Articles

Cervantes and Islam

The life of Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra unfolded during a time of profound change and conflict that shaped Europe and Spain in particular. The 16th century and the early 17th century witnessed religious wars across the Mediterranean, the Reformation and Counter-Reformation within the Christian world, and the far-reaching impact of the discovery of the New World. Cervantes’s own journey mirrored these turbulent times, marked by triumphs, fears, and tragedies. One important aspect of his work is his familiarity with Islam and the way it is reflected in such seminal works as Don Quixote.

Islam as a Historical and Cultural Rival

Since its emergence in the 7th century, Islam had posed a continual challenge to Europe. Its rapid expansion led to the creation of a vast territory that solidified during the 8th and 9th centuries, making it not only a religious rival to the Christian states, but also a political, economic, and cultural one. Much of medieval Christian literature regarded Islam as a heresy or a distorted offshoot of Christianity, viewing it as the most dangerous of religious systems. This negative image was echoed in literary works such as Dante’s Divine Comedy, where the Prophet Muhammad is punished in hell. In the poem, the Italian author “reproaches Islam’s final prophet for having broken religious unity”.

Coexistence and Conflict in the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula was a unique region due to the coexistence of Muslims, Jews, and Christians during the Middle Ages. Although the Christian conquest concluded in 1492 with the capture of Granada, the history of Islam in Spain did not end there. After 1492, many Moriscos (Muslims who were forced to convert whether in name or in earnest to Christianity) remained in Spain. Despite initial promises of tolerance, efforts were soon made to enforce rapid and genuine Christianization, leading to widespread intolerance and repeated uprisings throughout the 16th century. Philip II banned the use of the Arabic language, as well as Morisco names, clothing, and customs including bathing practices and traditional celebrations. This repression sparked the Alpujarras Rebellion in 1568, which was brutally crushed by 1570, resulting in the forced migration of thousands of Moriscos from Andalusia.

“Wherever we are we weep for Spain ; for, in short, here were weborn, this is our native country, and we nowhere find the reception our misfortune requires. Even in Barbary, and every other part of Africa, where we might expect to be received and cherished, we are there most neglected and misused. We knew not our happiness till we lost it; and so intense is the desire almost all of us have to return to Spain, that most of those—and they are many—who can speak the language like myself, forsake their wives and children and steal back again from exile, unable to conquer their predilection, and knowing now, by experience, the truth of that common saying, sweet is to every man his native land”.

— Don Quixote de la Mancha, Part II, Chapter LIV.

At the beginning of the reign of Philip III, the Moriscos were portrayed as the greatest threat to the unity of Spain. Although religious reasons were cited as justification, the underlying motives behind the 1609 expulsion were primarily economic and political; they were seen as “enemies of the nation” who endangered religious orthodoxy.

The Mediterranean and Cervantes’s Experience

In the 16th century, the Mediterranean was the primary zone of contact—and conflict—between Christians and Muslims. The Ottoman Turkish army was seen as the greatest enemy; the word “Muslim” became synonymous with “Turk” and “barbarian.” In fact, there was a marked intensification of anti-Turkish propaganda in Spain and other Christian states. Battles such as Lepanto (1571) and Tunis (1574) carried more propagandistic than military weight.

Piracy and privateering were also key features of the time, regarded as substitutes for large-scale wars and accepted as a form of “economic” activity. These practices were not tied to any single religion or nation: both Christian and Muslim pirates operated across the Mediterranean in roughly equal numbers. Cities on both sides—such as Algiers in North Africa, and La Valetta, Naples, Almería, and Valencia in Europe—supported these activities. By the 16th century, Algiers had become the capital of Mediterranean piracy.

