Articles

Working for peace: dark hope

Article theme: Human Rights.

A Moral Witness to the ‘Intricate Machine’

“I am an Israeli. I live in Jerusalem. I have a story, not yet finished, to tell.” This is the opening line of David Shulman’s powerful and memorable book, Dark Hope, a diary of four years of political activity in Israel and the Palestinian territories. It is a record of the author’s intense involvement with a volunteer organization composed of Israeli Palestinians and Israeli Jews, called Ta’ayush, an Arabic term for “living together” or “life in common.” The group was founded in October 2000, soon after the start of the second Palestinian intifada.

“Israel, like any society, has violent, sociopathic elements. What is unusual about the last four decades in Israel is that many destructive individuals have found a haven, complete with ideological legitimation, within the settlement enterprise. Here, in places like Chavat Maon, Itamar, Tapuach, and Hebron, they have, in effect, unfettered freedom to terrorize the local Palestinian population; to attack, shoot, injure, sometimes kill—all in the name of the alleged sanctity of the land and of the Jews’ exclusive right to it.

“Shulman’s diary, however, gives an acute sense of the gap between peace schemes in their “peace process” phase and the relentless and dreadful reality on the ground. The reality is shaped not by agreements but mainly by the violent workings of Israel’s intricate machine and by the violence of Palestinian forces.

“The diary gives us only a glimpse of some of the visible workings of the intricate machine. But I believe that understanding what is going on in the South Hebron Hills, a tiny part of the conflict, can free us from misconceptions about how the intricate machine works. There are relatively few settlers around Hebron and far fewer in the outposts that have been set up there. Their number is not about to get dramatically larger. Nonetheless, the official Israeli machinery is inexorably having its effect—it controls the land and gets rid of the Palestinians living on it by making their lives intolerable. The intricate machine does not depend on the number of settlers. It depends far more on the ways the roads to the settlements and the outposts are planned, built, and protected by the Israeli forces.

“Shulman starts with an impersonal account describing what happened on April 2, 2005, near a settlement south of the Hebron Hills where the Palestinians lived in caves and kept flocks of sheep and goats:

“It began some two weeks ago when Palestinians from [the village of] Twaneh noticed a settler—almost certainly from Chavat Maon, the most virulent of the settlements in the area—walking deliberately through their fields in the early morning. Shortly afterward the animals got sick and the first sheep died. Then the shepherds found the poison scattered over the hills, tiny blue-green pellets of barley coated with… deadly rat poison from the fluoroacetate family…. The aim was clear: to kill the herds of goats and sheep, the backbone of the cave dwellers’ subsistence economy in this harsh terrain, and thus to force them off the land.

“What we are fighting in the South Hebron Hills is pure, rarefied, unadulterated, unreasoning, uncontainable human evil”.

Nothing but malice drives this campaign to uproot the few thousand cave dwellers with their babies and lambs. They have hurt nobody. They were never a security threat. They led peaceful, if somewhat impoverished lives until the settlers came. Since then, there has been no peace. They are tormented, terrified, incredulous. As am I.

“Shulman shows that the settlers are supported by what he calls the “intricate machine,” a term he uses to describe various Israeli government agencies, including the army, the police, and the civil authorities that administer the West Bank. But the relations among the various agencies can be so intricate that it is no longer clear who is in charge of a particular policy or action. Hagai Allon, an Israeli official appointed by the former defense minister to be in charge of “the social fabric” in the territories, stated that the army does not comply with the defense minister’s orders. Referring specifically to the Hebron Hills area, Allon said the army acts “in the service” of the settlers. It carries out, he said, “an apartheid policy,” establishing facts on the ground that are meant to make evacuation of settlers of the West Bank impossible.

“In short, Shulman shows that a wild generation was born in the territories, a generation whose members are far bolder than their parents, far more ready to defy the law, and far more capable of utter lawlessness with regard to Palestinians. It is a generation saturated with intense hostility toward the Arabs, and ferociously tribalistic.

“In the South Hebron Hills, there is now a place aptly called “Lucifer’s Farm.”

Its “owner,” Yaakov Talia, is an Afrikaner who converted to Judaism at the end of apartheid in South Africa. He is another wild, charismatic tough guy who attracts many religious young people. They spend time on his farm helping to take over more and more land.

