Articles

Moriscos influence in Rabat and Salé in the 16th and 17th centuries

Article author: Aurora Ferrini Pernas

Date of publication of the article: 30/05/2023

Year of publication: 2023

Article theme: Archaeology, Architecture, Art, Craftwork, Culture, FUNCI, History, Immigration, Inmigration, Islamophobia, Marruecos, Morocco.

On 18 May, the Islamic Culture Foundation was invited to participate in the international conference entitled «Un mar de objetos, un mar de personas. Musulmanes y cristianos en el Mediterráneo de las edades media y moderna», con la ponencia «La influencia morisca en Rabat y Salé en los siglos XVI y XVII».

The Mediterranean has witnessed for centuries the movement of people, whether by land, sea, or air. The agents have been varied, as have their origin, religion, ethnicity, culture… Precisely, this conference has focused on presenting and discussing the results of a research that has devoted its efforts to studying these material manifestations and the impact of otherness on the collective imaginary through different religious contexts.

«Festival of Andalusi Heritage of Rabat and Salé». The starting point

Previously, in October 2022, the Foundation of Islamic Culture (FUNCI) inaugurated the «Festival of Andalusi Heritage of Rabat and Salé». This festival was born out of the need to reclaim and share the historical and cultural legacy that has united the two shores of the Bouregreg River, as well as the Mediterranean, for centuries.

Moroccans and Andalusí Almoravids, Almohads, and Marinids were part of the same universe and shared and exchanged their cultural traits. Later came the Moriscos expelled from Spain, who embodied the mixture of the two shores of the Mediterranean. This heritage has left an undeniable trace in all the cultural expressions of the two cities bordering the Bouregreg estuary: Rabat and Salé.

During the symposium held at the Cervantes Institute in Rabat, specialists in the Andalusi and Moriscos domains presented their research and highlighted the importance of continuing research in this field. As a foundation dedicated to the study and enhancement of the Islamic heritage in the Mediterranean, it was agreed that the intervention at the congress “Un mar de objetos, un mar de personas. Musulmanes y cristianos en el Mediterráneo de las edades media y moderna», con la ponencia «La influencia morisca en Rabat y Salé en los siglos XVI y XVII» would share the conclusions of the symposium organised in Rabat. The following article brings together the main points of some of the papers from this event, which guide the discourse and are adapted to the framework of the conference.

The flight to Morocco and the Moriscos question in Rabat-Salé

The first panel of the colloquium began with «Quelques réflexions sur un héritage en partage : l’héritage andalou au Maroc, d’hier à aujourd’hui», by the Moroccan historian Leila Maziane (2022). A starting point for the contextualisation of the Moriscos question in Rabat and Salé.

She began by reminding us that the 16th and 17th centuries were marked by the settlement in the Maghreb of a large contingent of migrants from the Iberian Peninsula, who numbered in the thousands. They began to arrive on the banks of the Bouregreg River in the 12th century, but it was not until the 17th century that the northern end of the estuary became a refuge for these families.

The best known stage is the one that began in 1610, with the establishment in Salé of settlers from Hornachos, a town in Extremadura. «Their arrival coincided with the Spanish occupation of the port of Larache in 1610 and the capture of La Mamora in 1614, which added value to the centre of Rabat-Salé, the only Moroccan port on the northern Atlantic coast» (García Arenal, 2013). The Bouregreg estuary thus became an important corsair hub.

A melting pot of cultures: the Moriscos as a vehicle for an inherited heritage

In the 11th century, with the arrival of Almoravid power, we witnessed a great opening up of the western Maghreb to Andalusi influences. The Almoravids were the first to introduce Andalusi architectural art. But it was not until the arrival of the Almohads that a symbiotic Moroccan-Andalusi art emerged. The Almohads were succeeded by the Marinids. This was the heyday of Andalusi art in Morocco. These relations did not end there. The arrival of the «andalusis», or Moriscos in the 17th century, served to reinforce the flow, and new trends reached the area.

