Articles

Women mystics of Islam, freedom and lordship

Article author: Inés Eléxpuru

Date of publication of the article: 23/09/2022

Year of publication: 2022

Article theme: Conferences, History, Islam, Religions, Women.

We reproduce the paper presented by Inés Eléxpuru, FUNCI’s Director of Communication, at the 6th ICLARS Congress held on 20 September. The communication took place in the panel on “Women’s spirituality and Islam”, which counted with the participation of Islamologist Asma Lamrabet and the theologian Juan José Tamayo. The panel was organised by the Euro-Arab Foundation for Higher Studies.

Any approach to the sources of Islam, especially the Qur’an and the Sira, or life of the Prophet Muhammad, shows that, from a spiritual approach, the equality between men and women is indisputable.

However, today I am going to refer in particular to the presence of women in Islamic mysticism. This presence is more relevant than in other branches of Islam, for, as Cherif Abderrahman Jah, the president of FUNCI, states:

“The ma`arifa, gnosis, or Knowledge with a capital letter, has no limits or boundaries, neither for men nor for women.”

For certain Muslim mystics, the feminine principle of Creation and the feminine figure as a source of contemplation of the divine are of great relevance, sometimes placing them before the masculine figure. For these mystics, masculinity and femininity are mere accidents and are not relevant to the essence of human nature.

For instance, the great 12th century mystic from Murcia (Al-Andalus, currently Spain), Ibn Arabi, said in his work The Links of Wisdom:

“Place yourself in any school of thought and you will find nothing but references to the feminine, even among those who affirm causality by saying that Allah is the cause of the existence of the World. Well: ‘the cause’ is feminine”.

It is interesting to note the importance attached in Islamic culture not only to the very rich and complex Arabic language, but also to the gender of words.

In this same work, Ibn Arabi reminds us of the Prophet Muhammad’s esteem for women, always form a spiritual perspective: “That is why he loved women: because of the fullness of the contemplation of the True One in them, for the True One is not seen naked of matter”.

On the other hand, the figure of the mother in Islam is of utmost importance and is charged with symbolism. Many words such as Umma (community), ummiyi (the term associated with the prophet), and many others, are derived from umm, mother. Qashani (d. 1329 A.D.), a disciple of Ibn Arabi, describes this question in his commentary on The Crimps of Wisdom in the following terms:

“The base or primeval origin of everything is called mother (umm), because the mother is the stem from which all branches spring (…) The origin of all origins, beyond which there is nothing, is called in the feminine haqiqa, or transcendent Reality (…), and the words referring to the divine Essence `ayn and dhat, are also feminine.”

As for the main attribute of Allah, which is Rahman (The Most Merciful), mentioned at the beginning of all suras, its trilithic root means womb, thus referring to God’s maternal and protective power towards His creatures.

A definition of Sufism

Before entering into the matter of female sanctity in Islam, it would be useful to define Muslim mysticism, also known as Sufism, or tasawuf in Arabic. Sufism is Islam in its deepest and most essential form. In this regard, I will begin by quoting María Tabuyo:

Before entering into the matter of female sanctity in Islam, it would be useful to define Muslim mysticism, also known as Sufism, or tasawuf in Arabic. Sufism is Islam in its deepest and most essential form. In this regard, I will begin by quoting María Tabuyo:

“The radicality of Islam, that is, its insistence on the permanent remembrance of the unity and oneness of God, the absolute Reality, which demands total surrender and submission, marks the followers of all its paths in an unparalleled way.”

Sufism is rooted in the shahada, or profession of faith: There is no God but God. He alone is Absolute and One. Everything comes from Him and returns to Him. He is the First and the Last, the Ascendant and the Intimate, and He is, of all things, Knowing (Qur’an 57, 3).

Sufism also implies closeness and absolute intimacy with the Creator. This is clearly expressed in the Qur’an: ” We are nearer to him than even his jugular vein”, and in many Qur’anic hadiths, or sayings inspired by God Muhammad:

“I am as My servant thinks I am. I am with him when he makes mention of Me. If he makes mention of Me to himself, I make mention of him to Myself; and if he makes mention of Me in an assembly, I make mention of him in an assemble better than it. And if he draws near to Me an arm’s length, I draw near to him a fathom’s length. And if he comes to Me walking, I go to him at speed.”.

Or even:

“When I love him I am his hearing with which he hears, his seeing with which he sees, his hand with which he strikes and his foot with which he walks.”

