Articles

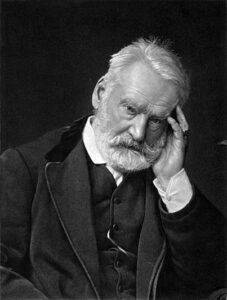

Victor Hugo and his poetry against Islamophobia

Article author: Tristan Semiond

Date of publication of the article: 08/02/2021

Year of publication: 2021

Even if Victor Hugo is internationally known for his literature, his poetry and his positions against absolutism, few people know that he was also committed to the defense of Islam, at a time when Islamophobia was already corroding the society.

Within his large repertoire, Victor Hugo has two poems dealing with Islam, “L’an IX de l’Hégire” and “Le Cèdre“.

His mystical period and his relation with God

“L’an IX de l’Hégire” is developed as a funeral eulogy of the prophet Muhammad. This text, which draws a portrait of the prophet in the last moments of his life, perfectly illustrates Victor Hugo’s knowledge of Islam – both of the Sunna, the Islamic tradition that narrates the sayings and actions of the Prophet, and of the Qur’an – as well as the respect he had for Muslim culture.

Il semblait avoir vu l’Éden, l’âge d’amour,

Les temps antérieurs, l’ère immémoriale.

Il avait le front haut, la joue impériale,

Le sourcil chauve, l’œil profond et diligent,

Le cou pareil au col d’une amphore d’argent,

L’air d’un Noé qui sait le secret du déluge.

Si des hommes venaient le consulter, ce juge

Laissant l’un affirmer, l’autre rire et nier,

Écoutait en silence et parlait le dernier.

Sa bouche était toujours en train d’une prière ;

Il mangeait peu, serrant sur son ventre une pierre ;

Il s’occupait lui-même à traire ses brebis ;

Il s’asseyait à terre et cousait ses habits.

“L’an IX de l’Hégire”, extract.

The French poet, Théophile Gautier, said of Victor Hugo that:

“To describe Muhammad, [Hugo] imbibes the Qur’an to such an extent that he could be taken for a son of Islam.”[1]

Similarly, the Académie Française member Alain Decaux, said during a speech for the bicentenary of Victor Hugo’s birth:

“The Bible no longer answers his questions. Why not discover the Qur’an? He finds an idea in the Qur’an that strikes him because it is his own: ‘Man is surrounded by God everywhere.”[2]

A contemporary poem to fight Islamophobia

Victor Hugo writes “L’an IX de l’Hégire” in his collection of poems La légende des siècles, just after the death of his love Léopoldine that drags him into a mystical crisis. This book traces the history of the world through some of the most important characters in history, such as Muhammad. In it, we find a second poem that speaks of Islam, “Le Cèdre“, but this time from a different point of view.