«The quality and originality of the Andalusi heritage made Rabat and Salé one of the major keys to understanding the inestimable and still living heritage. But the most important heritage preserved from the time of al-Andalus is surely the human heritage» (Lakhdar, 2010).

As the writer Virginia Luque rightly expresses in her book El legado de al-Ándalus. La herencia andalusí y morisca en el Magreb (2017):

The Andalusi and Moriscos left a Rabat that rose from its ruins by extending and fortifying its walls, bequeathing a toponymy that gives names to streets, gates and mosques in the medina».

The port of Salé, an economic and cultural driving force

Although the Moriscos exodus of the 17th century made the name of Salé famous throughout the world, the era of splendour was reached with the Marinid dynasty. Salé then became the main port of the Kingdom of Fez and the most important commercial warehouse on the west coast; it was frequented by traders from all over the Christian world. Here merchants sold leather, wool, textiles, tapestries, ivory, wax, and honey, and bought cloth and manufactured goods from the Pisans, Catalans, Genoese, and Venetians.

In Rabat and Salé, on the other hand, the Moriscos introduced and developed a thriving agriculture and livestock industry, establishing irrigation systems using waterwheels, as well as their craftsmanship. These cities were also a vehicle for certain Spanish Renaissance styles, as well as embroidery motifs.

Midway between the 16th and 17th centuries

Before the establishment of the famous hornacheros in the Rabat-Salé area, there were other Moriscos living in the same area. What the historian Mercedes García Arenal wanted to refer to, in her speech «Moriscos en Marruecos polemistas contra el Cristianismo (2022)», is that there were cultivated people who played important roles such as doctors or translators, who contributed to the atmosphere of the Court of Marrakech and had an important production.

One of these cases is that of Ahmad b. Qasim al-Ḥaŷarī, also known as «Diego Bejarano». Some researchers suggest that he may have been born, around 1570, in the town of Hornachos (Villaverde Amieva, 2023; García Arenal, 2022). His fame is mainly because he is the author of a very important work called The Supporter of Religion against the Infidels. In it, he recounts a journey he made through Europe, mainly to France and Holland, with the task of recovering goods stolen during the expulsions of the Moriscos in the Iberian Peninsula. The trip also had the purpose of organising departures for these Moriscos and helping them to take refuge in various Muslim countries. From 1608 al-Ḥaŷarī moved to Salé where a large number of Moriscos were already settled.

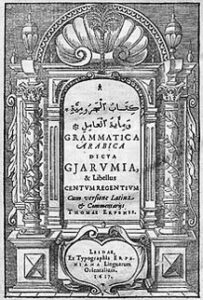

However, al-Ḥaŷarī was also influential in Holland through his personal contacts with the Dutchman Thomas Erpenius, the first professor of Arabic in Leiden whom he helped in the task of writing the first Arabic grammar in Europe, Grammatica Arabica. This shows the interesting intellectual influence and the dissemination of knowledge and documents that some of these Moriscos, working from Morocco, achieved in Holland and England. García Arenal (2022) believes that this information gives us a surprising and complementary view, which she finds very interesting, of what the Moriscos exile in Morocco was like.

This information gives us a surprising and complementary view, which she finds very interesting, of what the Moriscos exile in Morocco was like.

Some representative cases of the Moriscos imprint on material culture

In the Kasbah of the Udayas we can visit a recently renovated museum, housed in the main pavilion that Mulay Ismaïl had built at the end of the 17th century. In January 2023, the museum was reopened as the Musée national de la parure. Its collection includes objects related to personal adornments, such as Amazigh or Andalusi jewellery and Moroccan kaftans.