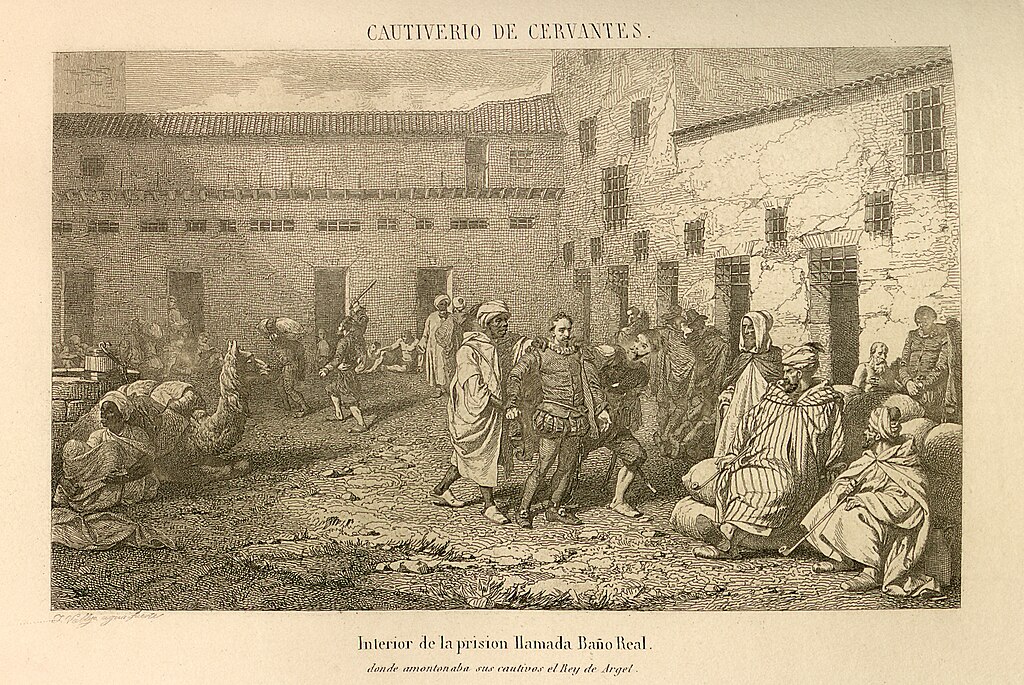

Cervantes had direct, personal experience with Islam and the Muslim world: he fought in naval battles against the Turks, including the famous Battle of Lepanto, and was held captive in Algiers from 1575 to 1580. This formative experience profoundly influenced him and is reflected throughout many of his works.

Cervantes: A Borderland Man

Literary historians often refer to Cervantes as a “borderland man” because he had firsthand knowledge of both cultures and acted as a mediator, building bridges between them. His literary works transform historical time into literary time, grounded in his personal experiences—especially those in the western Mediterranean.

Although he was physically freed in 1580, Cervantes continued to revisit his experiences of captivity and combat throughout his life. Dramas such as The Deals of Algiers (Los tratos de Argel) and The Prisons of Algiers (Los baños de Argel) are considered testimonial literary creations. Through these plays, he aimed to raise awareness about the plight of captives, but also to encourage political dialogue between Christians and Muslims. His knowledge of piracy likewise features in other works, such as The Illustrious Kitchen Maid (La ilustre fregona) and The Generous Lover (El amante liberal).

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Cervantes did not portray Islam or its followers in a simplistic or stereotypical way. His extensive experience with Muslims—both in Spain and in Algiers—prevented him from creating a single, fixed prototype. Despite the intense official propaganda of the time, he was able to offer a nuanced and complex depiction of the Islamic world and the Moriscos. Cervantes did not fully support the persecution of the Moriscos and openly criticized and mocked the obsession with “purity of blood”. His true message regarding Islam was often conveyed cautiously or subtly to avoid running afoul of censorship.

Islam in Don Quixote

In Don Quixote, we find numerous allusions to Islam, although the religion itself is rarely mentioned directly. The most prominent figure is Cide Hamete Benengeli, the fictional Arab and Manchegan historian who is presented as the supposed source of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza’s adventures. This narrative device, introduced in Chapter IX of the first volume, has surprised many readers and sparked much scholarly debate. It is now considered one of the most inventive and thrilling literary recreations of the very act of writing itself.

Cide Hamete is described with positive attributes such as “wise,” “attentive,” and “very curious and precise”. However, Cervantes also occasionally ridicules him, hinting at the stereotype that Arabs might be deceitful. Cide Hamete’s role becomes more consistent and reflective in the second part of the novel. Some scholars draw a connection between the figure of Benengeli and the situation of the Spanish Moriscos, as well as the so-called “Lead Books” of Granada, Morisco forgeries intended to bolster their case against the threat of expulsion.

Other Turkish, Arab, and Morisco characters also appear in the novel, often as storytellers or conveyors of narratives. While some of them are ascribed negative traits commonly associated with the term “Moor” (such as cowardice, deceit, or sorcery) he characters and contexts frequently subvert or neutralize these anti-Muslim tropes. This reflects Cervantes’s tolerant perspective and his desire for peaceful coexistence between cultures.

