Notes of history

Qabbani and al-Bayati: two Arab poets in Madrid

Rosa Isabel Martínez Lillo (Autonomous University of Madrid)

Two poets and the same city. Two contemporary Arab poets, two different moments in their lives, and the same city that was once Andalusian. Two starting points: one of water and air, Syria, the other of earth and fire, Iraq, and the same capital at different times. Two men, two Arab poets who arrive in Madrid with two different backgrounds, with expectations, experiences and perhaps illusions that only they know.

One, Qabbani, in his early 40s, with a confessed love for our Spanish reality, with a thirst for Spain, with his heart and the pores of his skin wide open, permeable, ready to experience in the flesh the temperament of al-Andalus rediscovered.

The other, al-Bayyati, from a mature age, from the vantage point of the advanced 50, and with a sad burden of exile on his back. With the flame of a constant and unwavering political and poetic commitment.

How did each of them live their experience in Madrid? How did each of them live the Spanish capital?

Let us look at both journeys separately in order to converge at the same point of arrival.

Nizar Qabbani (1923-1998): Madrid of Springs and Roses[1].

Although his stay as a diplomat at the Syrian Embassy in Madrid began in 1962 and lasted until 1966, Qabbani was by no means a stranger to the Spanish reality, as can be seen in the following poem dated 5 August 1955, which he wrote in Madrid:

In Spain, I needed no inkwell,

nor ink with which to quench the thirst of paper.

The eyes of Morena Rosalía

They sprinkled my soul with their black nostalgia.

The eyes of Morena Rosalia

-black inkwell to sink in-

drank my life.

With a seashell, dreadful…

Like an Arab palanquin

that dug its fate in the distance,

digging its fate with mine.[2]

He arrives, then, in a reality already known and perhaps also loved. From the beginning there was a strong attraction, I wonder if it was mutual, between the poet and the city; a city that Qabbani savours by walking and allowing it to penetrate him through his five senses. Every place and every time is susceptible of becoming joy, pleasure, happiness, everything carries within it the germ of love and beauty: from his place of work in the Plaza de la Platería de Martínez, near which he liked to have lunch at El Rábano – or Rabanito, as he called it –[3] to his house in Calle Juan Ramón Jiménez (did fate want to bring him even closer to Spanish poetry?), and in between the walks of a city in eternal springtime.

A city and a language «open to the sun, to the sea, to the plains of grapes and olive trees»,[4] in his own words, which the poet gladly learns and feels from the work of Spanish poets, and from the translations of his own verses:

During a certain period, my relationship with the Spanish language reached a degree of infatuation, especially when it managed to fill me completely. The Spanish Arabist Pedro Martínez Montávez was then preparing the translation into Spanish of some of my poems […]. I remember now the pleasant hours I spent with my friend Pedro in my house in Madrid, chatting, discussing, going over the drafts of the translated poems.[5]

Madrid, as well as being singular, is a whole with other Spanish cities (Seville, Granada and Cordoba, essentially) in this «pink stage», a whole, a plenitude which, while in al-Bayati refers to the East in its first stage, in Qabbani it is drawn as a constant journey to al-Andalus/al-Sham and al-Sham/al-Andalus. Travelling, living perennially and renewing between here and there, the before and the now:

I have never wanted to be buttonhole of a suit,

the thread of a suit,

except in the Army Museum in Madrid:

the suit is Boabdil’s and the sword is his.

Tourists circulated without stopping

in front of the suit and the sword,

but I…

A thousand reasons bind me to this suit and its owner.

And just as an orphan stares down at his father’s youthful portrait,

so I stood before the closed showcase.

Pleading in front of that embroidery,

devouring, thread by thread, that fabric…

And yet,

Boabdil did not leave me alone in the city.

Because every night,

dressing in his cloak,

he would leave his display case in the Army Museum

and came with me for a stroll along the Castellana…

And he would show me, one by one,

All his Andalusian heiresses.[6]

But it is not only a journey through times and places, an Andalusian experience in the last case, and a personal emotion of attachment to a city and a language. The Madrid experience, which, as I say, is one with the whole, is also the «stage of historical and nationalist emotion».[7] A stage whose outcome the poet would experience much later and which he would capture, with defiance and palpitating emotion, in «El último andalusí». [8]

Moreover, I believe that this nationalist experience as a Damascene, Syrian, Mediterranean, Arab man, in short, coexists with his own personal experience as a man and poet, as a human being, as a child born of love:

From Madrid, good morning…

What news of jasmine

to tell you?

With it I entrust you, my mother,

that little girl

who was my father’s great beloved,

and whom he pampered

as his own daughter.

