Articles

The tomb of Abu Madyan in Tlemcen

Article author: Claude Addas

Date of publication of the article: 03/08/2011

Year of publication: 2009

Article theme: Fotografía, Islam.

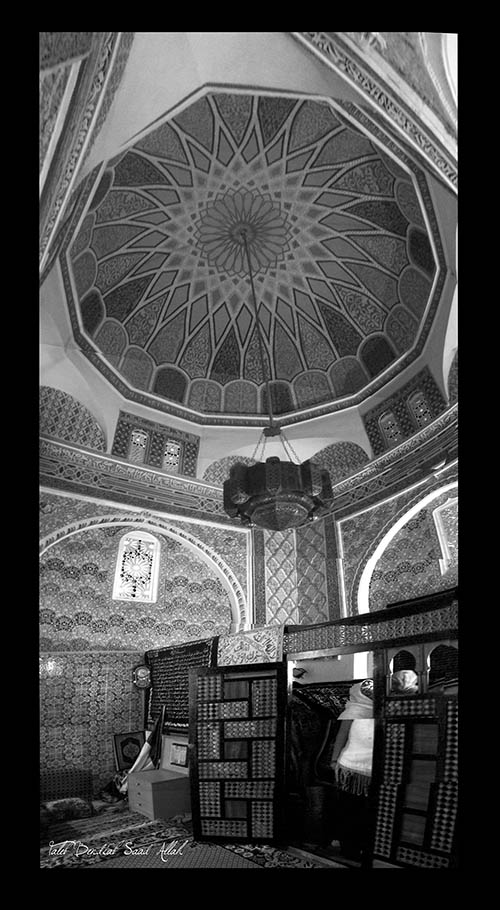

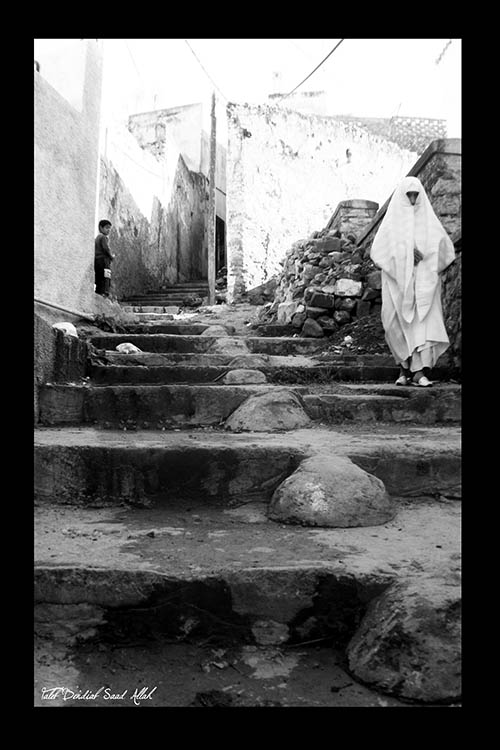

These are the pictures of the young algerian photographer Saadou Taleb, taken during his successive visits to the tomb of Abu Madyan, or Sidi Bu Medyan, as he is known there. They show the serenity and beauty of that small place in the West of Algeria.

Abu Madyan and Ibn ‘Arabi

During the research I carried out some years ago, in the course of my work on the biography of the Shaykh al-Akbar, I repeatedly came up against questions which, through lack of time and above all through lack of documentation, I was obliged to leave unanswered. I should like, here, to try to provide something of a reply to one of those questions which it seemed most important to throw light on because of its involvement in the destiny of Ibn ‘Arabi, and, more generally, in the development of the tasawwuf from the thirteenth century onwards: Why does Abu Madyan, whom he never met, have so much importance for Ibn ‘Arabi that he constantly refers to him in his work, and continually adds to his declarations of admiration and respect for him, most often giving him the title of shaykh al-mashayikh, the ‘Master of masters’?

It is true that Ibn ‘Arabi did not invent this laqab. By applying it to him, he is simply conforming to a practice which began, it seems, during the actual lifetime of the Saint of Bugia. The Arabs, I well know, have at all times shown an inordinate taste for hyperbole. Chroniclers and hagiographers very liberally give out dithyrambic titles which are not always justified: an annoying habit which Ibn Jubayr, a contemporary of Ibn ‘Arabi, and a merciless observer of the customs of his time, condemns on a memorable page of his Rihla.[1]

But in this case it is not a question of that. The author of the Futûhât never writes anything unthinkingly. For him, eulogy is not mere rhetorical decoration. The superlative which he applies to Abu Madyan must not therefore be interpreted in his writing as the result of a conditioned reflex, or even as a purely formal mark of respect towards an elder. With these words, Ibn ‘Arabi means not so much to pay tribute to the spiritual pre-eminence of the Saint of Bugia as to express the profound and sincere veneration which he has for him.

