ʻAbdallah al-Basri and his student al-Qadi ʻAbd al-Jabbar, emerged from the Basran school as a result of the conflict around Abu Hashim’s theory of ahwal (modes). (This was part of an ongoing debate about the ontological status of the divine attributes.) The Muʼtazilites arranged their theological discussion first under their famous five principles (attributed to the 10th–11th century Basran scholar ʻAbd al-Jabbar” divine unity, divine justice, the promise of reward and threat of punishment, the “intermediate [nonjudgmental] position” regarding grave sinners, and the importance of commanding good and prohibiting evil). They dabbled in many other fields, such as cosmology, theodicy, ethics, and refutations of other sects and religions, and in their discussion of Imamates they also touched upon political issues. This can be seen in the encyclopedic work of ʻAbd al-Jabbar al-Mughni. This twenty-volume work was discovered in the 1950s and was published in Egypt between 1960 and 1969, sparking renewed interest in the Muʼtazilis. It is considered the most important surviving work of the Muʼtazila. See also the separate article on theology.“ https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780195390155/obo-9780195390155-0138.xml

[xii] Cf. Langhade et Mallet. “Droit et philosophie au XIIe siècle sous Al Andalus. “ Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée, no 40, 1985 : 104. https://www.persee.fr/doc/remmm_0035-1474_1985_num_40_1_2097

[xiii] Abū Isḥāq Ibrāhīm ibn Yaḥyā al-Naqqāsh al-Zarqālī al-Tujibi[1] (Arabic: إبراهيم بن يحيى الزرقالي); also known as Al-Zarkali or Ibn Zarqala (1029–1087), was an Arab Muslim instrument maker, astrologer, and the most important astronomer from the western part of the Islamic world. Although his name is conventionally given as al-Zarqālī, it is probable that the correct form was al-Zarqālluh. In Latin he was referred to as Arzachel or Arsechieles, a modified form of Arzachel, meaning ‘the engraver’. He lived in Toledo, Al-Andalus before moving to Córdoba later in his life. His works inspired a generation of Islamic astronomers in Al-Andalus, and later, after being translated, were very influential in Europe. His invention of the Saphaea (a perfected astrolabe) proved very popular and was widely used by navigators until the 16th century. The crater Arzachel on the Moon is named after him.

Cf. http://antropicos.blogspot.com/2012/04/azarquiel-el-gran-astronomo-de-al.html

[xiv] Cf. Pormann, Peter E. Medieval Islamic medicine. Savage-Smith, Emilie. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. 2007: 117.

[xv] Ala-al-din abu Al-Hassan Ali ibn Abi-Hazm al-Qarshi al-Dimashqi (علاء الدين أبو الحسن عليّ عليّ القرشي الدمشقي), better known as Ibn Al Nafis (ابن النفيس), born near Damascus around 1210 and died in Cairo in 1288, was an Arab physician and theologian who practiced and taught in hospitals in Damascus and Cairo in the 13th century. He is known to have been the first to describe the small blood circulation or pulmonary circulation in Cairo in 1242. He wrote a huge medical compilation, an encyclopedia planned in 300 volumes, but unfinished at 80 volumes due to his death. Only three of these have reached us: the manuscript is available in Damascus.

His other medical works are a book on ophthalmology, a commentary on Questions on Medicine for the Students of Hunayn ibn Ishaq, an abridged version of Avicenna Mujaz al-Qanun, and Kitab al-Mukhtar fi al-Aghdhiya, on the effects of diet on health, and numerous ‘commentaries’ on books by Hippocrates.

Cf. Ibn al-Nafis (translation of M. Meyerhof), The Theologus Autodidactus of Ibn al-Nafis. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968.

[xvi] Az-Zahrawi’s thirty-volume medical encyclopedia, Kitab at-Tasrif, completed in the year 1000, covered a broad range of medical topics, including on surgery, medicine, orthopaedics, ophthalmology, pharmacology, nutrition, dentistry, childbirth, and pathology. The first volume in the encyclopedia is concerned with general principles of medicine, the second with pathology, while much of the rest discuss topics regarding pharmacology and drugs. The last treatise and the most celebrated one is about surgery. Az-Zahrawi stated that he chose to discuss surgery in the last volume because surgery is the highest form of medicine, and one must not practice it until he becomes well-acquainted with all other branches of medicine.

The work contained data that had accumulated during a career that spanned almost 50 years of training, teaching and practice. In it he also wrote of the importance of a positive doctor-patient relationship and wrote affectionately of his students, whom he referred to as “my children”. He also emphasized the importance of treating patients irrespective of their social status. He encouraged the close observation of individual cases in order to make the most accurate diagnosis and the best possible treatment. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Al-Zahrawi.)

Cf. Arvide Cambra, Luisa Maria. Un tratado de polvos medicinales en Al-Zahrawi. Almeria: University of Almeria.1994.

[xvii] Cf. Davidson, Herbert A. Moses Maimonides: The Man and his Works. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2005.

[xviii] Cf. Glasser, Johnathan. The lost paradise: Andalusi music in urban North Africa. Chicago; London: The University of Chicago Press, 2016.

For more than a century, urban North Africans have sought to protect and revive Andalusi music, a prestigious Arabic-language performance tradition said to originate in the “lost paradise” of medieval Islamic Spain. Yet despite the Andalusi repertoire’s enshrinement as the national classical music of postcolonial North Africa, its devotees continue to describe it as being in danger of disappearance. In The Lost Paradise, Jonathan Glasser explores the close connection between the paradox of patrimony and the questions of embodiment, genealogy, secrecy, and social class that have long been central to Andalusi musical practice. Through a historical and ethnographic account of the Andalusi music of Algiers, Tlemcen, and their Algerian and Moroccan borderlands since the end of the nineteenth century, Glasser shows how anxiety about Andalusi music’s disappearance has emerged from within the practice itself and come to be central to its ethos. The result is a sophisticated examination of musical survival and transformation that is also a meditation on temporality, labor, colonialism and nationalism, and the relationship of the living to the dead.

[xix] Cf. Al-Idrisi. De Geographia Universali: Kitāb Nuzhat al-mushtāq fī dhikr al-amṣār wa-al-aqṭār wa-al-buldān wa-al-juzur wa-al-madā’ in wa-al-āfāq. Rome: Medici. 1592.

[xx] Cf. Perry, Marvin; Myrna Chase, Margaret C. Jacob, James R. Jacob, and Theodore Von Laue. Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics, and Society. Boston, Massachusetts: Cengage Learning. 2008: 261–262.