Articles

Isabelle Eberhardt, writer, nomad and feminist

Rather than perpetuate the romanticised image of the Orient commonplace in 19th century literature, writer and nomad Isabelle Eberhardt traversed and explored the Maghreb with a critical eye. She not only condemned French colonialism, but also the established gender roles of her era.

The life, views, and literary work of Isabelle Eberhardt (1877-1904) really ought to receive more attention. And not only when examining 19th century Western perspectives on the Orient, which, then as now, were dominated by reports from male travelers. Her life and work provide vital insights into feminist positions and discussions on gender roles at the time.

The life, views, and literary work of Isabelle Eberhardt (1877-1904) really ought to receive more attention. And not only when examining 19th century Western perspectives on the Orient, which, then as now, were dominated by reports from male travelers. Her life and work provide vital insights into feminist positions and discussions on gender roles at the time.

Even though she left behind journals and a wealth of handwritten notes, a great deal about her personal life remains shrouded in mystery. It is known that she was born in Geneva in 1877, the fifth child to a Russian mother, while the name of her father continues to be the subject of speculation.

She was inspired by the Russian feminist and travel writer Lydia Pachkov as well as the novelist Pierre Loti, whom she declared throughout her life to be her literary role model.

Even though she left behind journals and a wealth of handwritten notes, a great deal about her personal life remains shrouded in mystery.

In 1895, when she was only 18 years old, Eberhardt published “Infernalia”, her first short story, under the pseudonym Nicolas Podolinsky. Two years later, she travelled with her mother to Algeria, where she henceforth would refer herself as Si Mahmoud Essadi. After the death of her mother, she relocated the focal point of her life to Algeria and later even spoke of her Maghreb homeland.

A feminist voice rejecting colonialism

Her accounts from the Maghreb stand in stark contrast to the then prevalent romanticized style of writing about the Orient favored by literary figures and travelers alike. Eberhardt regarded the world through which she moved with a critical eye, took a stand on controversial topics and condemned French colonialism, conveying her resentment of established gender roles through her literary protagonists.

Her accounts from the Maghreb stand in stark contrast to the then prevalent romanticized style of writing about the Orient favored by literary figures and travelers alike.

She often placed female characters in controversial and, for that time, extremely objectionable roles. The decision of her fictive character Achoura to sell her body for money is not one that Eberhard found surprising, but rather fully comprehensible, since it remained the only escape for women who did not want to be trapped in a secluded world of marriage.

In a letter, she wrote to her husband Saliman, “Yes, I am a woman before God and Islam. But I am no typical Fatma or ordinary Aicha. I am also your brother Mahmoud, a prominent djilani (of the Sufi Order), and a servant of God, far more so than as a servant of my husband, as is every Arab woman according to the Sharia (Islamic law).”

Against a world where gender roles are specified

With her unmistakable and, for that time, extremely courageous dress style, she demonstrated for all to see her demand that individuals should not be reduced to their gender roles. Eberhardt consistently wore a burnus – the typical garment of North African men – and circumvented the prescribed subservient role model for women.

Her provocative appearance also compelled those around her to examine and question conventional gender roles, and, last but not least, to assess the political meaning, purpose, and use of societal norms in the truest sense of the word. Eberhardt refused to comply with what was expected of her and led her life accordingly.

She repeatedly undertook lengthy journeys through Tunisia, Morocco, and Algeria – either alone and on foot, or in the company of a caravan. She noted:

“I will remain a nomad for the rest of my life, seduced by the ever-changing horizon and the prospect of distant locations yet to be discovered, as every journey, even to the most overcrowded and most visited lands, is a revelation.”

Free from constraints

This nomadic existence freed the writer from any constraints. She noted in her journal that it was only here, outside her comfort zone, that she could experience “real freedom”.

Her manner and appearance often met with strong disapproval. It simply wasnʹt accepted for a woman to frequent coffee houses, smoke and drink alcohol. Neither did her era sanction a woman who presented herself as a man who animatedly discussed politics and role models.

Isabelle Eberhardt was not only on a quest to find herself. She was also deeply impressed by spirituality, the rejection of consumption, and the motivation to change things. Through her literary production, she attempted to draw a different possible image of reality – a world in which men and women were not primarily those roles assigned to men and women, but individuals who did not have to conform to pre-determined conventions.

Through her affiliation with the Qadiriyya Sufi order, she supported those in need and championed demonstrations against the French colonial regime, which would frequently end in violence.

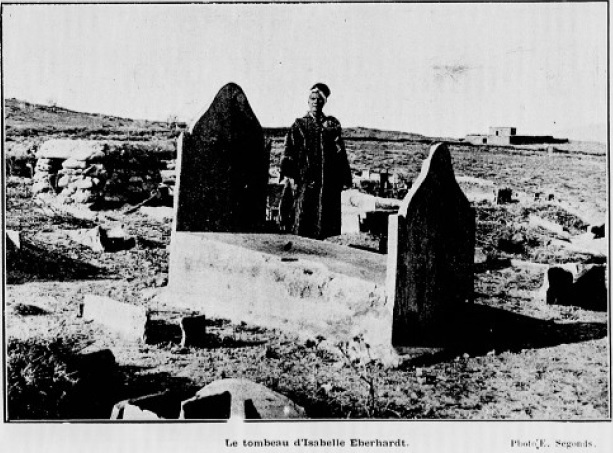

Isabelle Eberhardt died in 1904 at the age of 27 during a flash flood in Ain Sefra in the Algerian province of Naama.

Source: Qantara