Vitality and ardour

As a matter of fact, Ibn ‘Arabi shares this veneration with many Muslims both past and present. The processions which cause a large crowd to gather round the mausoleum of Abu Madyan at Tlemcen each year during the religious festivals, bears adequate witness to the vitality and ardour of the cult of which he is the object. Two factors have contributed, it seems to me, to the development of this popular fervour: first of all, one must not disregard the strictly charismatic dimension of Abu Madyan, who drew such a crowd of disciples round him that, according to some chroniclers, the Almohad authorities suspected him of wanting to raise an army by claiming the title of Mahdi; whether it is true or not this assertion in any case exemplifies the measure of popularity which Abu Madyan enjoyed in his lifetime. Moreover, contrary to what has happened to other awliya’, who also knew a certain degree of success during their passage through this world but of whom no memory has conserved reminiscence nor any epitaph the name, the posthumous renown of Abu Madyan has notably resisted the onslaught of time, and even more implacable, the ungrateful memory of men. His reputation was in fact actively maintained and regularly nourished throughout the centuries, both by a strong oral tradition, particularly via some muwashshahat which extol his miracles and praise his virtues – one of them, recently composed by an Algerian singer, has enjoyed a great success with the Maghrebi young people – and by a wealth of more or less erudite literature.

This richness of documentation must not deceive us however. The texts are numerous, it is true; nevertheless, on reading them carefully, one discovers that they are saying the same thing, in a more or less disguised form as the case may be, so that the facts which we currently have on Abu Madyan finally do not add up to much. To the inevitable question ‘who copied whom?’ I shall reply without hesitation: an examination of the sources relating to the biography of Abu Madyan reveals that the Tashawwuf by Tadili, who died in about 627/1230, constitutes the original source from which later writers drew, adding here and there some elements of their own.

Consequently, it would be useful to recall the main points of information written down by Tadili in section 162 of this work dedicated to Abu Madyan.[2] Of the many accounts which it contains, one will remember especially the ones by Muhammad b. Ibrahim al-Ansari and ‘Ali al-Ghafiqi al-Sawwaf who heard from Abu Madyan, of whom they were close disciples, the story of the circumstances which surrounded the beginning of his vocation. Here are the principle points of note in the first account by M. b. Ibrahim al-Ansari: as an orphan, mistreated by his older brothers whom he served as a shepherd, the young Abu Madyan suffered dreadfully from his illiteracy which made him incapable of fulfilling his obligatory acts of devotion. Having resolved to teach himself, he repeatedly tried to escape, but each time his brothers caught him and punished him severely. However, thanks to miraculous intervention which dissuaded them from keeping him any longer, he gained permission to leave.

From the village of his birth, situated near Seville, the youth arrived, after various vicissitudes, at Fez where, first of all, he learned the rudiments of the religion. Then, wanting to know more, he attended the courses of some fuqaha’, only to realize very quickly that he did not remember anything of what they said. Very fortunately, he met Ibn Hirzihim – a famous faqîh-sufi – whose teaching went, he said, ‘straight to his heart’. Having heard people speak about Abu Ya’za, famous during his lifetime for many miracles, Abu Madyan went to visit him with a group of friends. The rest of the story is well known; let’s listen, nevertheless, to the account that Abu Madyan gave of it to his disciple Muhammad al-Ansari:

When we arrived at Mount Ayrujan we went into Abu Ya’za’s house, and he welcomed everyone except me. When the meal was served, he forbade me to eat; so I went and sat down in a corner of the house. It continued like that for three days, each time the meal appeared, and I got up to eat, he sent me away; I was exhausted with hunger, and I felt humiliated. After three days had gone by, Aba Ya’za left his seat: I sat down in the place where he had been, and rubbed my face. Then I raised my head and opened my eyes: I saw nothing, I had become blind. During the whole night I did not stop crying. The next morning Abu Ya’za called for me and said: ‘Come here, Andalusian!’ I went close to him. He put his hand on my face, and immediately I recovered my sight. Then he massaged my chest with his hands, and said to those who were present: ‘This one will have a great destiny!’

Abu Ya’za then allowed Abu Madyan to go, but not without warning him first of the dangers that he would meet on the way; of course, things happened just as Abu Ya’za had predicted. ‘After that,’ concludes Abu Madyan, ‘I did not stop travelling until one day I arrived at Bugia where I stayed.'[3]

The account by ‘Ali al-Ghafiqi is noticeably different. The childhood of the saint, which it seems was fairly unhappy, is passed over in silence, as are the precise circumstances of his departure for the Maghreb; Abu Madyan confines himself to telling his disciple that he left his native village to go to the Maghreb. The version he gives to Ghafiqi about his stay in Fez contains more facts than that conveyed by Ansari, particularly concerning his teachers and his initiatory education. Thus he specifies that Ibn Hirzihim taught him the Ri’âya by Muhasibi, and the Ihyâ’ ‘Ulûm al-dîn by Ghazali, and that he studied, besides, the Sunan by Tirmidhi under the direction of Abu-1-Hasan Ibn Ghalib, another faqîh-sûfi, and a disciple of Ibn al-‘Arif.

