Articles

Emerging Libyan artists to watch and learn

Arts and culture writer Naima Morelli selects five Libyan artists for the Middle East Eye, to learn and understand the political and social situation lived in Libya and its diaspora. With the ongoing political and economic instability in Libya, many of the country’s artists have left the country in search of a better life. Yet, no matter the location, their contribution to Libya’s art scene persists, with emerging Libyan artists – both at home and in the diaspora – contributing varying perspectives on the country’s complicated history.

While in previous decades, more established artists struggled under strict censorship, gagged by former Libyan leader Muammer Gaddafi’s authoritarian regime, younger Libyans today are often bolder in their expression.

Artists like Yousef Fetis, Matug Aborwai, Mohammed Bin Lamin, Hadia Gana and Tewa Barnosa are all voicing socio-political concerns in different forms, as well as speaking to the recent conflict and the civil strife.

The work Silent Protests by Tewa Barnosa exemplifies this newfound combative spirit. This is an installation consisting of 50 bricks, each one bearing a different protestor statement. Some speak of the horrors of the civil war, others are slogans written in dark humour describing troublesome social, political, historical and religious events.

Some of the bricks in ‘Silent Protests’ by Tewa Barnosa read ‘I want to live before I die’ and ‘Death is no longer terrifying; this life is more terrifying’ (Tewa Barnosa)

However, the threat to freedom of expression remains, says Benghazi-based artist Shefa Salem.

“You never know who will see it and attack you,” she says. “There are so many different factions and groups […] For example the Islamic conservatives, or the people behind this war, or even the government. There are so many considerations that must go into making work.”

The conflict has also made it more difficult for artists in different parts of Libya to meet, with the risk of encountering warring factions still high. Transporting their work is also problematic.

“We don’t have proper shipping and it’s risky for the art pieces; they can easily get damaged,” says Salem. “Sometimes you need to carry paintings yourself, and the only way to travel from Tripoli to Benghazi is by road. Air travel is not available at the moment.

“Also, the coastline road is closed because of the war, so you have to take a long detour. It’s challenging, but it’s still possible.”

“I won’t say you need to stay in Libya to make Libya better, I myself would flee given the chance. You can do a lot for Libya from abroad, given that you have a sense of belonging.”

Libyan artists in the diaspora however, many of whom initially travelled abroad to study and never returned, benefit from greater access to events and resources to help them produce and develop their art.

“They are also more aware of what is happening in the international art world,” says gallerist Elageli. “They have access to alternative ways of seeing and thinking.”

And despite the distance, diaspora artists continue to support the arts scene in their native country, launching a number of initiatives aimed at raising international awareness of the work of Libyan artists.

A prominent example is Tewa Barnosa’s WaraQ Foundation for arts and culture, a not-for-profit organisation that aims to revive the Libyan art scene by supporting critical dialogue. The artist started it in 2015 in Tripoli and it is now operating from both Libya and her base in Berlin.

In terms of global reach, London-based Noon Arts Foundation directed by Elageli, set the tone for an international conversation through the curation of successful exhibitions in London, Malta, Treviso and California.

“I won’t say you need to stay in Libya to make Libya better, I myself would flee given the chance,” says Salem. “You can do a lot for Libya from abroad, given that you have a sense of belonging.”

The following is a list of some of the most promising emerging Libyan artists working today, both at home and abroad.