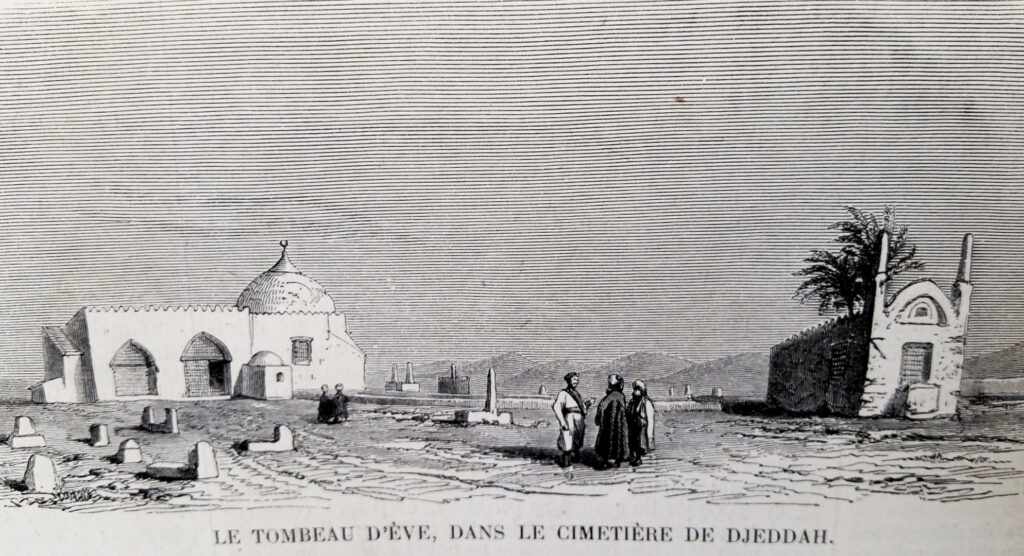

The poem “Le Cèdre” acts as a response to the Islamophobic discourses that proliferated in France and Europe following the assassination of the French and British consuls on June 15, 1858 in Jeddah (Saudi Arabia) during a massacre that took the lives of twenty-three people. The public opinion at the time blamed Muslims for this tragic event. In fact, in Europe, Islam was seen as a source of fanaticism and the source of motivation for these rebels, while the two colonial powers were increasing their domination and control over the region’s economy. However, some voices were already protesting against this Islamophobic discourse, and the great and renowned pen of Victor Hugo was one of them.

In his poem “Le Cèdre“, the poet treats Islam from a universal humanist perspective[3] with the aim of showing that opposing Islam to Christianity is against the laws of nature and history. To this end, the poem reproduces two mystical dialogues between St. John the Evangelist and the caliph Omar, and also between the city of Jeddah and Greece, which symbolizes here the cradle of European civilization. The city of Jeddah has a very important symbolic dimension for Victor Hugo, as well as for History, as it was in that city that the tomb of Eve was located according to mythology, before its destruction in 1928.

Omer, scheik de l’Islam et de la loi nouvelle

Que Mahomet ajoute à ce qu’Issa révèle,

Marchant, puis s’arrêtant, et sur son long bâton,

Par moments, comme un pâtre, appuyant son menton,

Errait près de Djeddah la sainte, sur la grève

De la mer Rouge, où Dieu luit comme au fond d’un rêve,

Dans le désert jadis noir de l’ombre des cieux,

Où Moïse voilé passait mystérieux.

Tout en marchant ainsi, plein d’une grave idée,

Par-dessus le désert, l’Égypte et la Judée,

À Pathmos, au penchant d’un mont, chauve sommet,

Il vit Jean qui, couché sur le sable, dormait.

Car saint Jean n’est pas mort, l’effrayant solitaire ;

Dieu le tient en réserve ; il reste sur la terre

Ainsi qu’Énoch le Juste, et, comme il est écrit,

Ainsi qu’Élie, afin de vaincre l’Antéchrist.

« Le Cèdre », extract.

Sadly, this issue continues to be relevant today, and Victor Hugo’s position with regards the Prophet Muhammad and Islam are very different from the one we can read and hear today in Western public opinion. Like any poem, it can be interpreted in different ways, but what is obvious after reading it is Victor Hugo’s humanist will to create symbolic bridges between Islam and Christianity, between East and West.

His admiration for the Emir Abd el-Qader and his silences on colonization

The author of Les Miserables is part of that group of writers who do not remain confined to literature and who have always actively participated in the political and social debate, both as writers, through their rhymes and metaphors, and as politicians, using their eloquence and oratory for the common good.

Paradoxically, Victor Hugo, who wrote about Islamic culture and the history of the Muslim world through his famous book Les Orientales, did not dedicate any of his works or political speeches (he was a senator between 1876 and 1885) to the colonization of Algeria, launched by his sworn enemy Napoleon III.

In spite of this, the Emir Abd el-Qader, a historical and symbolic character of the Algerian resistance against the French invasion, is the central protagonist of his poem Orientale. The name of this Emir continues to resonate in the world for his great deeds during the fight against the French invasion, but also for his kindness and his intelligence. He also holds a very important place in French literature, for example Arthur Rimbaud’ poem, Jugurtha.

The poem Orientale shows a complex representation of Abd el-Qader. Victor Hugo describes him as a “noble” and “monstrous” character, while also qualifying him of being a “thoughtful, fierce and gentle Emir”. This description is contrasted with that of a “man with a treacherous look”, who is none other than Napoleon III. The latter is also represented by a wolf “hated by mothers and women”, while the Emir is described as a “lion”, a “tiger”, a “hadji” or an “handsome soldier”. The lion Abd el-Qader seems to be considered by the author as a person of honor who fights and resists against the wolf Napoleon III, but who does not hesitate to use violence when necessary.

