Articles

Hormuz island’s dichotomy, geopolitical hotspot or multicultural bastion

Article author: Antoni Sastre Bel - FUNCI

Date of publication of the article: 16/01/2020

Year of publication: 2020

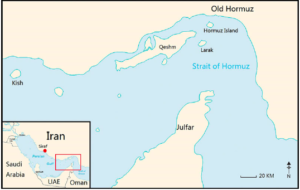

Today, when one thinks about Hormuz island and its representation in the international media, it is unavoidable to bear in mind the role it plays in the geopolitical board. Currently, 30% of the global oil consumed daily passes through the strait bearing the same name. Its status as a key passage in the global energetic shipping lines has prompted the surrounding states to advance their regional agendas through its control as main leverage, making the war drums sound an undesirable reality. Therefore, in case of confrontation between the opposed Gulf powers, Iran and Saudi Arabia, Hormuz would be the first place of encounter.

The rivalry among the mentioned states traces its origins to multiple historic and contemporaneous factors. In spite of this, the generalised media discourse attributes hostility to their divergent ethnic and religious natures. On the one side, Iran is regarded as the main regional Shia and Persian power, while, on the other side, Saudi Arabia is considered the undisputable Sunni and Arab leader. Thus, sectarian characterisation is used when explaining collisions between the two countries in any conflict, such as Iraq, Yemen or Syria. Following this logic, both powers are understood as homogenised units, in which there can be no other identity than the dominant one. In this article, we will attempt at illustrating how the Hormuz island challenges this alleged ethno-religious divisiveness feature.

Hormuz is a 42km2 island located in front of the Persian Gulf oriental shores, in the middle of the strait which inherited its name. Excluding its strategic location, there are two particularities which depict its singularity. The first one is its quirky rock formation, together with its layers of volcanic material, that reflects in more than 72 different colours that has prompted Hormuz to be known as the “rainbow island”. There are the peddling lunar-looking red, yellow or green mountains, dusted in salt and snaked by dry sulphurous bed rivers, raising among turquoise waters and silver-black sands. This is the main touristic attraction, but also a surprising spot for delighted geologists. The second one, refers to the population that dwells this bizarre island. It just takes five minutes to appreciate how, in the main city, Sunni mosques side the Shia ones, creating a singular atmosphere which is complemented by African rites carried out some special nights. Likewise, the language heard within its labyrinthine streets is not standard Farsi, but a dialect of it mixed with Somali, Baluchi and Arabic, called “Khaleeji”. In the same line, the racial origins of their inhabitants, are Arab instead of Persian, tweaked with African and Indian kinship. Therefore, the cultural fusion found in this peculiar space, slightly challenge the mentioned regional sectarianism. But, in order to understand the current cultural diversity reasons and its implications, we must look back at the splendorous but unknown island’s past.