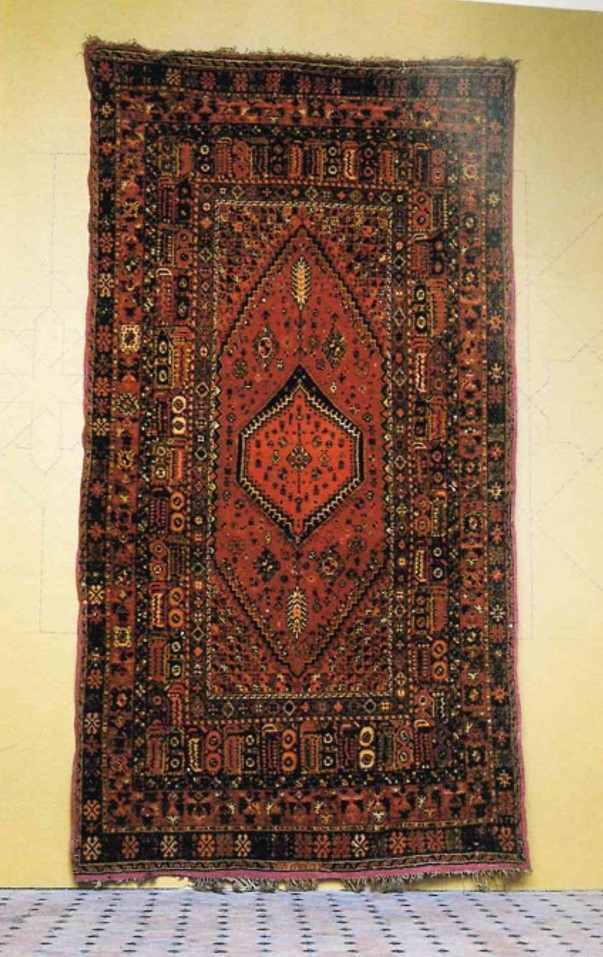

Another very representative example of the Moriscos passage through the area is the rbati carpet. Considered to be one of the most sumptuous woollen carpets in Morocco, the oldest carpets in Rabat date from the 17th century. According to Kamal Lakhdar (2010), it is probably a craft technique introduced in Rabat at the time of the Salé corsairs.

The carpet, which has a smooth pile and a fine texture, is made on fixed vertical looms, allowing several people to work in front of the work. Strict regulations require a minimum of 50,000 stitches per square metre, which can be as many as 160,000. The designs are quantitatively limited, and are based on the layout of a traditional Moroccan house with its courtyard, central water fountain, corridors, etc., both symbolically and schematically. Some have compared it to the appearance of a mihrab. A rosette is usually placed in the centre, on a red background. In addition, some evocative words may be woven into it.

Virginia Luque Gallegos (2017), in her book, reports another of these cases. During the feast of the birth of the prophet (Mawlid) in Salé, there is a well-known candlelight procession that dates back to the 16th century and is apparently of Ottoman origin. These elaborate banners take weeks to make. Until the early 20th century, the decoration of the candles was inherited and commissioned from a family of Andalusi origin. Salé is the only Moroccan city that celebrates Mawlid in this way.

Virginia Luque Gallegos (2017), in her book, reports another of these cases. During the feast of the birth of the prophet (Mawlid) in Salé, there is a well-known candlelight procession that dates back to the 16th century and is apparently of Ottoman origin. These elaborate banners take weeks to make. Until the early 20th century, the decoration of the candles was inherited and commissioned from a family of Andalusi origin. Salé is the only Moroccan city that celebrates Mawlid in this way.

Luque Gallegos (2017) also mentions Moroccan kaftans, although it seems that they are of Persian origin, «the Andalusi contribution is unquestionable. However, he mentions the Andalusi imprint in the embroidery of some of them. «Certain Nasrid and Moriscos influences can also be detected in the embroidery of bridal dresses and kaftans from Tetouan, Salé-Rabat, and Chefchaouen». The embroidery from Chefchaouen still reminds us of the embroidery from Granada with its geometric motifs.

«Certain Nasrid and Moriscos influences can also be detected in the embroidery of bridal dresses and kaftans from Tetouan, Salé-Rabat, and Chefchaouen.»

