Articles

More than a sacred text, the Qur’an as cultural heritage

Article author: Juan Pablo Arias Torres and Pablo Roza Candás

Date of publication of the article: 07/07/2025

Year of publication: 2025

After the Christian conquest, and despite the successive prohibitions to which the Hispanic Islamic minorities were subjected, the Qur’an was kept alive in their hands through clandestine prayers and aljamiada translations, preserving their faith and culture.

Few books in history have aroused and continue to provoke, in their complex universality, such disparate emotions as the Qur’an. The holy book of Islam has been and continues to be the object of devotion, veneration, and admiration, but also of dispute, controversy, and confrontation. Between fervour and flames, the Qur’an stands as a core element of our past and present, of encounters and disagreements that have, in one way or another, shaped cultures, identities, and ways of thinking.

According to traditional accounts, the history of Islam’s holy book began one night in 610 in the solitude of a cave on the outskirts of Mecca, where Muhammad received the first of several revelations of God’s word through the archangel Gabriel. This divine message, which continued throughout the Prophet’s life, was recorded after his death in the form of a book divided into 114 surahs or chapters, each of which is divided into a variable number of ayats/ayahs or verses.

The exhibition «Los latidos del Corán. La vida del libro sagrado entre mudéjares y moriscos» reveals the richness of this Hispanic Islamic tradition and shows us the Qur’an as a core element of cultural life on the Iberian Peninsula and, therefore, in Europe.

Since then, the Qur’an has been the backbone of the life of believers and the community, in religious, social, and political terms. It is their driving force and heart. And so it was among the last Muslim minorities in the prosperous and turbulent Spain of the 15th to 17th centuries, first among the Mudejars and later among the Moriscos. The exhibition «Los latidos del Corán. La vida del libro sagrado entre mudéjares y moriscos», which can be seen at the Royal Hospital of Granada until October this year, allows us to learn about a moment in our past in order to understand today why the Qur’an has played a decisive role in the historical construction of our reality.

Who were the Mudejars and the Moriscos?

The expansion of the medieval Christian kingdoms towards the south of the Peninsula led to the assimilation of a large Muslim population, which until then had been the owner and proprietor of the territory, Al-Andalus. Initially authorised as Mudejars to practise their faith with limited freedom, the situation changed drastically at the beginning of the 16th century with the forced conversion of these Muslims to Christianity. Officially Christian, the now Moriscos continued to practise Islam in secret in their homes, creating a unique form of Islam adapted to the adverse conditions of the time.

The uncompromising stance of Christian authorities towards the unorthodox identity of these Spanish Muslims resulted in the prohibition of the Arabic language and the cultural practices of these minorities, although it is true that since the 15th century, there has been a conscious assimilation of these communities into the dominant Christian culture, without them renouncing their Muslim identity.

While the people of Granada and Valencia continued to use Arabic until relatively late, the Castilians and Aragonese gradually forgot it. The abandonment of the sacred language, far from resulting in an impoverishment of Islamic culture, led to the naturalisation of an indigenous Islam, now expressed mainly in the Romance language. This linguistic situation, together with more or less clandestine religious practice, would be decisive in the formation and transmission of the Qur’an in the Iberian Peninsula.

The uniqueness of the Qur’an on the Peninsula

Even after Arabic was abandoned, the Qur’an continued to be copied in its entirety in this language until the end of the 16th century, preserving the models of the previous Andalusi tradition. Among these manuscripts, there are some very significant pieces of outstanding quality, such as the so-called Gayangos Qur’an (Royal Academy of History, ms. 11/10619), from the town of Aranda de Moncayo in Zaragoza, or the magnificent copy from Segorbe (Municipal Archive).

In contrast to these rare and unusual examples of complete Qur’ans, which bear witness to the communal use of the sacred text, the uniqueness of Mudejar and Morisco Qur’anic production is evident in its typology and language. Thus, most of the Qur’anic copies from this period are characterised by a textual model composed of a selection of surahs and verses that respond to the basic liturgical needs of the believer.

This unique Hispanic model, similar in essence to that found in other Islamic traditions, is usually accompanied by its Aljamiado translation (Romance in Arabic characters), that intertwines with the Arabic text in an interlinear or consecutive manner. Furthermore, these translations are often enriched with exegetical (i.e., explanatory) commentaries in order to facilitate the interpretation of the divine word for non-Arabic-speaking readers.

These copies of the Qur’an usually appear in various volumes accompanied by other practical chapters, often related to the life cycle of the believer; thus, the description of the ritual of the indispensable ritual purification, of the prescribed prayers and their times, of the funeral protocol, as well as other Islamic traditions and rites.

Alongside the Qur’ans in Arabic or Arabic-Aljamiado, a few monolingual Romance copies have also been preserved. The only complete copy that has survived to this day is the so-called Qur’an of Toledo (Biblioteca de Castilla-La Mancha, ms. 235), which is also a true gem of Islamic-Spanish literature, as it is the first preserved translation of the sacred text into a European vernacular from Arabic.

With the inevitable and sudden expulsion of the Moriscos from the Peninsula in the early 17th century, their most precious possessions, including the Qur’an, were hidden by their owners in their homes, between walls and false ceilings, perhaps in the hope of one day returning.

And despite the loss of Arabic, reading, reciting, and memorising the Qur’an in the sacred language was a pious act for these minorities, rewarded with many divine blessings. Mudejars and Moriscos worked hard to learn the basic notions of Arabic that were essential for these purposes. Thus, textbooks such as those from Hornachos (Biblioteca de Extremadura, ms. FA-M 3), with which the Moriscos were introduced to Arabic writing, are a good example of the materials used in these educational contexts.

