Articles

Al-Muṣāra: the Marinid royal citadel in Fez

Article author: Iñigo Almela (UNED)

Date of publication of the article: 11/03/2025

Year of publication: 2025

Article theme: Archaeology, Architecture, Arqueología, heritage, History, Marruecos, Morocco, Patrimonio.

The Marinid almunias

Although the studies carried out so far have uncovered numerous almunias built by the leaders of al-Andalus and the Maghreb, the fact is that the Marinid period (13th to 15th centuries) had been rather neglected in this respect. As a result, there remains no Merinid estate that has been preserved in good condition, as is the case with the Agdal in Marrakesh (of Almohad origin) or the Generalife in Granada (Nasrid). Nor are the main chronicles of the time generous in revealing the identity of examples. In fact, the Marinid dynasty has practically no detailed references to palaces and estates in written sources, which is unexpected when compared to its Nasrid parallel.

The aim is to recover the memory of al-Muṣāra [oil mill, in Arabic], an extensive space of solace of the Merinid sultanate in Fez la Nueva.

The almunia al-Muṣāra

The Marinid palatine city was founded on a slightly elevated site overlooking the river and isolated from the old medina of Fez, occupying an upstream location that allowed priority access to the river’s water, thus favouring the supply of the almunia of al-Muṣāra. This estate extended along a gently sloping hillside to the north of New Fez, separated from it by the riverbed and the Fez-Meknès road. As such, the main watercourse ran at the foot of the almunia.

As far as historical sources are concerned, there are some very important references to identify the estate and to situate it chronologically. For his part, Ibn Abī Zarʿ (d. 1326) mentions in Rawḍ al-qirṭās the construction of the great waterwheel in 1286 and the planting of the sheepfold in 1287, these works corresponding to the beginning of the rule of Abū Yaʿqūb Yūsuf (1286-1307), son of the founder of New Fez. Subsequently, Ibn al-Ḫaṭīb (1313-74) provided in al-Iḥāṭa the identity of the engineer who designed the waterwheel, Muḥammad b. ʿAlī b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Muḥammad Ibn al-Ḥaǧǧ, a Mudéjar from Seville who was an expert in mechanics. In fact, he notes that the work was commissioned by Abū Yūsuf Yaʿqūb, which means that al-Muṣāra’s project may have been initially planned by the founder of the palatine city and not by his son, who, in view of the death of his predecessor, could have undertaken the work to a large extent. Both Ibn al-Ḫaṭīb and Ibn Ḫaldūn, who had first-hand knowledge of the place, provide us with information about al-Muṣāra as a place to receive and host Nasrid sultans. One of the most notable constructions was the Qubbat al-ʿArḍ, a pavilion used for the inspection of troops, as well as for receiving or dismissing retinues. Descriptions of the cultivated area are still unknown, although one known qasida highlights its beauty and natural wealth.

Both Ibn al-Ḫaṭīb and Ibn Ḫaldūn, who had first-hand knowledge of the place, provide us with information about al-Muṣāra as a place to receive and host Nasrid sultans.

With regard to the extent of the almunia, the study suggests that the complex may have been bounded to the south by the historic Fez-Meknès road, to the east by an aqueduct and to the north by a topographical change in the slope. Although no remains of a perimeter wall have been found, it is likely that it existed, following the model of other almunias in the Islamic West.

The water supply system: the waterwheel and the aqueduct

As written sources indicate, the water-supply system of the citadel is one of its most notable elements, including a large waterwheel that lifted water from the Fez River and an aqueduct that transported it to the estate. The remains of the waterwheel are located on the northern bank of the river, in front of the north gate of the palatine city (Bāb al-Wādī), and consist of a massive structure built from two large walls separated by a central canal. The walls were built in a stepped pyramid shape with lime rammed earth and then completed with brickwork to create a quadrangular elevation. In this way, the rammed earth supported the weight of the wheel at its highest point and transmitted it to the ground, while the brickwork, lightened with arched openings, formed an upper platform that completely embraced the horizontal diameter of the wheel.