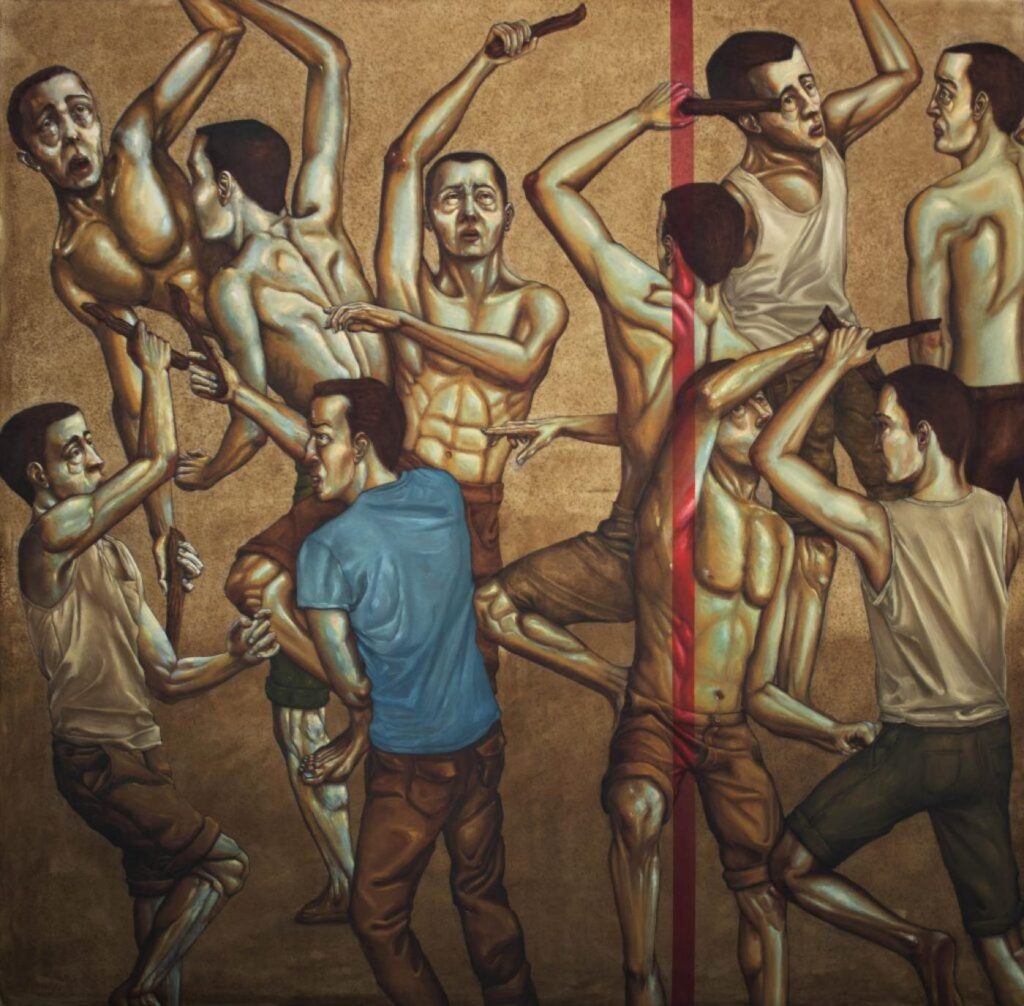

1. Shefa Salem

Benghazi-based Shefa Salem, 25, is a self-taught visual artist, whose paintings focus on socio-political issues, feminism, and research into the history of Libya.

Her 2020 painting Kaska, Dance of War, which is part of her Identity Project on Libyan history, portrays the Libyan Kaska dance, traditionally performed by the Timihu – Amazigh people from the Sahara region living along the Libyan border.

The first depiction of this dance appeared on the walls of Egyptian temples in Deir el-Bahari thousands of years ago, showing soldiers dancing Kaska as they fight with sticks for water.

In Salem’s painting, the dance is part of a presentation on the duality of war, symbolised by a horizontal red line dividing two images designed to be placed in a row. In the top painting the men are fighting, representing cruelty and terrorism, whereas the lower image depicts women subjected to the pain and loss of war.

“I have always been passionate about art,” says Salem, who is currently studying architecture at the University of Benghazi. “In the beginning I was copying images, teaching myself how to tackle realistic work, until in 2018 I started making my original art.

“My work is storytelling and issue-telling, I’m trying to present some of the issues related to Libya as a country. The main issue is of course this endless war, and the uncertainty that comes with it. But just as important is our need of belonging.”

Salem says that it feels that the government is not concerned about the development of the arts in Benghazi. “In Tripoli’s old city, galleries and artist-run spaces are opening and closing, but that’s not the case here. We do have an art department at the university here, but it’s not very well-equipped.”

She now works in a makeshift studio on the roof of her parent’s home, which she calls her “escape from reality”.

“The reality outside is very ugly, so my studio is my safe haven,” she says. “I need room as I like to make big art pieces. I feel that my figurative historical subjects need to be big. You can’t make them small, it doesn’t give you the same effect.”

2. Tewa Barnosa

An artist who left Libya but continues to contribute to the development of its art scene from abroad is 23-year-old Tewa Barnosa, now based in Berlin. In 2015, a year after the outbreak of the civil war in her native country, she founded WaraQ.