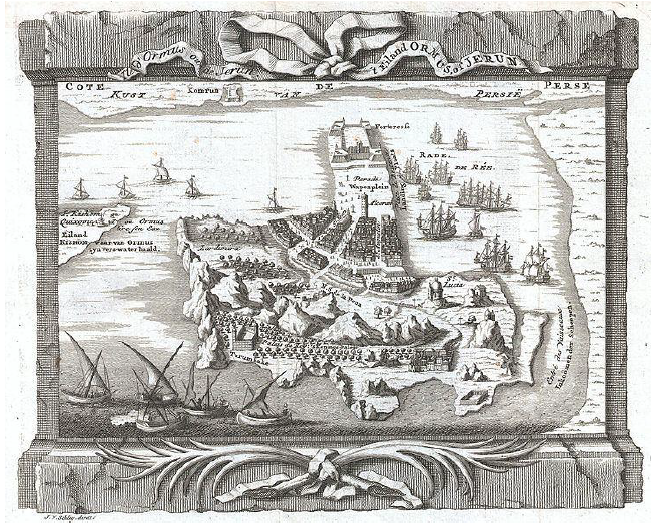

In its early days, both the islands and the current Iranian south, were territories occupied by the Arabic tribes called Hawala, originated in Oman. Those nomads settled on the shores and established harbours which would connect mainland Iran with the mainstream trade lines of the time. In this context, starting in the 11th century, the Hormuz Kingdom was consolidated around its capital (with the same name), which was located closer to today’s Minab. During that time, the coastal city achieved a steadfastness economic growth, consolidating as a relative regional power. In the forthcoming centuries, the Mongolian incursions, along with the inland empires’ decadence, allowed the Kingdom to expand its territories to the Omani shores, Gulf oriental islands and Bahrain, granting Hormuz partial naval hegemony. One of the most important references of those times was Marco Polo who visited the city twice (1272 and 1293). The wealth he witnessed was captured on his memories, written by Rustichello da Pisa. Finally, at the end of the 13th century and facing the imminent Mongol threat, Hormuz King Baha al-Din Ayaz decided to move the city to Jerun Island. Over time, this island would end inheriting the name of the exiled capital. From those mentioned centuries, it is important to outline how the daily commercial activity allowed the constant movement and mixture of Indians, Arabs, Persians and Africans, and with it, the benefits of trade overlapped the potential ethno-religious divisiveness.

In its early days, both the islands and the current Iranian south, were territories occupied by the Arabic tribes called Hawala, originated in Oman. Those nomads settled on the shores and established harbours which would connect mainland Iran with the mainstream trade lines of the time. In this context, starting in the 11th century, the Hormuz Kingdom was consolidated around its capital (with the same name), which was located closer to today’s Minab. During that time, the coastal city achieved a steadfastness economic growth, consolidating as a relative regional power. In the forthcoming centuries, the Mongolian incursions, along with the inland empires’ decadence, allowed the Kingdom to expand its territories to the Omani shores, Gulf oriental islands and Bahrain, granting Hormuz partial naval hegemony. One of the most important references of those times was Marco Polo who visited the city twice (1272 and 1293). The wealth he witnessed was captured on his memories, written by Rustichello da Pisa. Finally, at the end of the 13th century and facing the imminent Mongol threat, Hormuz King Baha al-Din Ayaz decided to move the city to Jerun Island. Over time, this island would end inheriting the name of the exiled capital. From those mentioned centuries, it is important to outline how the daily commercial activity allowed the constant movement and mixture of Indians, Arabs, Persians and Africans, and with it, the benefits of trade overlapped the potential ethno-religious divisiveness.

A key trade spot

The settlement of Hormuz in Jerun was a main turning point that reframed the commercial balance in the Persian Gulf, and consequently the trade routes between Middle East and South-East Asia. The strategic position of the Kingdom, together with its naval power, converted it in a mercantile transitory point and assured its control over the eastern part of the Gulf. That dominant status over the region, and their flexible customs policies towards free trade, allowed the transit of goods coming from multiple origins. Consequently, it gained the reputation of being “the vastest emporium of all the world”, as the Russian merchant Afanasy Nikitin would describe it. According to references provided by the Moroccan Explorer Ibn Batutta, the Kingdom controlled all of the trade going from India to Bagdad, circulating all types of products, from species to narcotics, including perfumes or metals. Furthermore, it also established contacts with Zanzibar or Abyssinia, from where wood and slaves were exported, or with China, whose route was set up by the renowned trader Zheng He, representing the Ming dynasty, in order to commercialise luxurious goods such as pearls, exotic animals or silk. Taking into account the fruitful economic activity, the Island population exponentially grew hosting approximately 50000 inhabitants at the early XVI century, according to the historian Jean Aubin.

An example of ethnic and religious tolerance

When looking back at how successfully the island economy performed, it seems clear that this couldn’t be achieved without the religious and ethnic tolerance standards they got. Instead of being reigned by Suni Muslims, the administration of the island allowed cultural free will, and didn’t meddle in the personal beliefs of its inhabitants. As described by historian Mohammed Vosoughi, the princes even came to participate in sacred ceremonies from different confessions, as a sign of respect. The hospitality, adaptability and inclusive capacity of the island reached such magnitudes that it was lauded by multiple western contemporary travellers and thinkers, such as the French Tomé Pires and Guillaume Thomas Raynal, or the Spanish Don Garcia de Silva y Figueroa. As the Jesuit Father Gaspar Barzeus once wrote:

“In Hormuz, God was celebrated four times a week. The Hindus on Monday, the Moors on Friday, the Jews on Saturday, and the Christians on Sunday.”

Therefore, even though the geostrategic location of the island played a huge role in its development, it must be recognised that the cultures’ myriad confluence wouldn’t have been possible without the readiness of a local administration to integrate the foreigner, without regarding their faith or origin.