The intricate machine

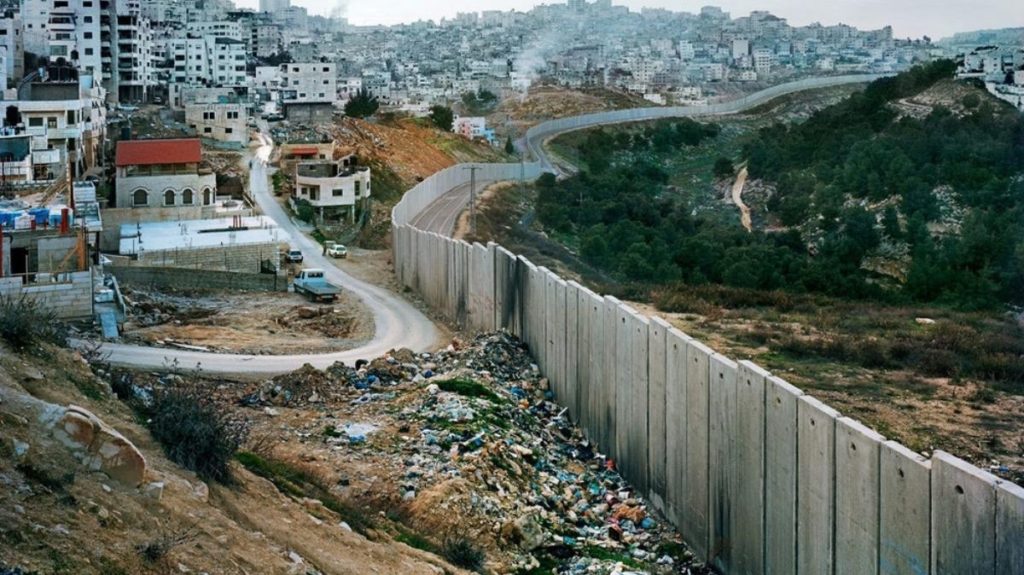

“The diary gives us only a glimpse of some of the visible workings of the intricate machine. But I believe that understanding what is going on in the South Hebron Hills, a tiny part of the conflict, can free us from misconceptions about how the intricate machine works. There are relatively few settlers around Hebron and far fewer in the outposts that have been set up there. Their number is not about to get dramatically larger. Nonetheless, the official Israeli machinery is inexorably having its effect—it controls the land and gets rid of the Palestinians living on it by making their lives intolerable. The intricate machine does not depend on the number of settlers. It depends far more on the ways the roads to the settlements and the outposts are planned, built, and protected by the Israeli forces.

“In fact, many of the outposts in the West Bank are little more than Potemkin villages, but this, too, is almost irrelevant, since the roads leading to them are roads that, according to official doctrine, need to be protected constantly, in order to ensure the safety of the inhabitants even if they consist of only one or two families. The fewer the number of settlers, the more vulnerable they are, and so they need heavier protection. Protecting a road means preventing the Palestinians from getting near both sides of it and regulating their movement by means of barriers on the roads they are allowed to use. There are 539 barriers to movement in the West Bank, eighty-six of which are manned checkpoints.

“So the roads are the method by which the West Bank is fragmented, with almost no mobility for the Arabs locked in their enclaves”. In addition to this, every settlement and every outpost is surrounded by a safety zone called a “special security area.” So the expansion of Israeli control of the West Bank is not determined by the number of settlers but by the extent of the zone of protection, from which Palestinians are excluded.

“Here is how it works. First, a settlement is established with a designated area for future development and a wide zone of protection. Then satellite outposts are erected in the hills on the outskirts of the settlement. The outposts enlarge the area to be protected and especially the roads leading to the outposts. The commentators who emphasize the growth of the number of settlers in the West Bank miss the intricacy of the machine. Population growth is not the main factor. In fact, the main growth in population in recent years has been in four ultra-“orthodox towns that are not far from the Green Line. The population in these four towns now amounts to nearly one third of the settlers in the West Bank. Clearly more important than the increase of settlers is the increase in the number of outposts and their interconnecting roads.

“The intricate machine works relentlessly—it hardly matters which group is in power. Center- and Labor-based governments believe that it is too much of a political and military hassle to dismantle the settlements one by one. They say that one day these settlements will be dealt with on a wholesale basis—the way Sharon dealt with the Gaza Strip settlements, which were all evacuated at the same time. Likud-based governments, by contrast, are against removing the settlements in any case. All governments of Israel have also shared the view that all the settlers—authorized as well as unauthorized—should be protected by the army. Benefiting from these shared views, the intricate machine works no matter who is in power.

“No one among the Palestinians is going to believe in a grand scheme for a final settlement as long as their lives are so degraded”.

Hamas has declared itself, as a matter of principle, against a large-scale scheme for a peaceful settlement with Israel; but the issue that must be faced is the utter mistrust of large-scale schemes on the part of Palestinians who are not followers of Hamas and want to lead peaceful lives. To narrow the gap between the grand schemes and the reality on the ground, the intricate machine must be halted. Daily life has to be seriously improved if any grand scheme is to be trusted. To believe that this is going to happen, however, calls for a leap of faith—the sort of faith, perhaps, that keeps a man like David Shulman trying to help Palestinians, even while he distrusts grand schemes.

By Avishai Margalit, is Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He is currently the George Kennan Professor at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. He has just been awarded the 2007 Emet Prize by Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert for his work in political thought, ethics, and philosophy. (December 2007).

Dark Hope: Working for Peace in Israel and Palestine, by David Shulman. University of Chicago Press.

November 7, 2007