Offering her coffee from his cup, giving her food and drink,

immersing her in all his clemency.

And my father died,

But she still lived dreaming of his return,

looking for him in the corners of her room,

asking for his newspaper

and for his cloak.

Asking

when from the emerald of her eyes

Summer would come.

For her to spread over his hands

the golden dinars.[9]

A Madrid experience that embodies an extremely deep and extensive dimension of his wayd taariji mustahil (وجد تاريخي مستحيل) or «impossible historical experience»,[10] and, I wonder, whether it does not lead, beyond the journey, to perspective, to a vital attitude. I wonder, finally, if this experience is not the birth of his «other self», of an antidote which, later on, would cure him of the harshness that being a full Arab, convinced, conscious, an Arab of reason, body and soul, entails in the contemporary world.[11]

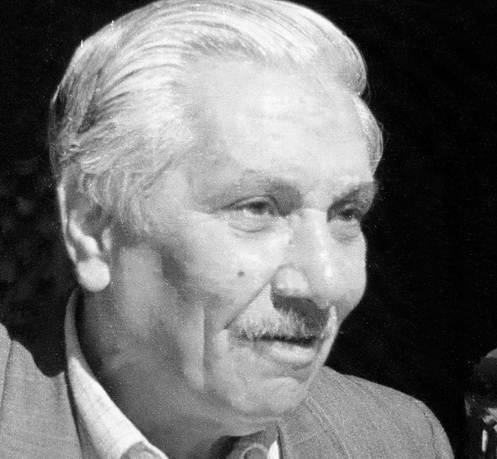

Abd al-Wahhab al-Bayati (1926-1999): Madrid of autumns and twilights.[12]

To begin to speak of this great Iraqi Arab poet may be difficult, but having done so, the words flow of their own accord. Perhaps referring to him is like revealing a secret, deciphering the enigma, his own enigma, his own personality. Abd al-Wahhab al-Bayati often spoke with silences, sometimes with glances that transported us to remote times and hidden places, but always being true and profound.

I believe that trying to unveil his experience in Madrid requires a long reflection on the following question: how to link the inner reality, the poet’s most intimate one, with the external one, Spain, Madrid in our case?

Al-Bayati, a revolutionary Arab poet, is assigned as a cultural counsellor at the Iraqi embassy in the Madrid of Franco’s Spain, whose political doctrine he did not share. His family accompanied him on this assignment; his kind and loving wife Hind and his charming daughter Asma, who took care of him at all times, are two key pieces in his life and particularly in this adventure in the Spanish capital.

I think, then, that from the beginning he establishes a bond of a certain remoteness with the city, of living it somewhat at a distance, of observing it from the outside.

Madrid, on the one hand, with its language (of which al-Bayati only learnt a few words), its ideology, its present, and the poet, living intensely his Arabic language, living intensely the reality of his beloved Iraq almost in exile, and in a familiar environment.

Madrid, in this first moment, is experienced from an essentially political point of view, from an ideological militancy that leads the poet to relate it to other cities in the East and West:

At the gates of Madrid we wait for you for a long time

and through your eyes, comrade of the sun, we colour the fields

the earth by the ancient souks of Tehran,

and we ate thorns and prickly pears in the bloody neighbourhoods of Chicago.

At the gates of Madrid. In the ancient souks of Tehran.

Over the dead, and in the bloody quarters of Chicago.[13]

But over time, the city will acquire its own personality, which will inevitably transport the artist to the Andalusian sphere; to the broader, Spain, and to the more specific, Andalusia, Lorca:

Death in Madrid,

in your veins blood,

and snow and daisies under your feet.

The feasts of Spain have no more people

Nor the sorrows of Spain have any limit.

For whom, then, do these bells ring?

Lorca is silent,

the blood is in the glasses of roses,

the night of Granada, the ice, they die under the hats

of the black guard,

and the children cry

in the cradles.

Lorca is silent,

and you in Madrid, with your weapons:

pain, words and volcanoes

that spew lava.

For whom, then, do these bells ring?

If you are silent, and blood

stains the roof, the forests and the summits.[14]

Yes, it is true that all his personal wayd (وجد), in its sense here of painful emotion, of the Iraqi poet, comes to the surface everywhere, but it is no less true that the Spanish city has already acquired a more personal nuance. Surely the man’s personal experience of the city also played a part in this, as a bridge begins to be built between the two realities: the bridge of the poets, of the Arabists, of the intellectual and cultural life of the Madrid of the time, with which al-Bayati is now creating links.