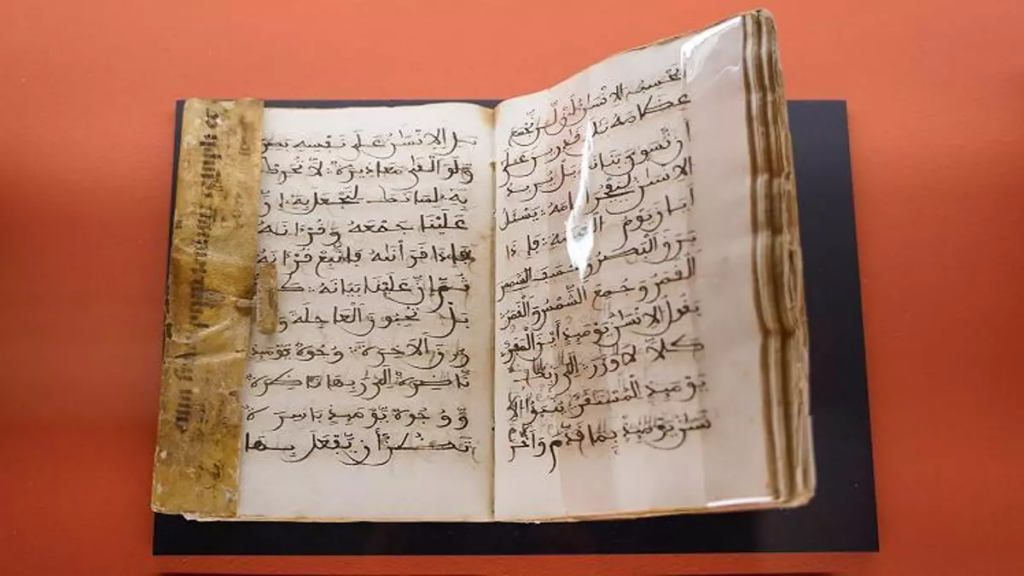

More remarkable are the Qur’anic selections with the chapters in reverse order (from Calanda, in Teruel), which, beginning with the final, shorter chapters, allow for progressive memorisation of the text. Although this mnemonic method is known in other Islamic societies, the Hispanic uniqueness lies precisely in the use of paper as the medium on which this reverse Qur’anic content is recorded.

The Qur’an, its uses and properties

Alongside canonical liturgical uses, the text of the Qur’an was employed by Mudejars and Moriscos in other contexts and ritual practices belonging to the sphere of popular religiosity; unorthodox uses that still persist in the lower classes of contemporary Islamic societies. The Qur’an is read, recited, listened to… but also drunk. Anušras, or potions, based on Qur’anic verses written with saffron in bowls and dissolved with rainwater, are just one good example of the many popular uses of the holy book. Amulets, talismans, spells, and divination formulas draw on the divine word, which is used as an enhancer of the magical remedy and ensures its effectiveness in combating all kinds of evils and ailments.

Alongside canonical liturgical uses, the text of the Qur’an was employed by Mudejars and Moriscos in other contexts and ritual practices belonging to the sphere of popular religiosity; unorthodox uses that still persist in the lower classes of contemporary Islamic societies. The Qur’an is read, recited, listened to… but also drunk. Anušras, or potions, based on Qur’anic verses written with saffron in bowls and dissolved with rainwater, are just one good example of the many popular uses of the holy book. Amulets, talismans, spells, and divination formulas draw on the divine word, which is used as an enhancer of the magical remedy and ensures its effectiveness in combating all kinds of evils and ailments.

The Qur’an also plays a decisive role in the transition between life and death. The letter of the grave, the pit, death, or the dead, such as the one from Morata de Jalón (Zaragoza), is a mortuary talisman that accompanied the deceased on their journey to the afterlife. This letter, with its profession of faith as a Muslim, was placed among the shroud, in the hand or on the cheek of the deceased, serving as a safe-conduct before Munkar and Nakir, two terrible angels who would visit and interrogate them in the cold darkness of the tomb.

The hidden Qur’ans

With the irreparable and sudden expulsion of the Moriscos from the Peninsula in the early 17th century, their most precious possessions, including the Qur’an, were hidden by their owners in their homes, between walls and false ceilings, probably in the hope of returning one day. At the end of the 19th century, the most important discovery of Arabic and Aljamiado manuscripts to date was made in Almonacid de la Sierra, a small town in the province of Zaragoza. The hundred or so manuscripts that appeared among the ceiling beams of what appears to have been a copying workshop are an eloquent testimony to the important secret publishing work of these Islamic minorities.

The importance of these and other findings marks the beginning of modern scientific research on the written culture of the Mudejars and Moriscos.

Although less numerous, other concealments and discoveries are of notable interest due to their symbolism. Such is the case of the pages of the Qur’an (Historical Documentary Collection of the Courts of Aragon, ms. D-1) that Muslim craftsmen (masons) placed between the ceilings of the throne room of the Catholic Monarchs in the Aljafería Palace in Zaragoza, as proof that there is no power greater than that of God.

The importance of these and other findings, which include hundreds of manuscripts, marks the beginning of modern scientific research on the written culture of the Mudejars and Moriscos. The European Qur’an (EuQu), Deciphering Qur’anic Dynamics (DeQuDy) and Aljamiado Qur’an (CorAl) projects, led by CSIC researchers, reflect the interest and vitality of these lines of research, in which the Qur’an occupies, as one would expect, the most prominent place, and becomes, surpassing other narratives, not only a decisive text for the religious life of these Hispanic Islamic minorities, but also for the cultural and intellectual life of the Iberian Peninsula and, therefore, of Europe.

Source: El Diario

Cover photo: Qur’anic selection in reverse order from the 16th century ©UGR.