Initiation in the Way

Abu Madyan also revealed that he was initiated into the Way (akhadhtu tarîqat al-tasawwuf ‘an) by Abu ‘Abd Allah al-Daqqaq – a Sufi whom hagiographical sources[4] present to us as a rather eccentric person, who walked about the streets calling out that he was a saint – and Abu-1-Hasan al-Salawi, whom I have been unable to this day to identify.

Lastly, Ghafiqi’s narration is the first to give an account of the episode of the gazelle, which was to become legendary, and which I summarize as follows:

When he was a student in Fez, every time he had learnt a verse of the Qur’an, or a hadîth, Abu Madyan used to isolate himself in a hermitage, and practise this verse or hadîth until he obtained the fath, the enlightenment proper to the practice of the verse or hadîth in question. The place that Abu Madyan had chosen for his retreat was a ruined site in the mountains, near the coast. A gazelle regularly came to visit him there, and, far from being afraid of him, sniffed him from head to foot then settled down by his side. One day, however, after having smelt him in this way, the gazelle gave him a disapproving look and ran away; Abu Madyan then realized that the presence on his person of a sum of money was the cause of this unusual behaviour, and he got rid of it immediately. The last but not least piece of information to remember from the Tashawwuf concerns the death of Abu Madyan. Curiously, Tadili is extremely concise about this: ‘He was ordered’, he writes, ‘to present himself in Marrakesh. He died on the way at Yassir in 594, or according to some, 588; he was buried at ‘Ubbad, just outside Tlemcen.'[5] A few lines further on he informs us – relying on the testimony of a person who was present at the death agony of Abu Madyan – that the saint’s last words were ‘Allah al-Haqq’ or, according to another account, ‘Allah Allah.’

Tadili’s laconicism about this event, and, more precisely, about the reasons which impelled the sultan to command Abu Madyan to present himself in Marrakesh, is, at the very least, surprising. Would the author of the Tashawwuf, who was close to several of Abu Madyan’s disciples, some of whom accompanied the master on his last earthly journey, have been unaware of the reasons for this sudden and fatal summons to the palace? It is rather unlikely; however, he keeps quiet about it.

This is a silence which is all the more striking since it contrasts with the prolixity Tadili’s successors displayed on this subject which, moreover, has continued to divide them over the centuries. In fact, when one draws up an inventory of their texts, and collates the accounts which they give of this tragic event, one notices that two diametrically opposed theories, each one tirelessly upheld and repeated by an almost equal number of partisans, have prevailed amongst Arab historians.

For reasons which unfortunately they do not specify, Western specialists of Islam have always chosen to uphold the version which interprets the facts in a political way, and which I summarize here, relying on the account written down by Ibn Qunfudh in his Uns al-Faqîr Wa’izz al-Haqîr:

Following a malicious denunciation, the Almohad Sultan, Ya’qub al-Mansur, ordered the governor of Bugia to have Abu Madyan brought to Marrakesh under escort. The announcement of this disquieting royal summons provoked a strong emotional reaction amongst the followers of the master. The latter tried to reassure his disciples: ‘Shu’ayb’, he told them, ‘is a weak old man, incapable of walking; now, it has been decreed that his death will take place in another country. As it is inescapable that he should get there, God has arranged it in such a way that someone will carry him gently to the place of his burial, and transport him in the best way to his determined end. However, those who are asking for me shall not see me, and I shall not see them.’ Abu Madyan then left accompanied by the royal escort. Having arrived on the outskirts of Tlemcen he asked: ‘What is this place, where we are now, called?’ – ‘Al-‘Ubbad’ (the devout) – ‘How pleasant it would be to rest here!’ The saint passed away shortly afterwards.[6]

Ghubrini is the first, to my knowledge, to put forward this version in the ‘Unwân al-Dirâya,[7] which he wrote down about a century after Abu Madyan’s death; he was to be followed by Ibn Qunfudh (d.809/1406), Ibn Maryam (d.1011/1602),[8] Ahmad Baba al-Tumbukti (d.1036/621),[9] and Maqqari (d.1041/1631).[10] It is interesting to note that the first two, Ghubrini and Ibn Qunfudh, did not deem it necessary to specify the nature of the anonymous accusation made against Abu Madyan, perhaps because it was more obvious in their time, which was relatively close to the time when Abu Madyan lived.

Ibn Maryam, Maqqari and Ahmad Tumbukti, who were much later, felt the need to be more precise; they point out that the anonymous informer convinced Sultan Mansur that the Saint of Bugia constituted a danger to the realm, on account of his resemblance to the Mahdi, and his large number of disciples. These authors also specify that the informer was one of the ‘ulama’ al-zâhir, the doctors of law…