Although its wooden structure has disappeared, traces of the wheel’s rotation are still imprinted on the wall, revealing a diameter of 25 m. This is a dimension unparalleled in the Islamic West for a water wheel. The water wheel was used to lift water from the riverbed to the aqueduct, which had two catchment points at the head of the aqueduct. Firstly, there was the aqueduct’s cistern, located 7.80 m above the axis of the wheel, and secondly, a piezometric turret whose load level was 10.40 m above the axis of the wheel and whose discharge led to a tank built into the aqueduct’s wall to supply water under pressure. This second option would make it possible to reach higher levels or to supply water pumps.

The aqueduct connected the waterwheel to the estate, but only the southern part of the aqueduct has survived for a distance of 170 m, that is, from the waterwheel to its intersection with the Fez-Meknès road. It is precisely this section that is the most monumental, as it is the one with the highest elevation. In turn, its route has two distinct sections, marked by an intermediate turning point where a slight change in trajectory and design can be glimpsed. The first (northern) section is narrower and has small arched openings that do not follow a harmonious rhythm. The second (southern) one starts from the waterwheel with a robust section and is organised around large horseshoe arches and buttresses. It is possible that these are two distinct phases, the second consisting of a transformation of the aqueduct that was necessarily linked to the construction of the great waterwheel. However, it is also possible that these are not widely separated interventions in time, but stages in the construction process that involved the re-staging of the height and reinforcement of the first section.

The al-Muṣāra almunia was a large building, representative of Marinid power and on a par with other state estates in al-Andalus and the Maghreb.

The aqueduct also includes two large octagonal towers flanking its intersection with the Fez-Meknès road, suggesting the existence of a passageway through the aqueduct wall framed by these towers, which create an architectural and defensive language of great presence in the landscape. This section of wall between the towers has completely disappeared and the characteristics of the opening it may have contained are unknown.

As for the interior of the almunia, which could have been more or less rectangular in shape, several pavilions and reservoirs were scattered around it. Since the work of Bressolette and Delarozière, we have archaeological evidence of at least two aulic complexes and a reservoir. The first two are in a state of ruin and have survived to the present day thanks to their location within a cemetery that developed on the site of the almunia in the centuries following its abandonment, while the 55 m long reservoir has disappeared in the last decade as a result of urban expansion.