The poet shared poetic evenings and conferences with professors, poets, intellectuals and artists: professors Pedro Martínez Montávez, Carmen Ruiz and Federico Arbós, among others. Poets and intellectuals with whom al-Bayati also frequented one of the most savoured spaces of all cities: the world of the cafés.[15] Thus, a link with the city of Madrid appears, perhaps more corporeal, more physical and certainly more personal, more intimate. The poet likes to frequent two cafés: the now defunct Manila on Gran Vía[16] and the one in the Hotel Husa Princesa, next to El Corte Inglés in Argüelles, now converted into a Starbucks Coffee. He went there with his Spanish friends, already mentioned, and with his Arab colleagues and friends, among them the Egyptian journalist Talaat Shahin, the Iraqi artist Yaafar Kaki and Professor Waleed Saleh, with whom his friendship lasted until the end of his days.

Al-Bayati would come to the café, sit, observe and discuss, talk for hours on end, sometimes in words, sometimes in silence, depending on his interlocutor. His gaze, however, always reveals truth, depth, and a beyond that is not always revealed to all. And although his Spanish was reduced to little more than «another coffee», his gaze and his deep feeling for Madrid also go beyond, much beyond:

Your eyes are Madrid, which I recover.

Your eyes, Qandahar.

Two lakes through palm groves and wastelands of fire

in which I sink and burn.[17]

Thus, after all, with all the dramatic experiences that followed[18], which, as he himself said, did nothing more than «intoxicate his spirit», perhaps his time in Madrid was synonymous with freedom, tranquillity in a certain sense, and satisfaction[19].

A shared point of arrival?

Despite their very different experiences, the different nuances lived in the same city, despite Qabbani’s springs and al-Bayati’s autumns, perhaps they shared the same season: that of winter, when the dry cold of the city penetrates your bones and you have to seek warmth, shelter and protection.

Both coincide, yes, in this Madrid winter. One, al-Bayati, with wet eyes, in solidarity with the marginalised, drawing a portrait somewhat in the manner of the most lucid Goya, in his «Madrid at Christmas»:

In the Plaza de los Cinco

Three Wise Men.

The Messiah passed by, furtively, with an olive branch

and his pale face

carved in hyacinths.

There in the square stood an outcast fellow

wearing a cloak of autumn leaves.

And a girl, beside him, was drinking alcohol.[20]

And the other, Qabbani, with his eyes already sheltered, warm and full of the future, in a winter that is but the beginning of another year, of that great love that lived in our capital, of that winter of «New Year’s Eve in Madrid»:

If you had been in Madrid on New Year’s Eve,

we would have gone together

to an old tavern

where we could be alone together,

so that our hands could search for each other in the shadows.

[…]

If only you had been in Madrid on New Year’s Eve.[21]

It is true that other Arab poets have lived, with greater or lesser intensity, the Madrid experience in much shorter, more punctual stays: Adonis, Mahmud Darwish, Samih al-Qasim, Ahmad Suwaylam, to name just a few, but I believe that the experience of Qabbani and al-Bayati, with all their encounters or misunderstandings, is unique, incomparable, singular. And surely it is not only the city that left its mark on the poets, for whenever I pass by al-Bayati’s house in the Castellana an indecipherable glance appears, and when I walk past Juan Ramón Jiménez a smile appears in the sky.

Article taken from: Nizar Qabbani y Abd al-Wahhab al-Bayati: Dos poetas árabes en Madrid