The novel references long-standing Christian-Muslim conflicts. When it came to matters of faith, Cervantes believed that one must act with prudence, and that true conviction could only arise through understanding the thoughts and principles of the other side. Particularly meaningful are the stories of lovers separated by differences of origin and religion. Cervantes highlights the injustice of such separation, defending the idea that love is determined by the heart, not by external conditions such as wealth, lineage, or “pure blood” a clear contrast to the prevailing politics and propaganda of his time.

The story of Zoraida (María), who leaves her homeland for the sake of love and faith, stands as a powerful example of this theme.

“I have seen many Christians from this window, and none has looked like a gentleman but yourself. I am young, and beautiful, and have a great deal of money to carry away with me. Try, if you can find out how we may escape, and you shall be my husband in the Christian country, if you please; and if not, I shall not care, for Lela Marien will provide me a husband”.

— Don Quixote de la Mancha, Part I, Chapter XL.

The story of Ricote and his family is perhaps the most poignant representation of the persecution and desperate plight of the Spanish Moriscos, closely tied to the 1609 expulsion decree. Through the monologue of Ana Félix, a Morisco Christian woman, the forced exile and the injustice of doubting her true Christianity are vividly portrayed. Ricote’s ironic remarks about Philip III’s policies reflect Cervantes’s criticism of the inhumane decisions made by the Spanish authorities and the Inquisition. Cervantes condemns the spiritual terror and racial persecution endorsed by the clergy. As Emilio Sola points out, Cervantes uses Ricote’s speeches to parody the official rhetoric that justified this cruel expulsion.

“I was born of parents belonging to that nation, more unfortunate than wise, so lately overwhelmed by a sea of troubles. In the current of their distress, I was born away by two of my uncles into Barbary, it availing me nothing to affirm that I was a Christian, as I am; not in word and appearance only, but in deed and in truth”.

— Don Quixote de la Mancha, Part II, Chapter LXIII.“You well know, oh Sancho, my neighbour and friend, how the proclamation and edict which his majesty commanded to be published against those of my nation resident in Spain, struck us all with terror and consternation; at least I was so alarmed myself that methought the rigour of the penalty was already executed upon me and my children before the time limited for our departure. […] In short, we were justly punished with the sentence of banishment—a soft and mild one in the opinion of some, but to the honestly disposed de most terrible that could be inflicted”.

— Don Quixote de la Mancha, Part II, Chapter LIV.

Interpretations and Legacy

Cervantes’s thoughts on Islam have attracted the attention of Muslim scholars, especially those eager to move beyond stereotypes. They see in Cervantes a writer who rose above political propaganda, taking a clear stance in favor of freedom of conscience. Some, like Medina Molera, compare Cervantes to the Moriscos who forged the Lead Books in their search for new literary means of expression. Like other descendants of converts, Cervantes defended human equality against proponents of “pure blood.” Medina Molera even suggests based on genealogical analysis, though this is a minority view that Cervantes may have had Morisco ancestry, which could explain his indirect identification with Islamic ideas and his defense of equality.

Don Quixote is a work of immense richness, whose many layers of interpretation remain relevant today. The themes Cervantes explored including those related to Islam continue to offer valuable insights into contemporary issues. His works contribute to a deeper understanding of Islam, fostering dialogue, understanding, patience, and tolerance toward other cultures. Beyond superficial rhetoric, Cervantes held a modern, European outlook on Islam and freedom of conscience. Interreligious respect shines through, for example, in El gallardo español (“The Gallant Spaniard”), where a Christian and a Muslim part with respectful blessings for each other’s faiths: “May your Muhammad, Ali, protect you” — “May your Christ go with you”.

The information in this article has been taken from Kéri, K. (2005). Cervantes and Islam. Acta Hispanica, 10, 89-103. https://doi.org/10.14232/actahisp.2005.10.89-103

Learn more about the influence of Islam on Spanish literature during the Golden Age on our guided tour “Lives on the border, Moriscos, and literature of the Golden Age in Madrid”.

Cover image: Engraving The Morisco reads Cervantes a few lines from the manuscript © Miguel de Cervantes Virtual Library.

Este artículo está disponible en Español.