As we see, Islam is about absolute oneness.

This entails a systematic struggle against the ego, the lower self, and a purification of the soul until, as the mystic al-Ghazali said, the heart becomes a mirror that reflects only the light of God.

Women in sufism

In Sufism, men and women can reach the same rank and the same spiritual degrees.

Thus, in his work Futuhat al-Mekiyya (Revelations of Mecca), Ibn Arabi writes:

“All abodes, all levels, all attributes may belong to whom God wills, both to women and to men for whom God may will (…) [Men and women] share all levels, including that of Polo.”

Similarly, Rumi often refers to the feminine and presents woman as the most perfect example of Creation. In his work Matnawī, he states: “Woman is a ray of God. She is not just the earthly beloved; she is creator, not created.” (Helminski 2013: 6).

As for the poet and Sufi and poet El Yami (15th century):

“If all women were like those I have mentioned,

women would be preferable to men.

For the female gender is no shame to the sun,

nor the male an honour to the moon”.

Hagiographic authors

Still, it is undeniable that Islam, like all religions that emerged as liberating systems, has drifted over time towards patriarchal and misogynistic views. However, in the case of Islamic mysticism, misogyny has clearly been less prevalent than in other schools of thought and certain monotheistic traditions.

Still, it is undeniable that Islam, like all religions that emerged as liberating systems, has drifted over time towards patriarchal and misogynistic views. However, in the case of Islamic mysticism, misogyny has clearly been less prevalent than in other schools of thought and certain monotheistic traditions.

In fact, in hagiographic accounts, it is not uncommon to observe that the acceptance of women in religious affairs and in the relationship between genders in matters of spiritual knowledge was clearly more open and progressive than it is today.

Among the main authors who devoted part of their written work to hagiographies and women mystics are:

Al-Isfahāni (10th – 11th c.), who refers to the spiritual excellence of some women contemporaries of the Prophet.

Abu `AbdalRahman al-Sulami (11th – 12th c.), who wrote a work on early women saints.