The arrival of the Moriscos in Rabat: the transformation of the city

Some remnants of the Moriscos legacy can still be seen in the kasbah today. If we were to go down Jama’ Street today, we would come to the platform overlooking the mouth of the Bouregreg, which houses a 17th-century lighthouse and an 18th-century warehouse, while if we were to go down Laalami Street, we would end up in a dead end at the Tour de Corsaires, also known as the «Tower of the Pilots»; this borj, or fortified bastion with a rough and massive appearance, dates from the 18th century.

In the dwellings of the Kasbah of the Udayas there are several doorways carved in Salé’s stone whose aesthetics are reminiscent of Spanish Plateresque and which the researcher Hafid Mokadem (2003) considers to be moriscas, doors that are still reproduced today.

A second group of Moriscos, faced with a possible attack, hastened to build a wall to protect themselves from external and internal enemies. This enclosure, which is partly preserved, is known as the «Andalusi wall»; today it would correspond to the area of the medina. The wall was flanked by 26 gates and a round bastion called Borj Sidi Makhlouf.

We can also visit the Moulina Mosque, located between Hassan II Boulevard and al-Mansour al-Dhahbi Street, which bears the name of an old Moriscos family from Rabat: Molina. This shows the continued importance of Moriscos families after the end of the Republic of Salé.

A particular element

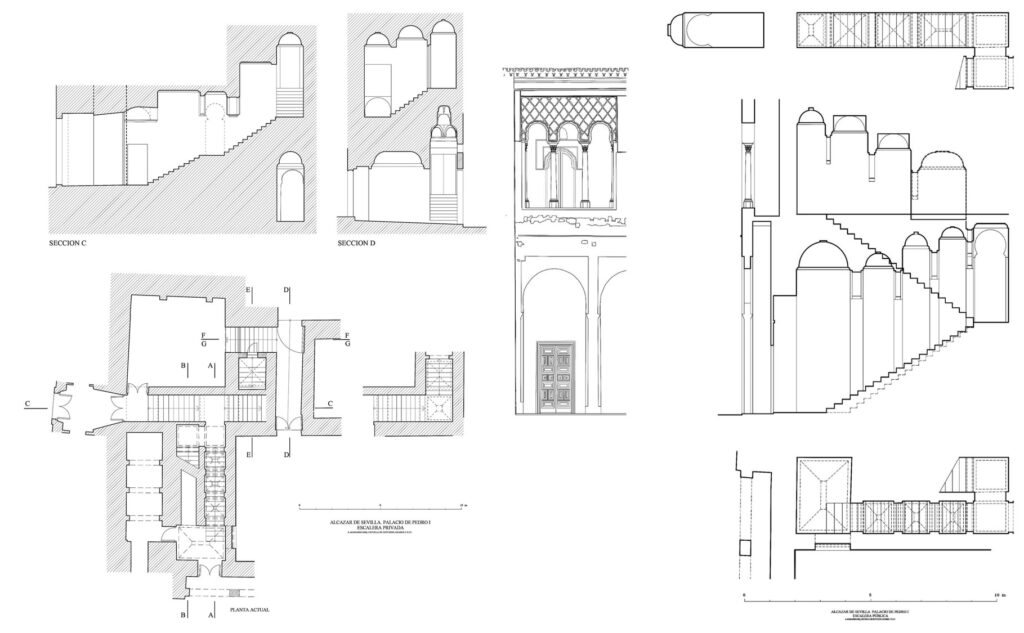

Antonio Almagro, architect and member of the Academia Real de las Artes de San Fernando (Madrid), enlightened us with his paper «Rabat and al-Ándalus. Arquitecturas de almohades y moriscos» (2022), on a very special case which, once again, connects both sides of the strait. His speech is reproduced in the following paragraphs.

It referred to the presence of a room, located on an upper floor, above the entrance hall or vestibule of the house, which:

The owner of the mansion uses these rooms to receive people from outside the family without these visits altering the life and privacy of the house. For this purpose, these rooms have direct access from the entrance hall via a staircase, separate from the one that connects the interior floors of the house. This arrangement has been observed in at least three main houses: Dar Karrakchu, Dar Lamrini and Dar Bargach.

FUNCI, during the celebration of the Festival, was able to visit the first of them, which belongs to an important family of Moriscos origin: The Carrasco family.

