Articles

Decalogue of good practices for the dissemination of Islamic heritage

Date of publication of the article: 06/09/2022

Year of publication: 2022

Article theme: Activities, Archaeology, Architecture, History, Patrimonio.

Last May 2022, the Islamic Culture Foundation organized the workshop “Islamic Heritage: good practices for its dissemination”. The 3-days workshop, taught by different specialists in heritage management, such as Rafael Martínez (journalist and heritage interpreter), Felipe Vidales (historian and official guide in Toledo) or Irene Suárez (FUNCI’s activities coordinator), aimed to offer tools for the interpretation and management of Islamic heritage from a social perspective.

As part of the workshop, FUNCI developed a Decalogue of good practices for the dissemination of Islamic heritage. This decalogue compiles the recommendations and advice issued during the workshop, taking into account the different concerns of the participants (most of them professionals in the field of heritage management and dissemination) and the areas in which they have encountered the greatest difficulties. The aim of this Decalogue is to promote an exercise in heritage management, recovery and interpretation that generates inclusive narratives, encapsulating without prejudice or preconceptions the intercultural and interreligious character that has characterized the history of Spain.

Why a social dimension of heritage?

Heritage is a source of memory, understanding, identity, cohesion and creativity[1]. Its existence, present and past, comprises the principles and ideals shared by a society, reflecting the development and conflicts on which it has been built, and the different elements, influences and set of values that are common to it. This is extremely important, as it reflects the complexity of a society’s identity, which is built on multiple influences and interweaves the different civilizations and peoples on whose legacy it has developed.

From this perspective, the recovery of heritage helps to reinforce collective identity and foster social cohesion. Building on this definition, recovering heritage implies accepting the different civilizations and histories on which a society has been built, recognizing their distinct cultural traits and the expressions of political and social organization that have ultimately resulted in (and helped shape) today’s societies.

This is especially relevant in the case of Spain, where we find a complex process of construction of national identity, which has its roots in the period of the so-called “Reconquest”, which culminated at the end of the 15th century with the victory over the last Islamic kingdom of the Iberian Peninsula. The adoption of this historical moment as a reference point for the country’s identity has had important consequences on the conception of our national identity, loading it with a strong Catholic imprint, and, above all, formulating it through a process of identity construction antagonistic to Islam. The latter is understood as a foreign and opposed element, both culturally and religiously, and approached from a conflictual perspective.

This process acquires special relevance when we speak of heritage, since its interpretation has been translated into an exclusionary projection towards the past, which suppresses the “mixed history” of the Iberian Peninsula and ignores or limits the impact that the Islamic civilization had on it from the 8th century onwards[2].

This process of identity construction not only affects our understanding and acceptance of history, but also the interpretation and valorization of our heritage. The projection of values (and power relations) on a society is produced through different key elements, material and immaterial, that contribute to build the collective imaginary. In this process, the public authorities construct their narrative through different emblematic monuments and legacies[3], which contribute to transmitting the system of values with which they want to be identified, giving special relevance to certain heritage elements in the process, and actively excluding those that do not fit in with the historical and identity discourse constructed. In Spain, this is especially notable in the case of Madrid, whose Islamic origin and the heritage not only have been eliminated over the centuries, but are actively hidden due to the difficult fit they have with the official national narrative.

Thus, the adoption of a strongly Catholic and nationalist influenced narrative has historically generated an exclusionary discourse that finds in Islam its main antagonistic element, contributing to the exclusion of Muslims from the current national conception. The use of heritage contributes to reinforce this narrative of exclusion. This narrative and use of heritage feeds the Islamophobia that we at the Islamic Culture Foundation are trying to dismantle.

This is where the social approach to heritage management and recovery becomes particularly important. The recovery and dissemination of Islamic heritage contributes to question the reductionist narratives that exclude the period of Al-Andalus from the official national history and identity. In FUNCI, we consider that its recovery and correct treatment, through an objective analysis and free of prejudices or preconceptions, contributes to promote social cohesion, through the acceptance of a complex historical past and subject to varied influences, which recognizes the mixed, interreligious and intercultural nature of identity, of which Islam is a fundamental part.

How is this social purpose transmitted?

The difficulty, then, lies in how to adopt that social purpose, which must be intrinsic to our work of heritage recovery, management and interpretation. This task involves breaking with many of the accepted historical preconceptions, at the risk of wounding sensibilities and constantly challenging the knowledge of heritage interpreters.

