Articles

An analysis of wisdom

Even unseasoned readers in the field of History of Philosophy and Science, can easily realize that there have been many ways to search for Wisdom. One might even affirm that, through different periods, some approaches have been considered alternatively wrong and safe. This is a very old and memorable controversy.

When Sócrates proposed to look for truth within the self, starting from the vantage point of not really knowing anything, except the fact that we ignore everything, he tried to suggest a new route of thought equally distant from the so called naturalists and sophists alike. The former had founded, nevertheless, physical, natural and even mathematical sciences, and the latter, dialectic, rhetoric and several other methods to argue and to use language with greater property and exactitude.

However, for a long time, Socrates was considered the philosopher par excellence or, at least, a consistently brilliant mind, triumphantly bellicose against problematic or simply deceptive “received wisdom”. The words “sophistic” and “sophism” have been until very recently loaded with derogatory undertones, although nowadays a more understanding academia re-reads pre-Socratic philosophers more sympathetically (Protagoras, to name but one, is widely recognized as one of the most brilliant minds of his time).

However, for a long time, Socrates was considered the philosopher par excellence or, at least, a consistently brilliant mind, triumphantly bellicose against problematic or simply deceptive “received wisdom”. The words “sophistic” and “sophism” have been until very recently loaded with derogatory undertones, although nowadays a more understanding academia re-reads pre-Socratic philosophers more sympathetically (Protagoras, to name but one, is widely recognized as one of the most brilliant minds of his time).

At any rate, even in our contemporary world, we are still under the impression that there is an almost unattainable Wisdom (with capital letters) out there, and many false or ambiguous “wisdoms” and a certain amount of practical knowledge, which are reached through the study of Science which, unfortunately, leads itself to specialization; that is to say, to a forced limitation, given the amount of effort that must be exercised to master it properly. Science has multiplied into a myriad of sub-disciplines, factual knowledge has become virtually infinite.

So, what is then left for the old Socratic Wisdom, for the man who recognizes that he knows nothing, or at least very little? It is difficult to respond: but evidence indicates that a great deal of people today, even people from radically different cultural backgrounds, still aspire to know something, that elusive “something” not expressed in factual knowledge or specialised scientific data. A nebulous something that is perceived as existing autonomously outside the self, if not against it: frequently, specialised practical knowledge constitutes a source of pride, of excessive self-confidence resulting in a loss of sensitivity when confronting many other serious mundane subjects.

Thus, excess of specialism or premature reductionism notwithstanding, we observe in our days how sciences such as physics and mathematics have been put to the service of war and destruction, perverting theoretically wonderful knowledge into actions utterly repellent to human conscience, as it is the case of scientists experimenting with poor defenseless animals, and even with human beings, as if they were mere objects, lab bait manipulated with absolute disrespect. These “wise” scientists, one could arguably conclude, do not possess any Wisdom at all.

Superior Wisdom

But lets extrapolate our argument to other areas. There are people who try to look for, and take control of, this human, superior Wisdom. In fact, all big organised religions have consistently designed and implemented, from times immemorial, complex systems to achieve it. Buddhism has them, as do Christianity and Islam, in order of historical appearance. There are sects derived from some of these religions that try to assume the governing role in this aspect, like, for example, the Theosophists. The word “Sophia”, wisdom, also appears in other manifold attempts to intellectualise these processes, as in the modern discipline of “Anthropology”.

But lets extrapolate our argument to other areas. There are people who try to look for, and take control of, this human, superior Wisdom. In fact, all big organised religions have consistently designed and implemented, from times immemorial, complex systems to achieve it. Buddhism has them, as do Christianity and Islam, in order of historical appearance. There are sects derived from some of these religions that try to assume the governing role in this aspect, like, for example, the Theosophists. The word “Sophia”, wisdom, also appears in other manifold attempts to intellectualise these processes, as in the modern discipline of “Anthropology”.

But if one concentrates more on the substance than on the etymology, it becomes apparent that there are other less pretentiously verbose attempts to attain the solely desirable knowledge in the end, which is the moral knowledge in its essence, albeit devoid of any spurious element of dogmatic rigidity or exclusive sectarianism.

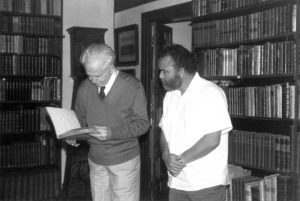

In my old age, it has been a source of joy and comfort, in this world dominated by false wisdoms (or partial wisdoms badly applied), of pride, violence, and aggression, to meet Cherif Abderrahman and his Foundation which, from the starting point of the noblest and most universal principles of Islam, aims to reach that Wisdom that cannot be exclusive, but inclusive of all those men and women who aspire to it, coming from here or there, carrying many diverse cultural baggages, with the ultimate purpose of finding peace and freedom for all.

And freedom also necessarily means knowledge without ties, restrictions or allegiances. This intimate quest, almost individual in its scale, is also my route to Wisdom.

Madrid, the 12th August 1987