Aged 17 at the time, she set up this independent non-profit organisation dedicated to supporting the contemporary Libyan art scene locally and in the diaspora, encouraging dialogue between artists and audiences.

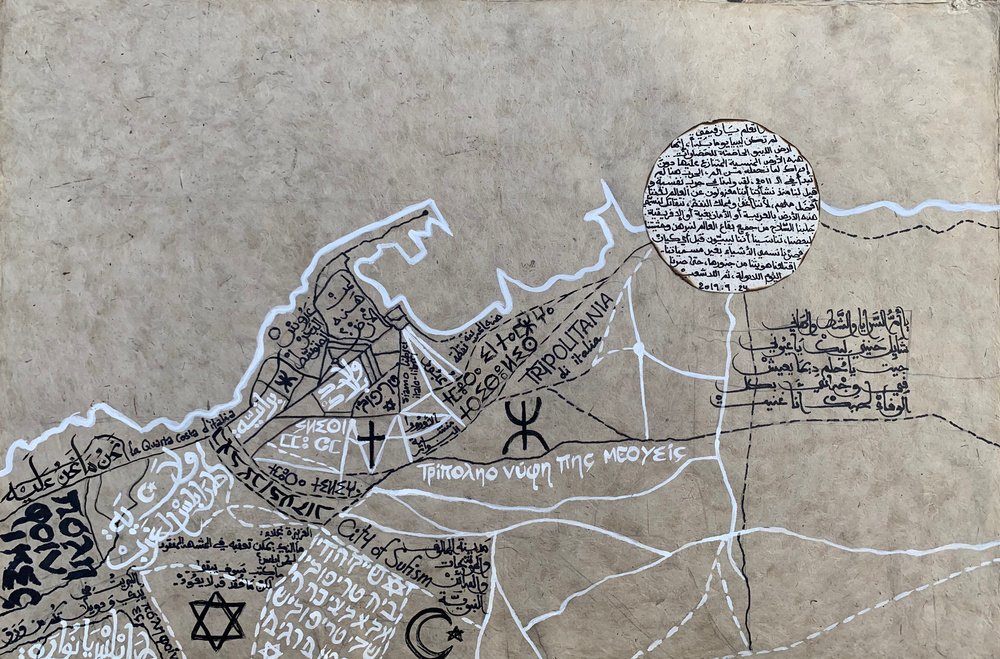

In her work she focuses on denied and erased languages, ancient scripts and etymologies, looking at them in the light of socio-political choices made over the years in the country.

Her body of work is diverse and experimental, ranging from paper-based works, installations, digital mediums, moving images, and, recently, sound. She specialises in themes related to pre-established narratives, which she questions and investigates.

“My research often revolves around the construction and destruction of knowledge, the means and tools used to isolate and dehumanise people and the lands they inhabit,” Barnosa says.

A striking multimedia work of hers is Who are the True Tripolitanians?. The work criticizes the notion of the so-called “true Tripolitanian” and analyses social privilege within Libyan society.

“Growing up in Tripoli, I observed and heard a common topic in social gatherings questioning the identity and originality of people living in the city, discriminating against other citizens because of their roots and the family last name, the tribe, the area they live in and where they come from,” she says.

The maps she recreated show parts of Tripoli landscapes, and the text replaces borders, re-telling social narratives of the places.

“The names of the streets change, landmarks are given different values, written in a fusion of languages,” says Barnosa. “Tamazight, Hebrew, Greek, Ottoman and Italian were languages widely spoken in the city historically, and represents its history, past and future.”

Another impactful work from 2019 is an audio-visual installation called Mitiga Airport. This airport began operating in 2014 after Tripoli’s international airport was burned during the civil war.

Originally built in 1923 as an Italian air force base, Mitiga airport was targeted by Libyan militia during the 2019–20 Western Libya campaign because of its location in the city.

“Growing up in Tripoli, I observed and heard a common topic in social gatherings questioning the identity and originality of people living in the city, discriminating against other citizens because of their roots and the family last name, the tribe, the area they live in and where they come from.”

“The airport never stopped functioning despite being regularly bombed and attacked by missiles,” she says. “Planes have been fully booked for months, and people worked every day to fix the damage to the planes and the runway.”

To Barnosa the story of the airport mirrors everyday life in Tripoli, and raises the question of whether civilians are showing resilience or rather denial towards their living conditions.