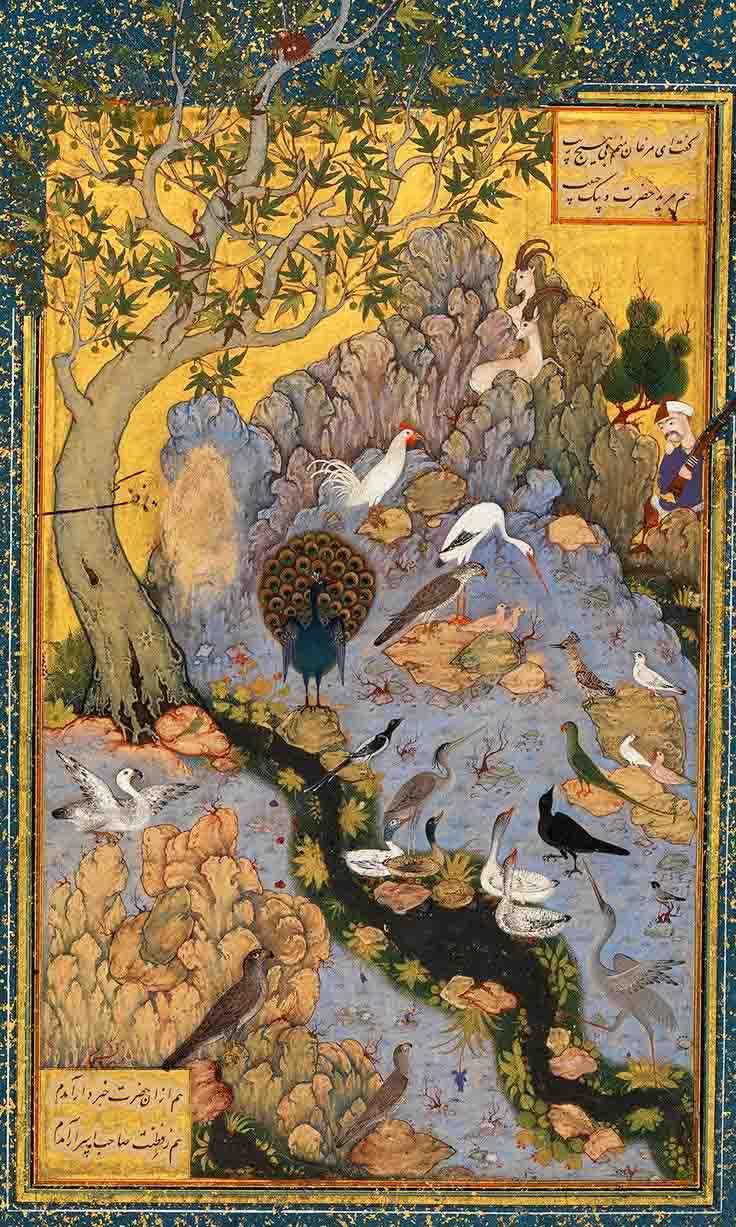

The Persian mystic Farid ud Din Al ‘Attar (12th – 13th century), who, in his Memorial of the Saints, provides the most extensive and complete biography of Rab’ia, as well as other female saints.

The Baghdadi Ibn al-Jawzi (12th – 13th century) wrote about 240 Sufi women.

Later, in the 15th century, a Damascene, Abu Bakr al-Hisni, wrote a book in which he referred only to women: the Ketāb siyar al-sālikāt al-mu’mināt (Book on the Steps of the Believing Women Seekers).

In the same century, Ŷāmi included in his Nafahāt al-uns 33 sections dedicated to women under the significant title: “Memoir of Gnostic women (‘ārifāt) who have reached the abodes of men”.

However, the author who, without a doubt, made the most references not only to female saints, but also to the female role in Islam as the principle of the All, was the great Ibn Arabi of Murcia, one of the most prolific Sufis and one of those who left the greatest written works.

It is also curious to see how for Shaykh al-Akbar, and for some others, concepts so genuinely masculine and dear to the Sufi tradition as futuwwa (spiritual chivalry) or ruyuliya (virility, in the sense of bravery, but also of spiritual and moral elevation) are not at all the patrimony of men, but also of exalted women. Thus, Ibn Arabi stated:

“The perfection of rujuliya [manhood] is found in the one we have mentioned, whether male or female.”

The servers of Allah

These women who were considered holy, that is, women who had appeased their souls, as the Qur’an says, and whose devotion to their Lord and to the Oneness was absolute, did not generally correspond to the canons found in other traditions, such as Catholicism. In Arabic, they are called Waliyat Allah, which means “close to or friends of God”. They were not necessarily chaste, celibate, submissive or vulnerable, or martyrs for that instance, nor were they necessarily associated with the men around them, although they were often ascetic and extremely virtuous. They could be teachers of men and women, celibate, married, mothers, rich, poor, socially active, solitary and hermits, erudite and illiterate; the profiles were manifold.

These women who were considered holy, that is, women who had appeased their souls, as the Qur’an says, and whose devotion to their Lord and to the Oneness was absolute, did not generally correspond to the canons found in other traditions, such as Catholicism. In Arabic, they are called Waliyat Allah, which means “close to or friends of God”. They were not necessarily chaste, celibate, submissive or vulnerable, or martyrs for that instance, nor were they necessarily associated with the men around them, although they were often ascetic and extremely virtuous. They could be teachers of men and women, celibate, married, mothers, rich, poor, socially active, solitary and hermits, erudite and illiterate; the profiles were manifold.

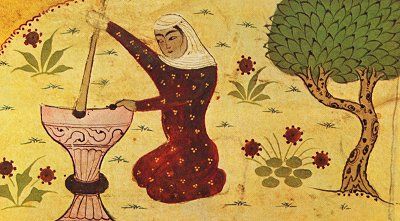

There were those who were prey to frequent raptures and ecstatic states, others were sighed with divine love or wept with longing and repentance. There were those who shared their esoteric and exoteric knowledge through exegesis and the study of Islamic jurisprudence. What is certain is that they were generally women who enjoyed a greater degree of freedom than was common at their time, and were characterized by a strong temperament.

We rarely find are women involved in the politics and power of their time, as was sometimes the case with men, especially during colonial times. There were exceptions, however, such as Lalla N’Sumar, an Algerian woman who, at the age of 24, created an army in her native Kabylia and defeating General Randon’s troops in 1846 .

In any case, all of them were, or are, women totally devoted to the purification of the soul, intimacy with their Creator, divine love and gnosis. They were ‘ibadat Allah, servants of God.