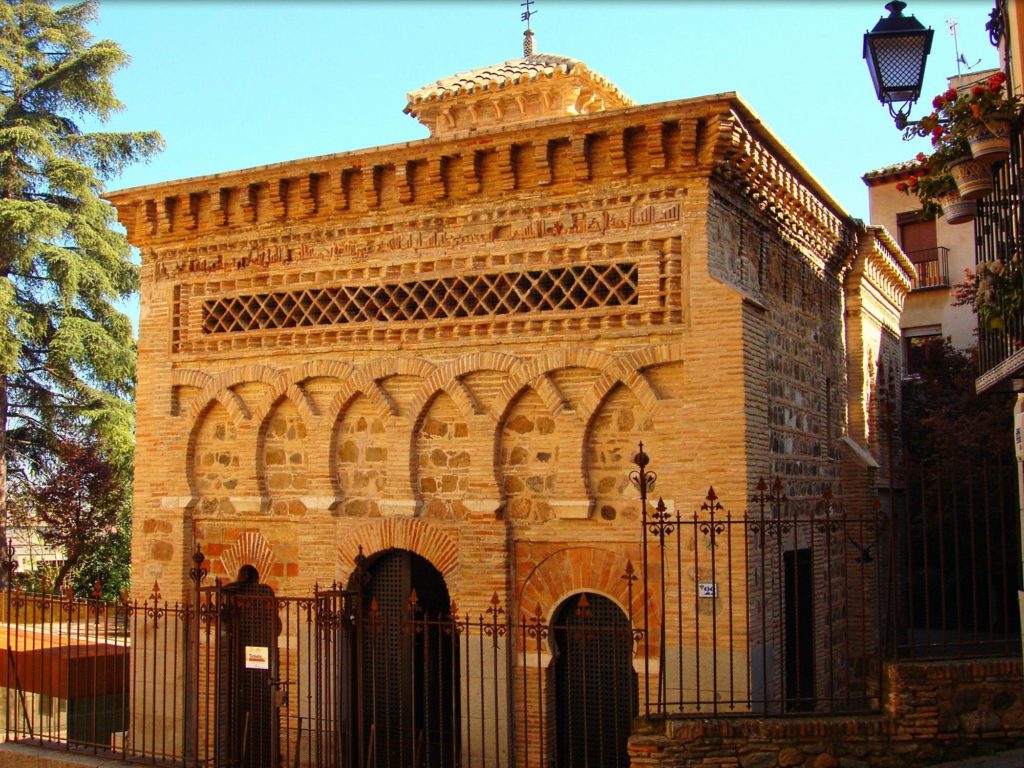

Answering the question that introduces this section is, precisely, the objective of the workshop given by FUNCI. Based on the experiences of Toledo and Madrid, and the work carried out through the Center for Studies on Islamic Madrid (CEMI) and the Center for Studies on Islamic Toledo (CETI), the speakers explored the difficulties of working with Islamic heritage, the multiple ways in which it reflects the identity and social reality of the moment, and the objectives and tools that can be used to contribute to the development of an inclusive historical narrative that fosters social cohesion.

The main outcomes of the workshop have been encapsulated in the following Decalogue of good practices for the dissemination of Islamic heritage, which we hope will serve as a tool and aid for all guides and heritage experts working on the country’s Islamic legacy.

These good practices include:

- Taking care of the language.

- Avoiding the orientalization and foreignization of Al-Andalus.

- Relying on a clear definition of basic concepts.

- Always cite the sources.

- Generate inclusive narratives.

- Deconstruct myths and legends.

- Generate emotions and search for the visual heritage that sustains the historical interpretations transmitted.

- Adapt the professional’s discourse to the type of audience.

- Promote discussion.

References

[1] Convenio marco del Consejo de Europa sobre el valor del patrimonio cultural para la sociedad, 27 de octubre de 2005.

[2] Molinos Gordo, Asunción y Pacheco González, Andrea (2022). “Movilizar la historia como pedagogía de la alteridad. Entrevista a Daniel Gil-Benumeya”, Sombras ocultas en el tiempo. Madrid: Felipa Manuela Ediciones

[3] Castro Fernández, Belén; López Facal, Ramón. «De patrimonio nacional a patrimonio emocional». Her&Mus. Heritage & Museography, 2017, Vol. 18, pp. 41-53, https://raco.cat/index.php/Hermus/article/view/338101.