There is a sound piece accompanying the installation, which is a recording of heavy bombing and missiles.

3. Mohamed Abumeis

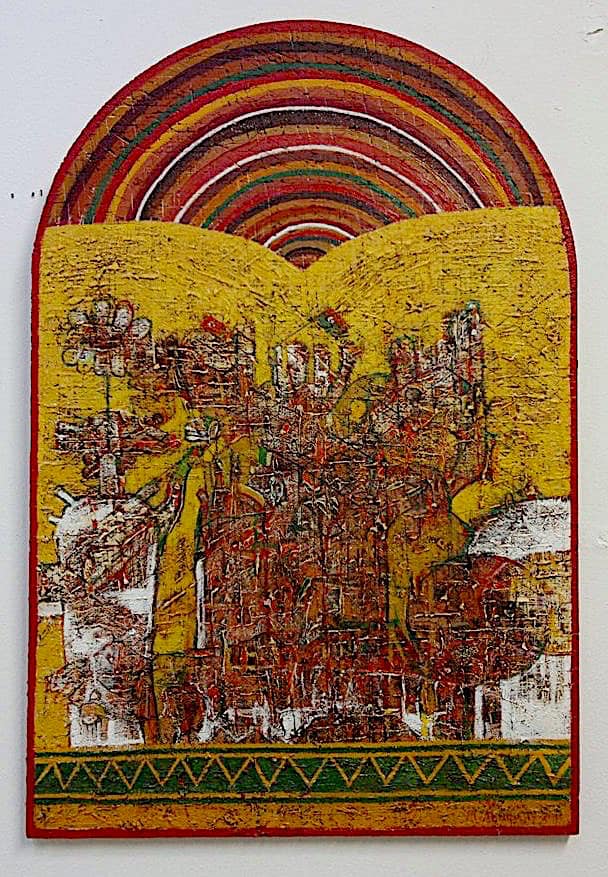

Mohammed Abumies (born 1970) is based in Melbourne, Australia, and his work deeply explores the memory of place and space through painting.

His Libyan identity is central to his canvas art, together with the concepts of hybridity, fluidity, transnationalism, the shifting meaning of “home”, displacement and belonging.

Born in Tripoli, Abumies graduated with a degree in painting and drawing from the Faculty of Fine Art in Tripoli in 1994. His first memories associated with art are from when he was six years old, when he used to draw for his classmates and his teachers in school.

Growing up, he realised that the art scene in Libya was underdeveloped: “The scene was growing up slowly due to the effect of the absolute power that controlled everything in the country,” he says.

“There wasn’t any art community or senior artists to look up to, or even to communicate the value of promoting and growing the Libyan art scene. Today I see more Libyans looking forward to create new political, social and cultural movements for a better future.”

Abumies began exhibiting in 1992, both in Libya and internationally, participating in collective shows in Egypt, Europe, the UK and Australia.

He left Libya thanks to a scholarship from the University of El Fatah, in Tripoli, which enabled him to travel to the UK, before finally settling in Australia years later.

“To my surprise, I didn’t encounter many established Libyan artists who emigrated abroad during the Gaddafi era, or after,” says Abumeis. “The story of exile provokes nostalgia, evoking the actual losses of family, friends, and community which affects both the internal life and the external environment. It’s the loss of a romantic past.”

He developed his style under the influence of Swiss-born German artist Paul Klee’s theory that “colour is the place where our brain and universe come together and meet.” With this in mind, colours became Abumeis’ world: “I feel that I am a fragment of colour, and we have to be as one,” he says.

“The story of exile provokes nostalgia, evoking the actual losses of family, friends, and community which affects both the internal life and the external environment. It’s the loss of a romantic past.”

A piece that the artist is particularly fond of is his painting Liberty Leads Societies from 2011, which he defines as a “revolutionary icon”. The work reflects a tension between his experience of migration and mobility, versus his attachment to his homeland: “It featured what has been called ‘The Arab Spring’ which in Libya was known as ‘The February Revolution’.

“The idea was to use symbols, icons, and signs to represent the Libyan narratives which are continuously unfolding,” he explains.

“I wanted to speak about the Libyan revolution by displaying the colours of the national flag, together with flowers. In terms of technique, I had a textured quality of painting together with the organic indigenous coloration. This for me is a metaphor of seeking liberty, freedom, and change.”