Reception rooms above the gates were common in the so-called castles, or rather “desert palaces” that the Umayyad dynasty built in Syria and Palestine […] This precedent is in any case difficult to relate to the cases of Rabat, both geographically and chronologically, which would be between the 8th and 17th centuries.

Some researchers have suggested that similar cases existed in al-Andalus, but so far there is no certain evidence of this. There is, however, a clear case of a similar layout that is in perfect condition […] This is the palace built by Pedro I of Castile in the Alcázar of Seville. This palace, of indisputable Andalusi roots, has a reception room on the upper floor, just above the vestibule and the chamber that the king had on the ground floor.

But the most interesting thing about this room is that there are two different staircases to access it. One starts in the hall of the palace, before passing through the door that marks the beginning of the private sphere of the king and his family, and the other, almost in contact with the first, starts in a small courtyard located within the private area of the monarch’s dwelling. In this way, the audiences in this room did not disturb the life and privacy of the king’s household.

This case, which is much closer, could have been a model for the buildings in Rabat. Although it is a subject that needs to be studied in greater detail, the Sevillian model may have influenced the solution adopted by some leading Moriscos families.

Research and the future: an undeniable heritage

This article sets out and expresses the need to pursue this line of research. Through this representative sample of the Moriscos legacy of the Rabat-Salé area, we wish to take a step towards the enhancement of a heritage that is impossible to analyse solely based on these two centuries, which has its origins in the past and undoubtedly marks the present.

The Moriscos were the guarantors of the transmission of the Andalusi legacy and contributed much other knowledge that shapes the identity of Spaniards and Moroccans and inexorably unites them. The Mediterranean and the Strait of Gibraltar are highly permeable spaces and the material culture is further proof of this reality, marked by Islamic civilisation and culture.

Aurora Ferrini Pernas – FUNCI

References

Almagro Gorbea, A. (2022, october 21). Rabat y al-Ándalus. Arquitecturas de almohades y moriscos [Colloquium]. Festival del Patrimonio Andalusí de Rabat y Salé, Rabat.

Almagro Gorbea, Antonio. (2023, mayo). Academia Colecciones. https://www.academiacolecciones.com/arquitectura/mostrar-autores.php?id=almagro-gorbea-antonio

García Arenal, Mercedes. (2022, october 21). Moriscos en Marruecos polemistas contra el Cristianismo. In Festival del Patrimonio Andalusí de Rabat y Salé [Colloquium]. Festival del Patrimonio Andalusí de Rabat y Salé, Rabat.

García-Arenal Mercedes. (2013). Los moriscos en Marruecos: de la emigración de los granadinos a los hornacheros de salé. In M. García Arenal and G. Wiegers, Los moriscos: expulsión y diáspora: una perspectiva internacional (pp. 275-311).

Luque Gallegos, V. (2017). El Legado de Al Ándalus: La Herencia Andalusí y Morisca en el Magreb. Almuzara.

Maziane, Leila. (2022, october 21). Quelques réflexions sur un héritage en partage : l’héritage andalou au Maroc, d’hier à aujourd’hui. [Colloquium]. Festival del Patrimonio Andalusí de Rabat y Salé, Rabat.

Mokadem, Hafid. (2003). La porte d’entrée de la maison maroco-andalouse de Rabat-Salé. In C. Gaultier-Kurhan, Le Patrimoine Culturel Marocain (pp. 223-265), Maisonneuve et Larose.

Monqid, S. (2009). Les morisques et l’édification de la ville de Rabat. Cahiers de la Méditerranée, 79, http://journals.openedition.org/cdlm/4939

Museum With No Frontiers. (2010). Le Maroc Andalou : À la découverte d’un art de vivre. Edisud.

Villaverde Amieva, J. C. (2023). Desde el exilio morisco: las glosas de al-Ḥaǧarī Bejarano al códice leidense del Kitāb al-Mustacīnī de Ibn Buklāriš. Mediterranea, 8, 89-192.