Articles

A tool, not a compromise

Article theme: Human Rights, Religions.

In the Middle East, the religious sphere must now complement the societal one, which is why the work of Religions for Peace is so vital.

The political power play in our world barely reflects the existential needs and realities of people on the edge of an abyss. The historic societies of what used to be known as “Mesopotamia”, today’s Iraq and Iran; and “the Levant” – Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Palestine and Israel, are currently ignored or misrepresented in piecemeal policies and short-term engagement. The needs of our communities are not necessarily related to the outcome of the US elections, to the future of Nato, or to the contentious eastward expansion of the European project. Nor does the alphabet soup of acronyms that passes for today’s engagement with issues spell an end to human suffering: partnership for peace (PfP); Euro-Mediterranean partnership (Euro-Med); organisation for security and cooperation (OSCE) – each new assortment of signatories and priorities seeks to align governments with the concerns of a myopic global security agenda. But shading states on a blind map means little to the region’s masses.

The primary concern for governments and the international community must be the restoration of human dignity in our societies. This can only be done by applying just law and by stifling voracious interest groups on all sides. Interference and intimidation for political, ideological and financial gain has all but destroyed the fabric of communal harmony that has existed in our region for centuries. The hatred industry has prospered in recent years, fuelled by religious fanaticism, while the grizzly collateral for engagement with the voiceless poor is the lives of suicidal nihilists.

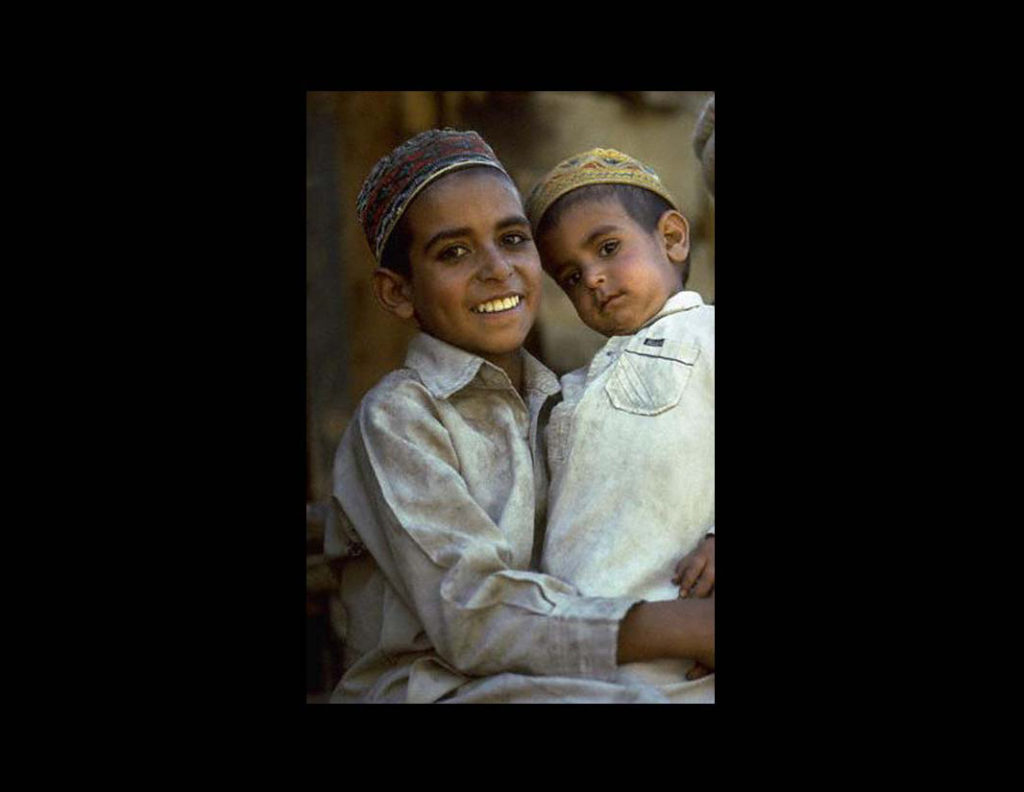

And still, the corrosion of structure and sanity continues. In Iraq, successive wars have left 3 million widows and 2 million orphans to transmit the trauma and bitterness of loss and suffering to future generations. More than 60% of the population are women, while over 4 million Iraqis are internally displaced persons, refugees in their own country.

Our governments and yours refuse to grant our people the rights and recognition of citizenship. Corruption, cronyism and greed define processes at all levels. The recent introduction of opium culture into Iraq is but the latest example of a corrupt response to self-serving overtures – cheap, imported crops from the food bowls of the west have all but put Iraq’s farmers out of business.

Justice, freedom and luxury

To use the classical vernacular from which western democracy claims descent, the Homeric definition of the objectives of communal life seems just as appropriate today: “justice, freedom and luxury.” His words are a useful shorthand for the quality of life that we all seek. In the context of the Middle East, these goals imply a recognition of the historic self-reliance of the peoples of this region. Self-reliance and self-determination are terms that prevailed in the 1920s, post-Versailles era, when the imposed covenants establishing the nations of the Levant and Mesopotamia attempted to re-establish a status quo. How easy it is to forget that at this time the peoples of all three monotheistic faiths lived together in interwoven communities. The politicisation and degradation of our religious hierarchies and our holy cities has created a vacuum for those who prosper on bigotry and intolerance. Today, altruism and charity have disappeared from public policy. The principle of Zakat, one of the five pillars of Islam, which obliges Muslims to invest a portion of their wealth in building a future for the poor, has been toppled by the modern nation state and no replacement institutions have been erected.

The fact remains that in our Middle Eastern context, the religious sphere must complement the societal one. Unless this dangerous imbalance is recognised and addressed in appropriate terms, the pulpit bashers and self-canonisers who capture the attention of desperate and lost souls will continue to misrepresent our history, our faiths and our needs. We are all complicit in empowering the haters as long as we acquiesce to the cry that “the enemy of my enemy is my friend”. Our people and our societies are more complex than two-dimensional representations of allies of “the west” and friends of the “axis of evil”.

To promote true societal self-reliance we must move beyond mere religious platitudes and speak of rebuilding effective religious institutions. At six successive meetings of Iraqi religious leaders, convened by the World Conference of Religions for Peace, we sat with Sunni, Shia and Christian religious leaders who agreed with our call. No one seems to be responsible for the assets of the Iraqi people, funds which have not been deployed to rebuild hospitals, schools and homes, much less Muslim places of worship, both Sunni and Shia, and Christian churches.

Paul Volcker, former chairman of the Federal Reserve, once called for a Middle East development bank to empower the poor through infrastructure development and policy change. Perhaps we should go further still and develop a non-denominational peace corps of architects, engineers and builders to help reconstruct the ravaged nations of our region.

Security framework agreements cannot provide an answer to our problems. Our region is not a military conundrum – it is a dying set of organic and co-dependent communities that have thrived through most of the last three millennia. At this critical juncture in our history, I implore those who endlessly discuss the state of the world to voice “truths” based on empirical fact and sound analysis. The only honourable way to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is to insist that our cradle of civilisation should impose and be subjected to the highest standards in order to revive and empower a system of values and beliefs that transcend pernicious parochial constructs.

“If the universe is non-ethical by our present standards, we must reconsider those standards and reconstruct our ethics.”

By Prince Hassan bin Talal

Princeton, February 6, 2008