Lorsque Abd-el-Kader dans sa geôle

Vit entrer l’homme aux yeux étroits

Que l’histoire appelle — ce drôle, —

Et Troplong — Napoléon trois ;

Qu’il vit venir, de sa croisée,

Suivi du troupeau qui le sert,

L’homme louche de l’Elysée, —

Lui, l’homme fauve du désert ;

Lui, le sultan né sous les palmes,

Le compagnon des lions roux,

Le hadji farouche aux yeux calmes,

L’émir pensif, féroce et doux ;

Lui, sombre et fatal personnage

Qui, spectre pâle au blanc burnous,

Bondissait, ivre de carnage,

Puis tombait dans l’ombre à genoux ;

Qui, de sa tente ouvrant les toiles,

Et priant au bord du chemin,

Tranquille, montrait aux étoiles

Ses mains teintes de sang humain ;

Qui donnait à boire aux épées,

Et qui, rêveur mystérieux,

Assis sur des têtes coupées,

Contemplait la beauté des cieux ;

Voyant ce regard fourbe et traître,

Ce front bas, de honte obscurci,

Lui, le beau soldat, le beau prêtre,

Il dit : « Quel est cet homme-ci ? »

Devant ce vil masque à moustaches,

Il hésita ; mais on lui dit :

« Regarde, émir, passer les haches !

Cet homme, c’est César bandit.

« Ecoute ces plaintes amères

Et cette clameur qui grandit.

Cet homme est maudit par les mères,

Par les femmes il est maudit ;

« Il les fait veuves, Il les navre

Il prit la France et la tua,

Il ronge à présent son cadavre. »

Alors le hadji salua.

Mais au fond toutes ses pensées

Méprisaient le sanglant gredin

Le tigre aux narines froncées

Flairait ce loup avec dédain.

Jersey, le 20 novembre.

However, there is no mention or opinion on the legitimacy of his actions, and if there is any, it is only reflected in his opposition to Louis Napoleon Bonaparte. On the one hand, this poem conveys a certain admiration for Abd el-Qader, but, on the other hand, the character of the Emir is also used as a fierce criticism of Napoleon III.

His relationship with the Emir, whom he never met in person, is not limited to this poem. Victor Hugo also refers to him in Les Miserables, in which he speaks of the French betrayal to Abd l-Qader after his imprisonment in 1948, despite the Algerian governor’s promise to let him go free if he surrendered. There are also some notes of the author speaking about Abd el-Qader that have been found subsequently.

In the end, we must not forget that Victor Hugo is an author of the 19th century, which was marked by romantic orientalism, and his knowledge of the “Orient” was in fact conceptual, as he never visited a country of the North of Africa or the Middle East. In fact, the criticisms against him are numerous, especially for his silences on colonialism and his contradictory thoughts. Contradictions which, according to the French author Frank Laurant, led him to justify what he called the “civilizing missions” of the Third Republic, while criticizing them as the result of colonialism, which was for him a monstrous and violent process that could be the beginning of a new barbarism[4]. And he was right…

Victor Hugo’s biography has been marked by his contradictions, from monarchist to republican, from defender of the need for the “civilizing mission of Europe” to the criticism of colonization as “dirty work, which is better left to others”, as he said in his text Rhine in 1842.

In conclusion, the most important thing to remember about this great author are the values he defended, such as tolerance, fraternity, respect and, above all, his openness to the world, to other cultures, and his struggle for the will to understand the “Other”. A sentence from a letter of 1860 to M. Heurtelou, editor-in-chief of a newspaper in Port-au-Prince (Haiti), summarizes and symbolizes this humanist dimension: “On earth there are neither blacks or whites, there are spirits; and you are one of them.”

[1] Rapport sur le progrès des lettres (1868), citado in Paul Berret, La Légende des siècles, Mellotée, 1945.

[2] Alain DECAUX, Victor Hugo et Dieu, discours prononcé à l’académie française le jeudi 28 février 2002

[3] Louis Blin, Un poème méconnu de Victor Hugo comme antidote à l’islamophobie, 16/12/2020, L’Orient XXI.

[4] Franck Laurent, Victor Hugo face à la conquête de l’Algérie, Paris, Maisonneuve & Larose, coll. « Victor Hugo et l’Orient », no 6, 2001.