This article is available in Español

Notes

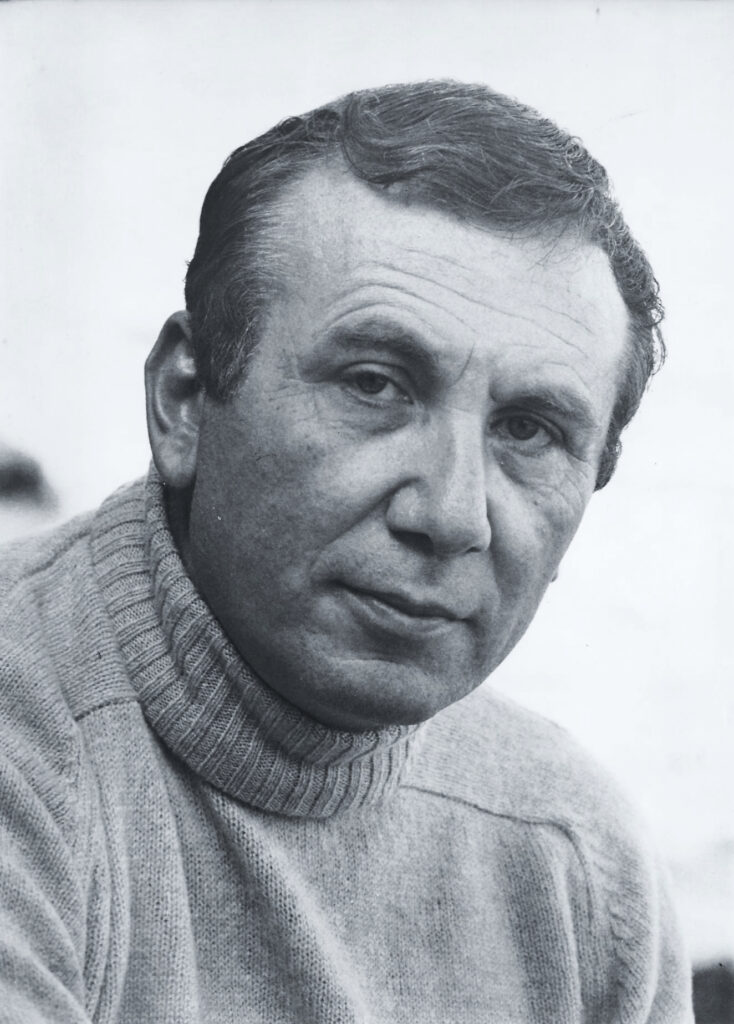

[1] I am grateful to Professor Pedro Martínez Montávez, my father, for all the verbal and written information about his experience with the poet in Madrid. Personally, although I remember seeing him when I was very young, I can only say that I met him in person in Iraq, at one of the Merbad poetry festivals, back in the 1980s, when I was living in Cairo, where I was working on my doctoral thesis.

[2] Nizar Kabbani, Poemas amorosos árabes (transl. and preface by Pedro Martínez Montávez), 3rd enlarged edition, Madrid: Instituto Hispano-Árabe de Cultura, 1988, p. 213.

[3] He had a predilection for a good plate of squid in its ink!

[4] Nizar Kabbani, op. cit., p. 227.

[5] Ibid., p. 226. It is noteworthy that Professor Pedro Martínez was not aware of the poet’s knowledge of our language until much later, since the conversations between the two were always in Arabic.

[6] Pedro Martínez Montávez, Exploraciones en literatura neoárabe, Madrid: Instituto Hispano-Árabe de Cultura, 1977, p. 15.

[7] Ibid., p. 228. The poet’s words refer to the whole Spanish experience.

[8] Published in Idearabia, Madrid, no. 2, September 1998, pp. 47-50, translation and notes by Pedro Martínez Montávez.

[9] Ibid., p. 21.

[10] In translation by Professor Pedro Martínez Montávez.

[11] This is my idea, the embryo of which is to be found in the article «Alándalus: duende poético que cura la extrañeza», presented as a lecture at the IX Foro Ibn Arabi: La memoria al servicio de la humanidad, directed by José Monleón, held in Mérida and Hornachos from 30 September to 1 October, and which I will develop at length in the forthcoming book Alándalus… desde la otra orilla (el Sham).

[12] Although my relationship with the Iraqi poet was much closer, as I knew him personally when I was studying Arabic Philology at the Autonomous University of Madrid and shared a few coffees with him, both in Madrid and in Baghdad, the truth is that al-Bayati spoke to me more with silences and glances than with words. I am grateful for all the documentation provided by Professors Pedro Martínez Montávez and Waleed Saleh, and the testimonies of María Mercedes Lillo, my mother, and the Iraqi artist Yaafar Kaki.

[13] Pedro Martínez Montávez, op. cit., p. 68.

[14] Ibid., p. 70.

[15] Anecdotally, let us say that on some occasions he also went to discos, such as the centrally located Boccacio, where he only went to watch.

[16] On the corner of Gran Vía and Jacometrezo, where there is now a Benetton chain shop.

[17] Pedro Martínez Montávez, op. cit., p. 71.

[18] Since the tragic death of his daughter Nadia in 1990, everything has been sorrow: the burning of his library, exile in Amman….

[19] Professor Waleed Saleh uses precisely these last two terms in his illustrative and heartfelt article: «al-Bayati fi-sanawati-hi al-ajira wa-tanahhudat al-bahr» [al-Bayati in his last years and the sighs of the sea], al-Kalima, no. 11, November 2007.

[20] Abdel-Wahhab al-Bayati, Love Greater than Myself (sel., transl., preface and notes by Pedro Martínez Montávez), Madrid: Asociación de Amistad Hispano-Árabe, 1985, p. 81.

[21] Nizar Kabbani, op. cit., pp. 129-131. Due to the length of the poem, only the first stanza and the last line are included.