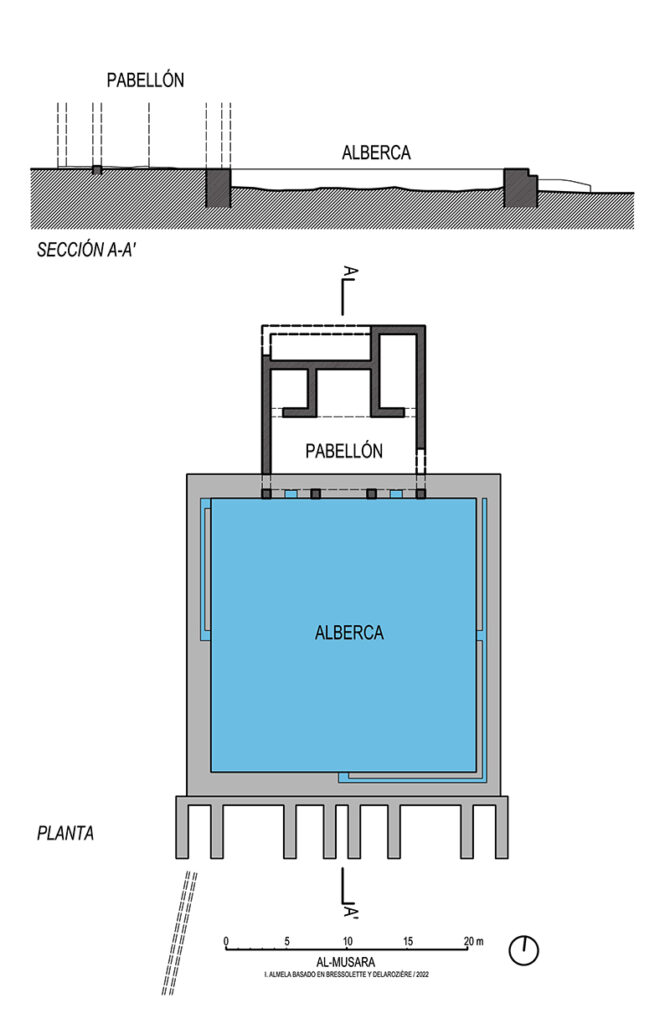

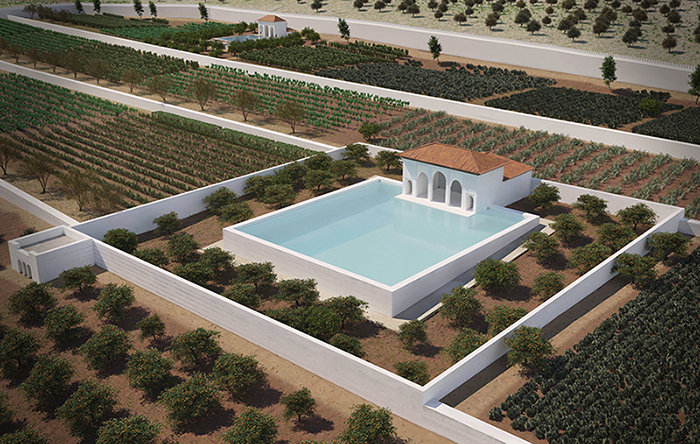

Complex 1 is located on one of the highest points on the estate and consists of a square reservoir measuring 22 m on each side and a porticoed pavilion perched to the north of the reservoir. This pavilion had a T-shaped plan and opened onto the water basin by means of a portico with three openings directly over the wall of the pool. Its design is very reminiscent of the Nasrid palace of the Lower Partal in the Alhambra, where the portico concentrates all the architectural attention and is reflected on the horizontal surface of the water.

Complex 2 uses a similar model to the previous one, although it is larger and has a slightly more complicated design. The basin measures 39 m x 44 m and the pavilion projects partially into the quadrangle described by the pool, creating a levitating effect over the water. The complex also conserves a rammed earth fence that surrounded it and delimited an interior garden around the pool. This solution, which may also have existed in complex 1, isolated the pavilion from the rest of the estate and created a noble space with greater security and privacy. In addition, the species cultivated within this enclosure were probably more exquisite and focused on the delight of the user, while the species present in the rest of the estate would have had a more productive function.

Finally, in one of the corners of complex 2 are the remains of a tower-pavilion built with rammed earth, the interior of which was divided by three brick arcades. This work suggests that it may have had an upper terrace level from which the estate could be observed from a higher level.

In conclusion, the al-Muṣāra almunia was a large building, representative of Marinid power and on a par with other state estates in al-Andalus and the Maghreb. Its interior configuration, although largely unknown, suggests a polynuclear system in which the pavilions were isolated by their own fences, but were at the same time integrated into the estate as a whole. For their part, the residential or recreational buildings maintain a genotype that was widely used in the Islamic West with pavilion-shelters, although they show developed and innovative typologies. Finally, its hydraulic supply system is particularly significant as it has a large-scale construction such as the monumental waterwheel of Fez, a work by a recognised author that shows the important technical development of the time and the building capacity of the Marinid sultan.

This brief article provides a synthesis of the paper ‘The Marinid Royal Estate of Ǧannat Al-Muṣāra and Its Great Noria (New Fez, Morocco)’, which has been published in the Journal of Material Cultures in the Muslim World (2024) by Brill publishers. The paper is available in open access on the official website, from where it can be downloaded free of charge in the following format PDF.

References

[1] Bressolette, H. and Delarozière, J. (1978-1979), ‘El-Mosara jardin royal des Mérinides’, Hespéris Tamuda 18, pp. 51-62; Delarozière, J. and Bressolette, H. (1939), ‘La grande noria et l’aqueduc du vieux méchouar à Fès Jedid’, in IVe Congrès de la Fédération des sociétés savantes d’Afrique de Nord, Rabat, 18-20 avril 1938, Argel, Société historique algérienne, pp. 627-40.