On the concept of servitude, I will quote Amina Gonzalez, from the University of Murcia:

“This theology of Servitude made these women truly free from the limitations imposed on them in their societies. These chosen “handmaids” of God could separate themselves from the mass of women who did not share the same spiritual vocation. They chose an independent life as “women dedicated to the career of the spirit”, so they could travel without a chaperone or legal guardian, mingle socially with men, teach men in public assemblies and develop intellectually in a way that was not accessible to their non-Sufi Muslim sisters”.

In relation to the concept of Servitude to attain the Divine, we have this beautiful statement by Umm ‘Alī, a Sufi woman from Nishapur: “He who is confirmed in the knowledge of servitude will soon attain the knowledge of lordship” (Sulamī 1999: 244).

Some historical women saints

The quintessential Sufi saint of early Islam is Rabi’a el Adawiya (8th centry). The perfection of her character, her great piety, her gnosis and her asceticism made her known across borders, centuries and cultures. Later mystics would know her as “the crown of men” (Smith 1984:4).

On the other hand, as we said, her biography and legends reveal a strong and temperate character, also in relation to men. This is exemplified in the following anecdote: on one occasion Rab’ia’s disciple, Hassan (presumably al-Basri), spreads his mat over the water and said to her, Rab’ia come and pray a couple of rakats. She extends hers, which remains suspended in the air, as a sign of spiritual superiority. Then she said:

“Hassan, what you did the fish also do, and what I did, the flies also do. The real issue is beyond both tricks. You have to apply yourself to the real issue” (The memorial of the Saints).

Such was her relevance, which transcended into Christian times many centuries later, that she eclipsed other great women of her time, including ‘Abda bint Shuwal and Maryam of Basra, who were little mentioned but who nevertheless accompanied her. It is believed that at that time, and unlike today, mystics were very numerous. As the Qur’an states, there were “many of the first, but few of the last”.

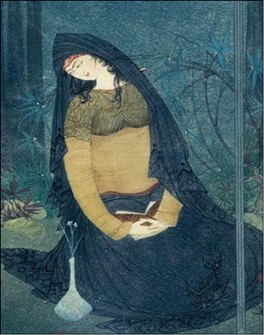

Maryam of Basra was a companion and disciple of Rābi’a and devoted her life with great intensity to divine love (mahabba li-Llah). It was not uncommon for her to fall into deep ecstasies when the doctrine of love was discussed.

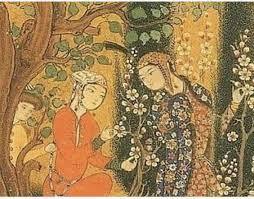

Centuries later, another woman who must have shone with her own light and who impressed due to her wisdom and stature was Nizam, whom Ibn Arabi met at the Kaaba in Mecca, while reciting mystical poems, and to whom he dedicated fiery writings and poems. He described her as follows:

“A slender young woman who attracted the eyes to herself. She adorned the gatherings and the people themselves, while at the same time she disturbed those who agreed to look at her. Her name was Nizam (…). She was the eldest of the believers, of the wise and ascetic, temperate and Mistress of the two Shrines. Grown up in the Faithful City, she appeared majestic and unbending, with a bewitching appearance and Iraqi elegance. When she was overflowing (in her speech) she was overwhelming, and if (she wished to be) concise, she was inimitable”.

Ibn Arabi was also impressed by a slave girl from Qasim al-Dawla who lived in Mecca and had the gift of covering long distances with little travel. According to him, she practised a harsh discipline of asceticism and possessed the qualities of chivalry, or futuwwa.

Moving and inspiring are also the stories of saints who shared gnosis and spiritual abodes with their spouses.

Michel Chodkievizc describes one such case as follows:

“Although Rābi’a al-Shāmiyya, often confused with Rābi’a al-‘Adawiyya, was the wife of Ibn Abi Hawāri, she is not recognised by this fact in hagiography. Ibn Abi Hawāri, who was sufficiently important on his own merits, devoted himself, with touching veneration, to his wife, whose superiority he recognised; and it was he who passed to posterity thanks to her virtues and ecstasies (Ibn al-Ŷawzi 1986, IV, p. 300)”.

In his work Futuhat al-Mekiyya, Ibn Arabi refers on several occasions to his wife, Maryam bint ‘Abdūn, as a virtuous woman who, through a vision she had, showed him the way to follow the path to gnosis.