Abumeis is still in touch with artists and art organisations in Libya, and is also undertaking online advisory roles, supporting and mentoring students and artists in Libya: “I develop my art in relation to my multi-layered identity as a Libyan artist passed-in Australia.”

4. Malak Elghuel

Some young Libyan artists, especially those in the diaspora, have never come into contact with the local arts scene. “I wasn’t aware or part of an art community growing up,” says Tripoli-born 25-year-old Malak Elghuel. “I didn’t know any senior artists; I had no one to look up to. I’ve only recently started to learn more and more about Libyan artists and Libyan art in general.”

Now based in Dubai, where she studied at the University of Sharjah’s College of Fine Arts and Design, Elghuel believes that art is a never-ending process of experimenting and pushing herself.

“The subject of all my work is Libya. That’s because it will forever be a huge part of my identity, wherever I go,” she says.

“In many ways, being Libyan and going through all these dramatic shifts in the past couple of years is what gave me this urge to find an outlet to express myself. Art helped me deal with the inner turmoil that comes with being Libyan.”

One of her latest works, If I Could Trace You…If I Could Hear You… is a sound installation based on seven conversations with displaced Libyans. Accompanying it is a poem she wrote along with a video collage detailing the process of realisation of the works.

“The subject of all my work is Libya. That’s because it will forever be a huge part of my identity, wherever I go.”

“Recording events that might be lost with time is important to me, especially in a country that keeps on erasing its own history. It’s so hard to find any archives or an unbiased source of documentation in Libya,” Elghuel says.

To her, the work represents a small act of kindness: “Talking to different people during the interviews gave me a sense of purpose. They all wanted to share their stories. In a way, they felt seen again.”

5. Faiza Ramadan, changing the perception of Libya

Growing up in an artistic household in Tripoli’s countryside with both parents painters, 32-year-old Faiza Ramadan was also deeply influenced by her uncle, Ali Mustafa Ben Ramadan, an art gallerist who was affiliated with the Art House in the early 1990s.

She started creating comic books with her sister based on their life when she was 14-years old.

Although her studies and career were in business and technology, she continued to visit art shows, which were more prevalent before 2011, she says: “Before the revolution Libya was more open to foreigners, and exhibitions were a strong point of interest for expats. Many established artists rose to success during that time.”

In terms of her personal work, her main interest in paintings is portraits and capturing human emotions: “Some of my work is abstract, but I always find myself going back to portrait.”

Her work is a mix of her experience, culture and heritage: “I have a Libyan father and Ghanaian mother, and this has influenced my artwork culturally. You can detect African influences in much of my work.”

One of Ramadan’s strongest symbols of current events is The Meeting (2019), a painting representing Libya’s economic divide.

“This painting is inspired by a scene I saw while I was driving to work, “says Ramadan. “There was a group of elders sitting on the sidewalk in the cold, waiting in turns to withdraw cash from the bank.

“I used that image and I combined it with another scene which we are very familiar with, which is the numerous and countless political and economic meetings. I wanted to create a dystopian effect by this juxtaposition.”

This painting of Cubist reminiscences, realised with mixed media on canvas with letterpress ink, refers to the current Libyan economic and financial situation. This became extremely dire since the Libyan uprising in 2011.

Currently, the country suffers from a lack of cash liquidity, which has led to companies and institutions not being able to pay employees.

A visible consequence is the endless queues in front of banks, as citizens are unable to withdraw money due to the persistent liquidity crisis.

“I suddenly had a lot of free time, and I needed a way to cope with anxiety and uncertainty. After the revolution I created more artworks and decided that this is what I want to do and be.”

It was only during the revolution that Faiza started to devote more time to painting: “I suddenly had a lot of free time, and I needed a way to cope with anxiety and uncertainty. After the revolution I created more artworks and decided that this is what I want to do and be.”

She is now promoting and selling her work through the platform De-Orientalizing Art, as well as participating in exhibitions in Libya and abroad.

In 2018 she also started the Facebook community, Fine Art Libya, to connect art enthusiasts with artists, and nurture a base of potential future collectors to support emerging artists in Libya.

Faiza says she wants people to see Libya as more than a failed state, torn by civil war: “I believe that, in my artwork, I’m representing my own version of Libyan history. Hopefully, by expressing ourselves, we will be able to change the international community’s perceptions of us.”

Source: The Middle East Eye