In the early 16th century, the main European empires were seeking to dominate world trade routes and main strategic passages, for surpassing their opponents’ economic capabilities and gain geostrategic and military leverage. In this context, after centuries of unstoppable economic projection, in 1507, the Portuguese invaded the Hormuz, with the aim of strengthening the Estado do India and at dominating the spice commerce. Even though the invaders limited their occupation to imposing high taxes and defensive manoeuvres to defend from adversary powers, they ended up undermining the fiscal security bases of the Kingdom, and consequently diminishing development and assuring decadence. However, during this period, openness wasn’t eroded, and some Augustinians and Jesuits Christian missions were allowed to be settled in the Island. With them, in the same period, more than 800 Hindu households and several hundreds’ Sephardic Jews were embraced. Thus, Hormuz’s multicultural nature was reinforced, gaining an undisputed reputation. However, nothing lasts forever, and in 1622, Hormuz was occupied by Persian empire backed by the British, after which Shah Abbas moved the commercial harbour to the neighbouring Bandar Abbas.

This evidences that ethnical or cultural diversity does not need to be a bump in the road for coexistence.

Similarities with current times

By describing the Island’s past, our main aim was to gain an understanding of today’s quivering Hormuz diversity. Nevertheless, when comparing the magnanimous gone times with the unstable present, certain patterns might be discerned, which tell an unexpected reality. Although the former ethno-religious composition overshadows today’s diversity, stability and coexistence have been maintained for centuries. The mentioned factors might have been in the line of the French Liberal Economic Thinker Frédéric Bastiat’s statement: “If goods cross borders, soldiers won’t”. But at the same time, it must be recognised that even after 1622 decadence, cordiality has been maintained. Consequently, in daily social relations, singularities such as believing in the existence of 4 or 12 imams, or calling the Almighty “Allah” or “Khoda”, lose value when the neighbour main priority is peace, stability and prosperity. This evidences that ethnical or cultural diversity does not need to be a bump in the road for coexistence.

As a conclusion, we can notice how the main irruptions that have modified the natural behaviour of the island have been stemmed by exogenous factors. The Kingdom’s decadence was foretold in 1507, with the Portuguese occupation, and sentenced in 1622, when the British, pursuing the main world trade routes dominance, endorsed the invasion of the island by the Safavid Empire. Nowadays, in 2019, the less than 7000 Hormuz inhabitants, accuse north American warships of weakening their already decimated economy. Bearing in mind that ethnic-religious diversity doesn’t suppose a threat to social understanding, one might see how local cohabitation is closely tied and subjugated to geostrategic macro-policies set out by regional and international powers. In this light, and retracing ourselves to the beginning of this article, when thinking about Hormuz it should be born in mind not just the drones shot and the sabotage attacks, but the tolerance standards that one day caught worldwide attention. It is then when the words written by Alfoso de Alburquerque, after conquering the island five centuries ago, become meaningful:

“If the world is a ring, then Hormuz is its pearl”.

References

Melis, Nicola (Agosto 2016). The importance of Hormuz Luso-Ottoman Gulf-centred policies in the 16th century. Some observations based on contemporary sources. Università di Cagliari. Cagliari, Italia.

Vosoughi, Mohammed (2009). The Kings of Hormuz: From Beginning until the Arrival of the Portuguese. Proveniente de: Potter, Lawrence. The Persian Gulf in History. Palgrave. Nueva York, Estados Unidos.

Tazmini, Ghoncheh (2017). The Persian-Portugues Encounter in Hormuz: Orientalism reconsidered. Iranian Studies Journal. Oxford, Inglaterra.

Alonso, Carlos (1989). El primer viaje desde Persia a Roma del P.Vicente de S. Francisco, OCD. 1609-1611. Teresanium. Roma, Italia.

Córdoba, Joaquin (2005). Un caballero español en Isfahán. La embajada de Don García de Silva y Figueroa al sha Abbás el Grande (1614-1624). Revista Arbor. Madrid, España.

Mathee, Rudi (2015). The Mission of the Portuguese Augustinians to Persia and Beyond (1602-1747). Iranian Studies Journal. Oxford, Inglaterra.

Rubiés, Joan-Pau (2018). 1622 y la Crisis de Ormuz: ¿Decadencia o reorientación?. Universitat Pompeu Fabra. Barcelona, España.

Almeida, Graça (2015). El Consejo de Estado y la cuestión de Ormuz, 1620-1625: Políticas Transnacionales e impactos locales. Universidad de Évora. Évora, Portugal.

Meicun, Lin & Zhang, Ran (2015). Zheng He’s voyages to Hormuz: the archeological evidence. Peking University. Peking, China.

Ghasemilyeh, Bahar (2014). The effects of architecture on the tourism of Iranian Hormuz Island. Payam-e Noor University. Tehran, Iran.