As for the role of mothers in the transmission of knowledge, it was not negligible either. Such was the case of the great master, the father of most of today’s tariqas, or Sufi paths, ‘Abd al-Qādir Ŷīlānī (12th century), whose mother and aunt greatly influenced his spiritual life.

Women teachers

As we said, many of these Muslim saints were also great teachers, guiding women and men as well.

As we said, many of these Muslim saints were also great teachers, guiding women and men as well.

“I found in her the more trustworthy teacher in the science of the saints and in the doctrine of salvation than in any other source that came to me, apart from the Holy Scriptures”.

This statement about Rabi’a was made by Jean-Pierre Camus, Bishop of Belley, France, in the 16th-17th centuries. No less than seven centuries after his death.

In the early period (9th century), Fatima of Nishapur was the teacher of the great mystics Abū Yazīd al-Bistāmī, Dū l-Nūn al-Misrī and al-Ŷunayd.

To illustrate the great spiritual and moral power that Fatima of Nishapur had, I will mention an anecdote collected by al-Sulami, according to which the famous Egyptian mystic Dhu l-Nun, when asked about the most remarkable person he had met, replied: “I never saw anyone more excellent than a woman I met in Mecca called Fatima of Nishapur. She used to discuss wonderfully on matters pertaining to the meaning of the Qur’an (…). She is a saint from among the friends of God, Glorious and Mighty. She is also my teacher.”

Du l-Nūn further relates his encounter with an anonymous woman who conveyed to him the attributes that a Sufi should have, reminding him that the essence of knowledge, with a capital letter, is not to be found in paranormal or esoteric states, but in spiritual practice, just as Rabi’a did with Hassan.

Returning to Ibn Arabi, from among different his teachers, in al-Futuhat he singles out Fatima bint ibn al-Muthanna, or Fatima of Cordoba, a nonagenarian of special spiritual elevation whom Ibn Arabi served and with whom he lived for two years in a hut of reeds built by himself on the outskirts of Seville. He refers to her as his spiritual mother. Fatima was said to send the opening azorah of the Qur’an, the Fatiha to obtain what she desired, and she mastered the science of letters. For her anything was an object of divine contemplation. Ibn Arabi recounted that, despite her advanced age, such was her light that he could hardly look her in the face:

“She was more than ninety-five years old at the time, and yet I was ashamed to look at her face, for her face, in spite of her years, was so beautiful and lovely, because of the regularity of her features and the rosiness of her cheeks, that one would have thought her a girl of fourteen (…) She lived in constant contact with God”.

Centuries later, in the Ottoman period, al-Munawi, in his Tabaqat, pays tribute to 35 women. One of them is Fatima bint ‘Abbas (14th century), a doctor of jurisprudence and law, and a woman of mysticism. Her story shows that, at the time, Muslim women figured not only in the public sphere, but also in the religious sphere. In fact, Fatima delivered the Friday sermon in the mosque every week. This is unthinkable today.

But we must not forget the women of the so-called popular Sufism, especially in the Maghreb, a less “orthodox” Sufism tinged with animist overtones, due to the Amazigh and sub-Saharan influence.

Among these women, still venerated and inspiring, sometimes even incorporeal, who fill local place names but were never mentioned in hagiographies, are Lallā Sitti from Tremecén, Lallā Mimuna in Morocco and ‘A’iša al-Mannūbiyya from Tunisia, among many others.

The legend surrounding Mimuna is touching to say the least:

“She was a poor black woman who asked the captain of the ship to teach her the ritual prayer, but she could not remember the formula correctly. To hear it again so that she could retain it, she ran after the departing ship, walking on the water. His only prayer was: “Mimuna knows God, and God knows Mimuna”.

For, as Chodkievicz so aptly defined them, some of these great figures were simple and dumbfounded spirits, but no less elevated for that.

Translation: Alfonso Casani – FUNCI

References

De Rabi‘a Al-‘Adawiya (m. 801) a Fatima Al-YaŠrutiyya (m. 1978): modelos de santidad y feminidad, mujeres de conocimiento y maestras sufíes en el orbe islámico. Amina González, Univ. Murcia

El principio femenino de los textos cosmológicos del sufí Muhyidin Ibn Arabi (1165-1240 d. C.) Gracia López Anguita, univ. Seville

La santidad femenina en el islam. Michel Chodkiewicz

El memorial de los santos. Farid Uddin Attar

El islam cristianizado. Miguel Asín Palacios

Los engarces de la sabiduría. Ibn Arabi